(Spoilers Below)

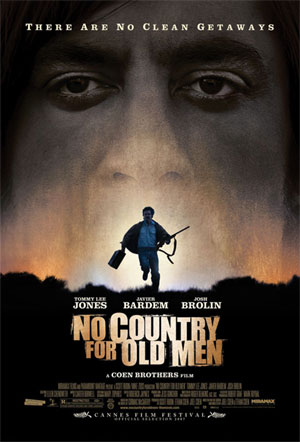

The Counselor was one of the most anticipated films of 2013. After all, it was based on a screenplay by the Pulitzer-prize winning novelist Cormac McCarthy and it was directed by Ridley Scott. Its cast included such stars as Michael Fassbender, Javier Bardem, and Brad Pitt. The film’s two trailers promised a return to the thematic territory that the Coen Brothers explored in their Oscar-winning adaptation of McCarthy’s No Country For Old Men.

And yet, when The Counselor was released in October, the reviews were scathing and audience response was reportedly terrible. Writing for Salon, film “critic” Andrew O’Hehir suggested that The Counselor was not only the worst film of 2013 but the worst film of all time.

And you know what?

For not the first time, Andrew O’Hehir was wrong. The Counselor is not the worst film of 2013. Instead, it’s one of the best. It’s a film that will be studied long after more acclaimed films have been forgotten.

Why is The Counselor so hated?

It’s not an easy film to love. In fact, the film is rather brave about alienating its audience and refusing to allow for the crowd-pleasing moments that viewers have come to expect from even the most prestigious of films.

In order to truly defend the Counselor, it’s necessary to know the plot of The Counselor. Needless to say, everything that follows constitutes a huge spoiler so, if you’re one of those types, feel free to stop reading now.

Okay, still here? Here’s a condensed version of what happens in The Counselor:

The Counselor (Michael Fassbender) is an honest lawyer in El Paso who has never broken the law and is engaged to marry the beautiful and saintly Laura (Penelope Cruz). For reasons that are never explicitly stated (but, as I’ll explain below, are obvious to anyone who is willing to look for the clues), The Counselor agrees to help his clients Westray (Brad Pitt) and Reiner (Javier Bardem) smuggle a huge shipment of cocaine into the U.S. from Mexico. However, Reiner’s girlfriend Malkina (Cameron Diaz) steals the drugs and frames the Counselor for the theft. As a result, Reiner ends up getting executed by the Mexican cartel, Westray is beheaded on the streets of London, and the Counselor ends up hiding out in Juarez, Mexico, sobbing as he looks at a DVD copy of a cartel-produced snuff film that features Laura being murdered. The end.

Yeah, it’s not exactly a happy film. And yet, it’s a film that sticks with you, a portrait of a shadowy underworld that is fueled solely by greed, paranoia, and masculine posturing. Ridley Scott makes good use of the South Texas landscape and the talented cast creates a memorable gallery of rouges.

And yet, The Counselor is getting some of the worst reviews of the year. What’s especially interesting is that the things that so many critic cite as flaws are actually the film’s greatest strengths.

Consider the following common criticisms:

1) The film features some of the most overly articulate drug deals of all time.

This is the most frequent complaint that I’ve come across concerning The Counselor and there is some validity to it. The Counselor is a very talky film. The film’s first hour is pretty much made up of The Counselor having three conversations, all about the same thing and all reaching the same conclusion. Cormac McCarthy’s dialogue is, perhaps not surprisingly, rather portentous and florid. The Counselor does ask the audience to accept a world where even the head of Mexico’s most powerful cartel is given to going off on long philosophical digressions. The Counselor is one of those films where nearly every line seems to have a double meaning.

That said, I think that those who attacking the film’s dialogue are missing the point. This is not meant to be a naturalistic film. Instead, it’s a heavily stylized B-film that uses its sordid story as a metaphor for dealing with deeper issues of greed, masculinity, and the changing mores of American culture. Much as every line of dialogue has a deeper meaning, so does every pulpy plot twist. It takes a while to adjust to McCarthy’s dialogue but, ultimately, that dialogue serves to remind us that the film has a lot more on its mind than just telling the story about a drug deal gone bad. The combination of overly articulate dialogue with primitive violence and desires encourages us to look under the film’s surface.

2) The film’s plot is predictable.

This may be true but I think that’s actually McCarthy’s point. From the start of the film, the Counselor is continually warned that things could potentially go very wrong. Despite these warnings, the Counselor still gets involved in Reiner’s drug and, through a combination of hubris and fate, he loses everything that he loved.

The Counselor’s downfall is not meant to be a surprise. Instead, McCarthy’s point is that the consequences of our actions are usually obvious but we, as human beings, chose to live in denial about just how little control we actually have over our own fate.

3) Ridley Scott’s direction is stylish but ultimately empty.

This argument goes that, while Scott manages to capture some gorgeous images of the Texas/Mexico border, those images ultimately don’t add up to much. The idea goes back to a charge that is frequently leveled against Ridley Scott as a director, that he’s all style and technique with little substance. (Interestingly enough, this is the same charge that is often made against the Coen Brothers.)

