In 1979’s The Concorde …. Airport ’79, Joe Patroni (George Kennedy) finally gets to fly the plane.

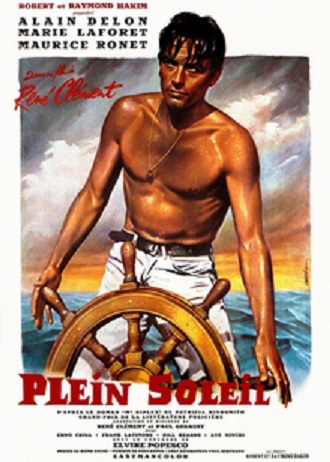

The plane is question is a Concorde, a supersonic airliner that can travel faster than the speed of sound. When we first see the Concorde, it’s narrowly avoiding a bunch of dumbass hippies in a hot air balloon as it lands in Washington, D.C. The recently widowed Joe Patroni joins a flight crew that includes neurotic Peter O’Neill (David Warner), who says that he has dreams in which he’s eaten by a banana, and suave co-pilot Paul Metrand (Alain Delon). Because this is an Airport film, Mertrand is dating the head flight attendant, Isabelle (Syliva Kristel). “You pilots are such men,” Isabelle says. “It ain’t called a cockpit for nothing, honey,” Patroni replies.

(One thing that is not explained is just how exactly Joe Patroni has gone from being a chief technician in the first film to an airline executive in the second to a “liaison” in the third and finally to a pilot in the fourth.)

The Concorde is flying to Moscow with a stop-over in Paris. There’s the usual collection of passengers, all of whom have their own barely-explored dramas. Cicely Tyson plays a woman who is transporting a heart for a transplant. She gets maybe four or five lines. Eddie Albert is the owner of the airline and he’s traveling with his fourth wife. (Of course, he’s old friends with Patroni.) John Davidson is an American reporter who is in love with a Russian gymnast (Andrea Marcovicci). Avery Schrieber is traveling with his deaf daughter. Monica Lewis plays a former jazz great who will be performing at the Moscow Jazz Festival. Jimmie Walker is her weed-smoking saxophonist. Charo shows up as herself and gets kicked off the plane before it takes off.

The most important of the passengers is Maggie Whelan (Susan Blakely), a journalist who has evidence that her boyfriend, Kevin Harrison (Robert Wagner), is an arms trafficker. Harrison is determined to prevent that evidence from being released so he programs a surface-to-air missile to chase the Concorde. Patroni is able to do some swift maneuvers in order to avoid the missile, which means that we get multiple shots of passengers being tossed forward, backwards, and occasionally hanging upside down as Patroni flips over the plane. Oddly no one really gets upset at Patroni about any of this and no one seems to be terribly worried about the fact that someone is obviously trying blow up their plane. Even after the stop-over in Paris, everyone gets back on the Concorde! That includes Maggie, who could have saved everyone a lot of trouble by just holding a press conference as soon as the plane landed in Paris.

A year after The Concorde came out, Airplane! pretty much ended the disaster genre. However, even if Airplane! had never been released, I imagine The Concorde would have still been the final Airport film. Everything about the film feels like the end of the line, from the terrible special effects to the nonsensical script to the Charo cameo and Martha Raye’s performance as a passenger with a weak bladder. The first Airport film was an old-fashioned studio film standing defiant against the “New Hollywood.” The second Airport film was a camp spectacular. The third Airport film was an example of changing times. The fourth Airport film is just silly.

And, really, that’s the main pleasure to be found in The Concorde. It’s such an overwhelmingly silly film that it’s hard to look away from it. For all of its weaknesses, The Concorde will always be remembered as the film that featured George Kennedy opening the cockpit window — while in flight — and shooting a flare gun at another plane. As crazy as that scene is, just wait for the follow-up where Kennedy accidentally fires a second flare in the cockpit. “Put that out,” Alain Delon says while David Warner grabs a fire extinguisher. It’s a silly moment that it also, in its way, a great moment.

The Concorde brings the Airport franchise to a close. At least George Kennedy finally got to fly a plane.