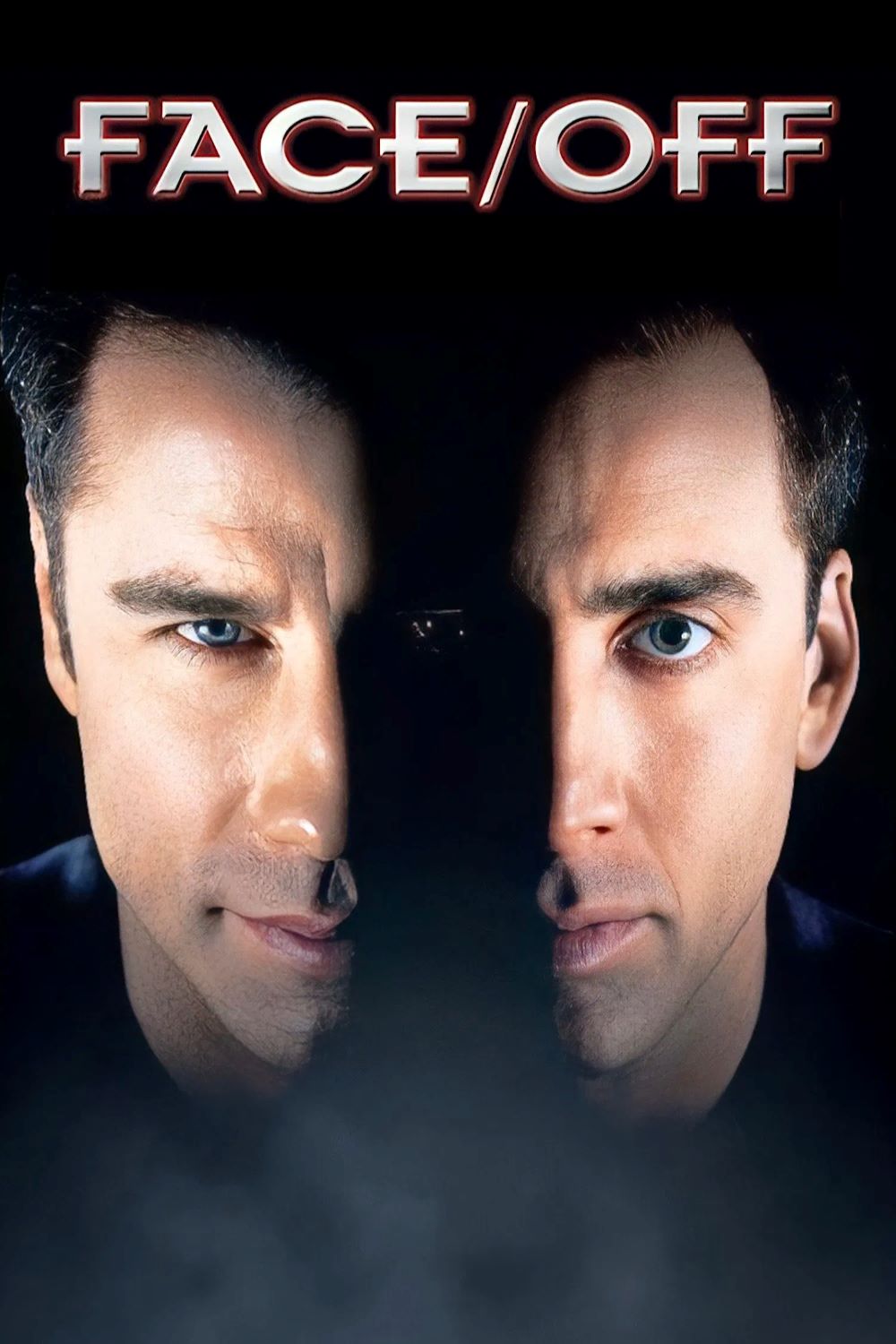

“It’s like looking in a mirror. Only… Not.” — Castor Troy with Sean Archer’s face

Face/Off is one of those late‑90s action movies that feels like it escaped from an alternate universe where “too much” is a compliment, not a warning label. It is bigger than it needs to be, sillier than the premise probably deserves, and yet somehow more emotionally earnest than most modern blockbusters. The result is a film that swings hard between breathtakingly good and gloriously ridiculous, and that tension is exactly what makes it worth revisiting.

