“You don’t choose to be a killer, you are chosen.” — The Chancellor

Ballerina lands in theaters feeling like someone finally turned the volume up on the quieter, more balletic side of the John Wick universe. Anchored by Ana de Armas’s poised, ferocious turn, the film doesn’t reinvent the neon‑lit, bullet‑cartoon rules of the franchise so much as rearrange them into a new rhythm. It’s still a very familiar kind of action movie—assassins, codes, bodies on the floor—but it carves out its own niche by centering a woman who’s not just another lethal accessory to John’s world, but someone the world has already trained into a weapon.

At the same time, Ballerina leans hard on the style and flourish of the later John Wick films, and that’s both its main selling point and its biggest limitation. The way shots linger on gun grips, the way the camera circles around bodies mid‑spin, the way every hallway fight feels like stage choreography—it’s all very familiar, very polished, and very much a continuation of the franchise’s visual language. That’s great if you’re here for the aesthetic, but it also means the film sometimes feels more like an extension of the Wick universe’s attitude than a story that confidently stands on its own two feet.

Ana de Armas plays Eve Macarro, a young assassin who grew up in the shadow of the Ruska Roma and the Continental, groomed to kill long before she fully understood what she was doing. The story unfolds in a loose “between films” slot in the Wick timeline, so fans who care about franchise continuity will get their little Easter eggs and cameos, but the film smartly never gets completely bogged down in explaining how this fits into every rulebook. Instead, it leans into the idea that the John Wick universe is big enough that other hunters can walk around in it, following their own grudges and grief. Eve’s motive is straightforward: she wants to track down the people she believes killed her father when she was a child, and along the way she has to square off against both the old guard of her upbringing and the cult‑like killers who seem to operate just outside the established order.

Like a lot of John Wick entries, though, Ballerina is ultimately more interested in expanding the world and reinforcing its rules than drilling deep into its own plot. Eve’s revenge‑driven quest gives the film its spine, but the mechanics of that revenge are often secondary to the chance to show off another assassin enclave, another weird code, or another showdown that feels like a set‑piece first and a character beat second. You can feel the priorities: where she travels, who she bumps into, and how this underworld operates often matter more than whether her arc is especially surprising or emotionally rich. The plotting starts to feel like connective tissue between bigger, more stylized sequences, and that’s where the reliance on franchise style starts to hurt more than help.

The film’s greatest strength is how it employs the language of ballet and violence in the same breath. The title Ballerina might make you expect a lot of literal tutus and pirouettes, and there’s a bit of that in the opening stretches, but the real choreography is in the fight scenes. Eve’s movement is light‑on‑her‑feet one moment—a few spins, a quick sidestep—and then suddenly brutal, close‑quarters savagery the next. The camera doesn’t just document her skills; it dances with them, letting wide‑angle shots show off the architecture of a fight before snapping into tight, impact‑heavy close‑ups. It’s unmistakably a Wick‑style approach, only dialed into a slightly more feminine, almost theatrical register.

De Armas deserves a lot of credit for making Eve feel like a real person, not just a killing machine with a pretty face. She’s cold, yes, but there’s weariness under the surface, the kind that comes from being raised in a world where emotions are a liability. The script doesn’t drown her in backstory; it just lets small moments—a hesitation, a glance at a photo, the way she holds a gun—do the work. When she finally loses her composure and starts to scream, grunt, and visibly struggle during later fights, the effect is more powerful than if she’d been effortlessly killing everyone from minute one. She sweats, she bleeds, she gets thrown around, and that makes her victories feel earned, not just cool.

Stylistically, Ballerina is very much in line with the rest of the franchise: glossy, slightly over‑the‑top, and hyper‑aware of its own aesthetic. The camera work is sleek, the color grading pops, and the score leans into synth textures that feel like a slightly more elegant cousin of the usual Wick pulse. There are also some deliberately playful musical choices—bits of Tchaikovsky and other classical motifs that echo in the background during key scenes—which tie the idea of ballet back to the film’s emotional core. The setting shifts from the familiar New York–style Continental spaces to a quieter, almost fairy‑tale European village that houses a different kind of assassins’ retirement community. It’s a neat trick: the filmmakers give us something that still feels like the same universe but just enough of a different flavor that it doesn’t feel like a rerun.

