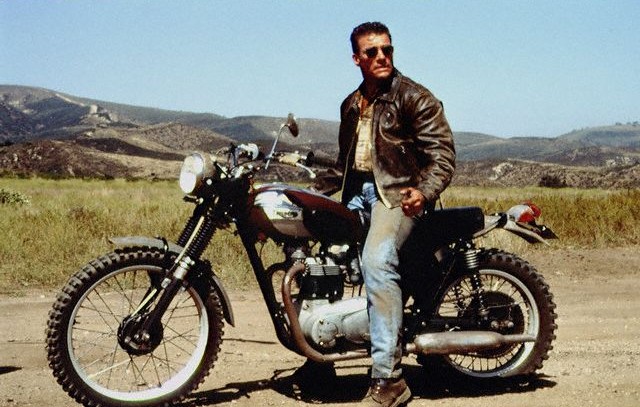

In NOWHERE TO RUN, Jean-Claude Van Damme plays Sam Gillen, a recently escaped convict who finds himself hiding on the outer edges of a rural farm owned by widowed mother Clydie Anderson (Rosanna Arquette) and her two children, Mookie and Bree (Kieran Culkin and Tiffany Taubman). Through a variety of circumstances, Sam learns that a ruthless developer, Franklin Hale (Joss Ackland), and his enforcer Mr. Dunston (Ted Levine), are trying to force all of the farmers to sell their land, using violence if necessary. When bad guys show up one night and threaten Clydie and her kids, Sam emerges from the woods and kicks their asses. Soon Sam finds himself fighting off more of Hale’s goons, romancing the beautiful widow and becoming more emotionally connected to the kids. With his past closing in, Sam decides to do whatever it takes to protect Clydie and her kids, even if that costs him his freedom.

The late 80’s and early 90’s saw the emergence of two new action stars… Steven Seagal and Jean-Claude Van Damme. As a constant patron of our local video stores, I was there at the beginning of their careers and rented each of their new movies as they became available. Van Damme would establish himself in hit films like BLOODSPORT (1988), KICKBOXER (1989), DEATH WARRANT (1990) and UNIVERSAL SOLDIER (1992). As a big fan, I found myself in a movie theater in January of 1993 to watch his latest film, NOWHERE TO RUN.

With a plot that resembles an old western… a man corrupted by wealth tries to force a widow off her land until a kind-hearted drifter steps in… NOWHERE TO RUN isn’t trying to reinvent the action genre, but it does give Van Damme a different kind of role. His Sam Gillen isn’t a wisecracking action hero or an unstoppable martial artist. Rather, he’s a flawed man with a particular set of skills who’s looking for redemption. I think Van Damme plays that soulful weariness better than most would give him credit for. Rosanna Arquette brings a credible presence to this genre film that helps sell the relationship between her and Van Damme, and the presence of her kids, also amps up the stakes and gives the story a genuine sense of vulnerability. When Sam decides to fight back, it’s not to protect himself, but to protect people worth standing up for. That motivation helps make the film more engaging than you might normally expect from an early 90’s action film.

Speaking of action, NOWHERE TO RUN doesn’t feature a ton of action, but what it does have is effective. The early sequence where Van Damme’s character initially steps in to help the terrorized family is especially strong. There are several additional fight sequences and a prolonged motorcycle chase to provide some entertainment, but don’t expect wall-to-wall action or you could be disappointed. Joss Ackland (LETHAL WEAPON 2) and Ted Levine (THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS) are suitably nasty villains so we definitely want to see them get their comeuppances, and the film effectively obliges. I also like the fact that NOWHERE TO RUN is set out on a rural farm. This setting enhances its “western” feel, and I certainly appreciate that unique element for an action film of this era.

At the end of the day, I enjoyed NOWHERE TO RUN when I watched it in the movie theater back in 1993, and I enjoyed it again today. It’s certainly not flashy and action packed like HARD TARGET or TIMECOP, but it is a solid, and surprisingly emotional Van Damme film. I recommend it.