Airport ’77 is the one where the plane ends up underwater.

If the first two Airport movies emphasized the competence of the the crew in both the airplane and the airport, Airport ’77 takes the opposite approach. The first of the Airport films to be released after Watergate, Airport ’77 is a cynical film where no one seems to be particularly good at his or her job. Viewers should be concerned the minute they see that Jack Lemmon is playing Captain Don Gallagher, the pilot of the soon-to-be-submerged airplane. As opposed to Charlton Heston or even the first film’s Dean Martin, Jack Lemmon was always a very emotional actor. He excelled at playing characters who were frustrated with modern life. Just as with Heston and Martin, Lennon plays a pilot who is having an affair with a flight attendant. The big difference is that, this time, the pilot is the one who desperately wants to get married while the flight attendant (played by Brenda Vacarro) is the one who doesn’t want to get tied down. As an actor, Lemmon didn’t have the arrogance of a Heston or the unflappability of Dean Martin. Instead, Jack Lemmon was the epitome of midlife ennui. He’s disillusioned and he’s beaten down. He’s America at the tail end of the 70s.

Another sign that Airport ’77 is a product of the post-Watergate era is the character of co-pilot Bob Chambers (Robert Foxworth). Chambers might seem like a nice and friendly professional but actually, he’s the one who comes up with the plan to knock out all of the passengers with sleeping gas and fly the plane into the Bermuda Triangle so that his partners-in-crime can steal the valuable art works in the cargo hold. Chambers plans is to land the plane on an unchartered isle so that he and Banker (Monte Markham) can make their escape before the rest of the people on the plane even wake up. Instead, Chambers turns out to be as incompetent a pilot as he is a criminal. He crashes the plane into the ocean, where it promptly sinks to the bottom. The impact wakes up the passengers, all of whom can only watch in horror as the ocean envelopes their plane. With the water pressure threatening to crush the plane, Captain Gallagher and engineer Stan Buchek (Darren McGavin) try to figure out how to get everyone to the surface.

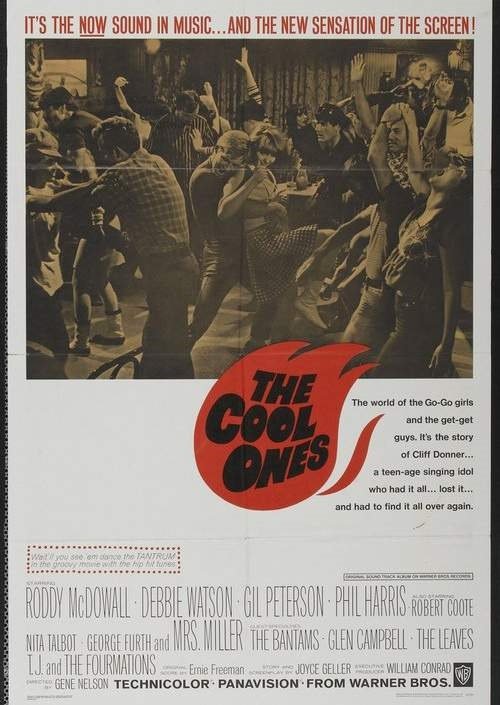

As usual, the passengers are played by a collection of familiar faces. Olivia de Havilland and Joseph Cotten play former lovers who are reunited on the flight. Christopher Lee is a businessman who is unhappily married to alcoholic Lee Grant. Grant is having an affair with Lee’s business partner, Gil Gerard. A young Kathleen Quinlan plays the girlfriend of blind pianist Tom Sullivan. Robert Hooks is the bartender who ends up with a severely broken leg. As the veterinarian who is called to doctor’s duty, M. Emmet Walsh gives the best performance in the film, if just because he’s one of the few characters who really gets to surprise us. Actors like George Furth, Michael Pataki, and Tom Rosqui all wander around in the background, though I dare anyone watching to actually remember the names of the characters that they’re playing. Airport ’77 has the largest number of fatalities of any of the Airport films, largely because even the good guys aren’t really sure about how to reach the surface.

George Kennedy returns as Joe Patroni, though his role is considerably smaller in this film than it was in the first two. He shares most of his scenes with James Stewart, who plays the owner of the plane. Fortunately, neither Stewart nor Kennedy were on the plane when it crashed. Instead, they spend most of the movie in a control room, getting updates about the search. They don’t get to do much in the film but it’s impossible not to smile whenever Jimmy Stewart is onscreen, even if he is noticeably frail.

Airport ’77 is the best-made of all of the Airport films. The crash is well-directed and the scenes of water dripping into the plane are properly ominous. There’s not much depth to the characters but Jack Lemmon and Darren McGavin are likable as the two main heroes and Christopher Lee seems to be enjoying himself in a change-of-pace role. Olivia de Havilland and Joseph Cotten, two old pros, are wonderful together. That said, Airport ’77 is never as much fun as the first two films. Even with the plane underwater, it can’t match the spectacle of Karen Black having to fly a plane until Charlton Heston can be lowered into the cockpit.