But that lush style also underlines how much the film is prioritizing world‑building over a tight narrative. Conversations about the Ruska Roma, the Continental, and the cult‑like assassins’ outpost are there less to advance Eve’s inner journey and more to remind us that the John Wick universe is vast, layered, and full of hierarchies. Fans who love the lore will probably eat that up, but if you’re hoping for a more self‑contained narrative, it can start to feel like you’re watching a very expensive lore compendium. The emotional core is there—it just has to fight for space amidst all the visual flexing and mythology maintenance.

Where Ballerina becomes a bit uneven is in its plotting. The basic “one girl, one very long night of revenge” template is solid, but the script doesn’t always give it enough depth or surprise. There are too many conversations where characters explain the rules of the world to each other, or recap what’s already been established, rather than using those moments to add nuance to the characters or relationships. The side figures—like various crime bosses, elders, and reluctant allies—do their jobs entertainingly enough, but they don’t all get the same level of interior life that Eve has. Some of the supporting performances are strong across the board, but the material doesn’t always push them to do anything more than punctuate the action beats.

Keanu Reeves drops in briefly as John Wick, and the cameo is handled with the kind of restraint that makes it feel like a favor rather than a stunt. He doesn’t hang around; he makes a sharp, efficient entrance, has a few quiet exchanges, and then exits, leaving the movie firmly in Eve’s hands. That’s crucial, because one of the criticisms of earlier spin‑off ideas was that they’d feel like vanity detours or glorified cameos. Here, John’s presence actually reinforces the idea that this is someone else’s story now, and that he’s just another player in a much larger ecosystem of killers.

The film’s worst moments are also some of its most visually striking: the bigger, more outlandish set‑pieces that lean fully into the franchise’s “go‑no‑go” action logic. The final third, in particular, is one long, almost goofy crescendo of fights, stunts, and absurdly lethal props. It’s a lot of fun in the moment, but it also underlines how thin the actual plotting can be. When the camera is spinning around a flamethrower‑wielding Eve or a hallway of assassins dropping in from the ceiling, the movie doesn’t always give us enough emotional context to care about who’s living or dying beyond the immediate spectacle. It’s the kind of sequence that will make fans cheer in the theater, but might look a bit clumsier on a second viewing.

One area where Ballerina arguably improves on the core series is its handling of gender dynamics. Eve isn’t fetishized; she’s allowed to be both emotionally grounded and physically dominant without being framed as some kind of fantasy object. The film nods to the idea of “girl power” in the assassin world, but it also lets the character operate within familiar constraints—tradition, hierarchy, and expectation—instead of pretending she’s a one‑woman revolution. She’s tough, but she’s also vulnerable, and that balance keeps the tone from tipping entirely into empty empowerment sloganeering. The way the movie treats her relationships—with her father’s memory, with her mentors, and with the people she’s ordered to kill—adds a layer of emotional sophistication that earlier entries in the franchise often glossed over for the sake of pure momentum.

If you’re coming into Ballerina expecting a radical reinvention of the series, you’ll probably leave a little underwhelmed. It doesn’t rip up the rulebook or deliver a huge thematic twist on what we already know about this universe. Instead, it refocuses the camera on a different kind of protagonist, lets the familiar style breathe a little differently, and proves that the world of John Wick is big enough to house more than just one lone wolf. It’s a stylish, violent, occasionally silly, definitely pulpy action film that knows exactly what it wants to be: a long, bloody ballet in which the lead is a woman who’s finally ready to dance on her own terms—even if the choreography sometimes matters more than the story it’s supposedly telling.