In the past, I’ve been critical of Ridley Scott. (For proof, check out my reviews of Robin Hood and Gladiator.) However, that being said, I think that, with The Counselor, Scott does a good job of visually interpreting the concepts at the heart of McCarthy’s script. My mom was from South Texas and I’ve spent enough time down there to understand just how perfectly Ridley Scott manages to capture the combination of beauty and harshness that one finds along the border between Texas and Mexico. In Scott’s hands, the emptiness of the Texas landscape serves as a perfect parallel for the emptiness of the lives of the majority of the film’s characters.

Speaking of which…

4) The motivations of the Counselor remain a mystery.

Why does the Counselor get involved in the drug deal in the first place? Many of the film’s critics have complained that the Counselor’s motivations remains a mystery and therefore make it impossible for audiences to sympathize with the character.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

What these critics are failing to realize is that the Counselor’s motives are obvious every time that he appears on-screen. The audience has to be willing to look for them. The audience has to be willing to think and that, of course, is asking quite a bit of some viewers.

While the Counselor hints that his reason for getting involved with the drug deal is so that he can make enough money to provide a good life for Laura, his actual motivations are far more selfish. One need only see the Counselor in his perfectly pressed suits or in his sleek but sterile home to understand exactly who the Counselor is. He is a character who has made his living by defending those who break the law but who has never had the courage to actually flaunt the rules himself. He is a man who lives in a self-constructed prison of ennui and associating with Reiner and Westray gives him a chance to escape from his conventional existence. He is a character who spends his day profiting from the crimes of others but, because he can go home to his beautiful home and his beautiful fiancee, assumes that he’s somehow detached from the consequences of the actions of his associates.

The Counselor starts the film as an unemotional, blank-faced cipher, a man whose entire identity is based on his job title. (Indeed, we never learn once learn or hear the character’s actual name.) The only time that he shows even a hint of human depth or emotion is when he’s with Laura. He’s a man who, in many ways, is dead on the inside. It’s only after he gets involved with Reiner and Westray that the Counselor starts to show any signs of life until, by the end of the film, he literally cannot control his emotions. The Counselor frees himself from his stifling and conventional existence at the cost of everything and everybody that he loves. In his pursuit of freedom, he simply moves from one self-imposed prison to another.

5) Particularly in its portrayal of Malkina, there is a strong streak of misogyny running through the film.

This is a point that I’ve seen made by several critics and it’s one that bothers me as both a feminist and as a female who happens to love genre films. Just because a film features a misogynistic character does that therefore make the film itself misogynistic?

The majority of those who claim that The Counselor is anti-female often point to the character of Malkina. As played by Cameron Diaz, Malkina is a hyper sexual sociopath who manipulates and destroys everyone else in the film. Even though he’s obsessed with her, Reiner also claims to fear her and he has several conversations with the Counselor in which he cites her as proof that women cannot be trusted.

However, just because Reiner says this, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the film agrees. In fact, as should be obvious to anyone who is actually willing to pay attention to the film, Reiner is portrayed as being a fool who, ultimately, is just as delusional as the Counselor. Reiner, Wainstray, and the Counselor all exist in a hyper masculine environment. For all of their posturing and macho talk, it’s also obvious that none of them are capable of truly dealing with women. Wainstray can only bring himself to acknowledge them as potential sexual partners while the Counselor both idealizes Laura and uses her happiness as an excuse to pursue his own criminal enterprises. Reiner, meanwhile, is both attracted to and terrified of Malkina.

In perhaps the film’s most infamous scene, Malkina removes her panties and then grinds against the windshield of a Ferrari while Reiner watches from inside the car. Some have argued that, with this scene, the filmmakers are equating Malkina’s sexuality with evil. I, however, would argue that this scene shows that Malkina — alone of all the film’s major characters — understands the fact that all of the men in her life are essentially boys who are either incapable of or unwilling to grow up. Malkina uses her sexuality not because she’s evil but because she’s intelligent enough to use every weapon at her disposal to make sure that she will be one of the few characters to survive to the movie’s conclusion. By the end of the film, it’s obvious that Malkina is both the strongest and the most intelligent character in the film.

There’s an interesting scene towards the end of the film in which the Counselor, who is hiding out in Juarez, stumbles across a group of protesters who are holding pictures of young women who have either been killed on or vanished from the streets of Juarez. Since 1993, over 4000 women have been murdered in Juarez. The majority of those murders are still unsolved, with many blaming the Spanish tradition of machismo. The feeling of many is that “good” girls stay home while “bad” girls get jobs in the city and are often murdered as a result. And, since the victims shouldn’t have been pursuing a life outside of domestic servitude in the first place, why waste the time trying to win them any sort of justice? For the past decade, brave activists have put themselves in danger by daring to demand justice for the dead of Juarez. When the Counselor stumbles across their rally, it’s a brief moment in which the real world and the cinematic landscape come together.

It’s also a scene that serves to remind us that the film’s characters are living in a hyper masculine world, one that embraces the concept of machismo without understanding or caring about the consequences of that destructive culture. The Counselor’s horrified reaction to the rally is the reaction of a man who has finally been forced to confront the evil of which he is now a permanent part.

6) The film’s ending is depressing.

Complaining about Cormac McCarthy writing a depressing ending is a bit like getting upset at a cat for purring. It’s what McCarthy does and anyone with any knowledge of his work has no right to be shocked that the film ends on a note of hopelessness. Much as with No Country For Old Men, The Counselor ends the only way that it can. It may not be a happy ending but it is, at least, an honest ending.

The Counselor may not be an easy film to like but it’s definitely a film that deserves better than to be dismissed as the worst of 2013.