Ah, the 80s! Ronald Reagan was president. America was strong. Russia was weak. The economy was booming. The music was wonderful. Many great movies were released, though most of them were not nominated for any Oscars. This is the decade that tends to drive most Oscar fanatics batty. So many good films that went unnominated. So many good performers that were overlooked. Let’s dive on in!

1980: The Shining Is Totally Ignored

Admittedly, The Shining was not immediately embraced by critics when it was first released. Stephen King is still whining about the movie and once he went as far as to joke about being happy that he outlived Stanley Kubrick. (Not cool, Steve.) Well, none of that matters. The Shining should have been nominated across the board. “Come and play with us, Danny …. AT THE OSCARS!”

1981: Harrison Ford Is Not Nominated For Best Actor For Raiders of the Lost Ark

Raiders received a lot of nominations. Steven Spielberg was nominated for Best Director. The film itself was nominated for Best Picture. (It lost to Chariots of Fire.) But the man who helped to hold the film together, Harrison Ford, was not nominated for his performance as Indiana Jones. Despite totally changing the way that people looked at archeologists and also making glasses sexy, Harrison Ford was overlooked. I think this was yet another case of the Academy taking a reliable actor for granted.

1982: Brian Dennehy Is Not Nominated For Best Supporting Actor For First Blood

First Blood didn’t receive any Oscar nominations, not even in the technical categories. Personally, I think you could argue that the film, which was much more than just an action film, deserved to be considered for everything from Best Actor to Best Director to Best Picture. But, in the end, if anyone was truly snubbed, it was Brian Dennehy. Dennehy turned Will Teasle into a classic villain. Wisely, neither the film nor Dennehy made the mistake of portraying Sheriff Teasle as being evil. Instead, he was just a very stubborn man who couldn’t admit that he made a mistake in the way he treated John Rambo. Dennehy gave an excellent performance that elevated the entire film.

1984: Once Upon A Time In America Is Totally Ignored

It’s not a huge shock that Once Upon A Time In America didn’t receive any Oscar nominations. Warner Bros. took Sergio Leone’s gangster epic and recut it before giving it a wide release in America. Among other things, scenes were rearranged so that they played out in chronological order, the studio took 90 minutes off of the run time, and the film’s surrealistic and challenging ending was altered. Leone disowned the Warner Bros. edit of the film. Unfortunately, in 1984, most people only saw the edited version of Once Upon A Time In America and Leone was so disillusioned by the experience that he would never direct another film. (That said, even the edited version featured Ennio Morricone’s haunting score, which certainly deserved not just a nomination but also the Oscar.) The original cut of Once Upon A Time In America is one of the greatest gangster films ever made, though one gets the feeling that it might have still been too violent, thematically dark, and narratively complex for the tastes of the Academy in 1984. At a time when the Academy was going out of its way to honor good-for-you films like Gandhi, it’s probable that a film featuring Robert De Niro floating through time in an Opium-induced haze might have been a bridge too far.

1985: The Breakfast Club Is Totally Ignored

Not even a nomination for Best Screenplay! It’s a shame. I’m going to guess that the Academy assumed that The Breakfast Club was just another teen flick. Personally, if nothing else, I would have given the film the Oscar for Best Original Song. Seriously, don’t you forget about me.

1986: Alan Ruck Is Not Nominated For Best Supporting Actor For Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

Poor Cameron!

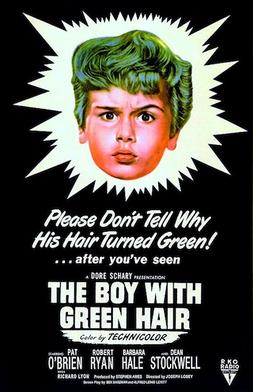

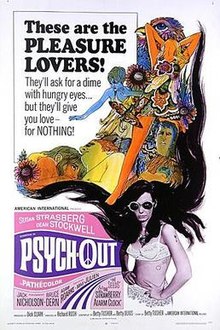

1986: Blue Velvet Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

Considering the type of films that the Academy typically nominated in the 80s, it’s something of a shock that David Lynch even managed to get a Best Director nomination for a film as surreal and subversive as Blue Velvet. Unfortunately, that was the only recognition that the Academy was willing to give to the film. It can also be argued that Kyle MacLachlan, Laura Dern, Isabella Rossellini, and Dean Stockwell were overlooked by the Academy. Dennis Hopper did receive a Supporting Actor nomination in 1986, though it was for Hoosiers and not Blue Velvet.

1987: R. Lee Ermey Is Not Nominated For Best Supporting Actor For Full Metal Jacket

One of the biggest misconceptions about Full Metal Jacket is that R. Lee Ermey was just playing himself. While Ermey was a former drill instructor and he did improvise the majority of his lines (which made him unique among actors who have appeared in Kubrick films), Ermey specifically set out to play Sgt. Hartmann as being a bad drill instructor, one who pushed his recruits too hard, forgot the importance of building them back up, and was so busy being a bully that he failed to notice that Pvt. Pyle had gone off the deep end. Because Ermey was, by most accounts, a good drill instructor, he knew how to portray a bad one and the end result was an award-worthy performance.

1988: Die Hard Is Not Nominated For Best Picture, Actor, Supporting Actor, or Director

Die Hard did receive some technical nominations but, when you consider how influential the film would go on to be, it’s hard not to feel that it deserved more. Almost every action movie villain owes a debt to Alan Rickman’s performance as Hans Gruber. And Bruce Willis …. well, all I can say is that people really took Bruce for granted.

1989: Do The Right Thing Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

Indeed, it would take another 30 years for a film directed by Spike Lee to finally be nominated for Best Picture.

Agree? Disagree? Do you have an Oscar snub that you think is even worse than the 10 listed here? Let us know in the comments!

Up next: It’s the 90s!