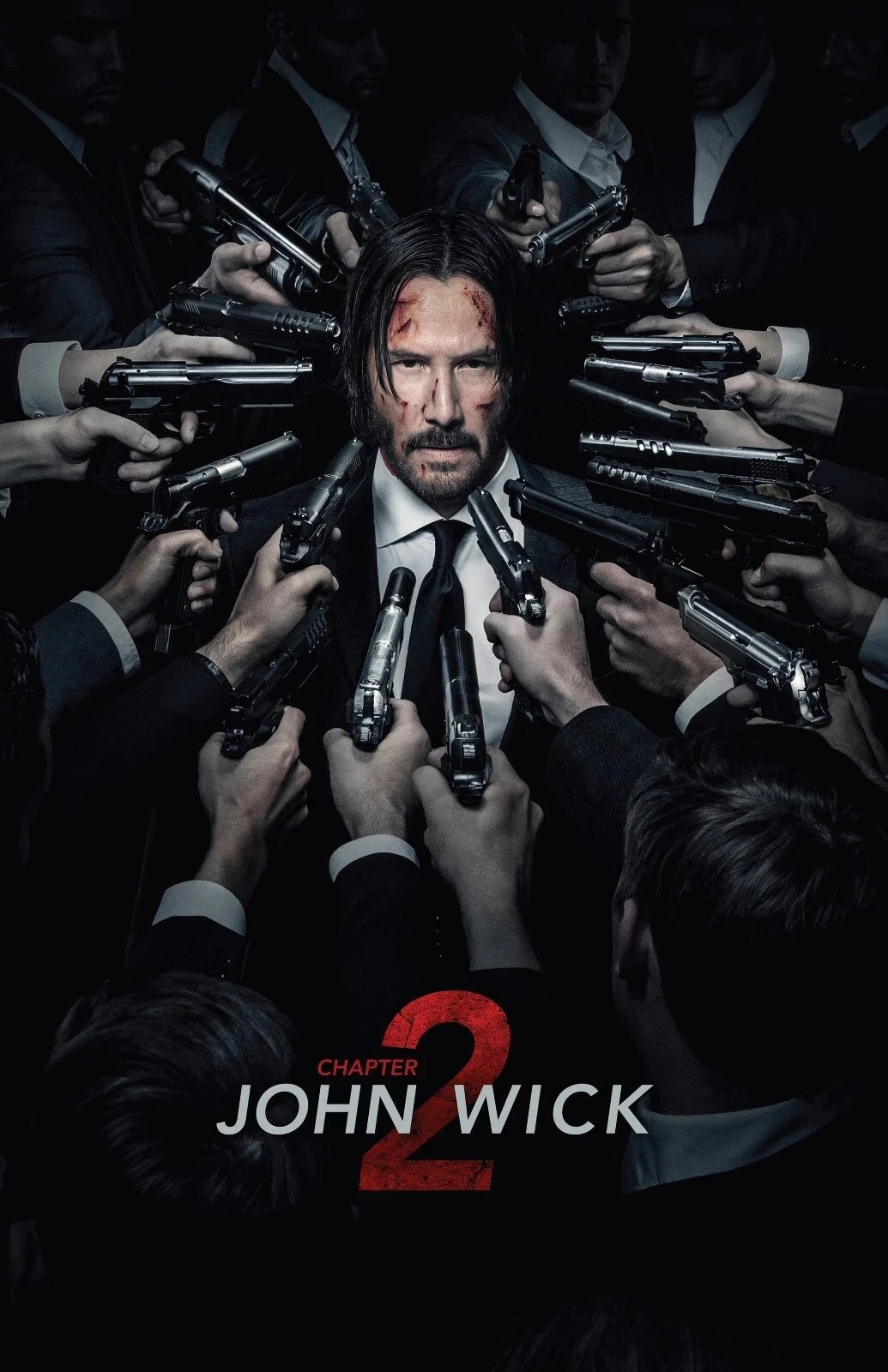

John Wick Franchise (spinoffs)