At its core, Face/Off is a story about two men who literally become each other, but it works because it never treats that concept as a small thing. John Travolta’s Sean Archer is an FBI agent consumed by grief after the death of his young son, while Nicolas Cage’s Castor Troy is a theatrical terrorist who seems to enjoy being evil as a kind of performance art. The sci‑fi hook—cutting off their faces and swapping them—does not remotely pass a reality test, but the movie leans into the idea with such conviction that you either roll with it or get left behind in the opening act.

The big selling point is the acting showcase baked into that swap. Watching Travolta play a supposedly buttoned‑up lawman unraveling inside the body of a flamboyant villain, while Cage dials his madness into something deceptively controlled, gives the film a strange, theatrical energy. There is a real pleasure in tracking how each actor steals little gestures and rhythms from the other, so scenes become layered: what you’re seeing on the surface and who you know is “underneath” the borrowed face are constantly at odds.

That identity confusion isn’t just a gimmick; it gives the film some surprising emotional weight. Archer’s grief isn’t window dressing—his obsession with bringing down Troy comes from the trauma of losing his son, and the face swap forces him to confront who he’s become in that tunnel‑vision pursuit. Meanwhile, Troy, once inside Archer’s life, plays “family man” in a way that’s both gross and unnervingly intimate, manipulating Archer’s wife Eve and daughter Jamie with a mix of faux tenderness and predatory charm.

Joan Allen, as Eve, quietly grounds all this insanity. Her character spends a good chunk of the film being gaslit on a level that would break most people, yet Allen plays her with a subdued intelligence that makes the eventual moment of realization feel earned instead of convenient. Dominique Swain’s Jamie gets more of a stock “rebellious teen” setup, but the way Troy‑as‑Archer slithers into her life gives some scenes a genuinely uncomfortable edge, underlining how invasive the villain’s masquerade really is.

Of course, this is a John Woo movie, so the drama is constantly fighting for space with balletic gunfights and slow‑motion chaos. The action is elaborate and stylized, full of dual pistols, flying bodies, and highly choreographed carnage that feels closer to a violent dance than a grounded firefight. Whether it is the prison escape with its magnetic boots or the church shootout framed with doves and religious imagery, Woo stages set pieces as big operatic crescendos, not just plot checkpoints.

That operatic tone is both a strength and a weakness. On the one hand, the heightened style matches the bonkers premise, letting the movie exist in a kind of hyper‑reality where emotions and bullets fly with the same intensity. On the other hand, the sheer excess sometimes undercuts the more serious beats, as if the film can’t decide whether it wants to be a heartfelt story about grief and identity or the wildest action comic you have ever flipped through.

The script occasionally gestures at deeper themes but rarely lingers on them. Archer’s time in a secret off‑the‑books prison hints at broader commentary about state power and dehumanization, yet the movie mostly uses the setting as a backdrop for an escape sequence rather than exploring what it means. Similarly, Troy’s infiltration of Archer’s family brushes against ideas about how easily trust and intimacy can be weaponized, but the story is more interested in cranking up tension than really unpacking that psychological damage.

Where the writing truly shines is in the mechanics of the cat‑and‑mouse relationship. The film keeps finding new ways to twist the knife, whether it’s Archer stuck in Troy’s body trying to convince former enemies he’s changed sides, or Troy using Archer’s authority to erase evidence and tighten the trap. Some of the most satisfying scenes are the quieter confrontations where both men have to stay in character in front of others while aiming verbal daggers at each other, maintaining the illusion even as their hatred escalates.

Still, Face/Off is not exactly a model of restraint or logic, and that’s where some fair criticism comes in. The science of the face swap is nonsense even by sci‑fi standards, and the movie’s attempts to hand‑wave voice, body shape, and mannerisms require a level of suspension of disbelief that will be deal‑breaking for some viewers. On top of that, the third act piles on so many stunts and reversals that fatigue can set in; not every action beat feels necessary when the emotional arc has already hit its key notes.

There is also the question of tone in how the film treats violence and trauma. The opening murder of Archer’s son is genuinely brutal, and the later manipulation of his family taps into real discomfort, yet the movie often snaps back into cool‑shot mode a moment later, as if unsure how long it wants to sit with pain. That tonal whiplash can make it hard to fully buy into the emotional stakes, because the film keeps reminding you it is here, first and foremost, to put on a show.

Despite those flaws, Face/Off has aged in a strangely resilient way. In an era where many big action movies flatten actors into interchangeable cogs in a CG machine, there’s something refreshing about how much personality this film allows its leads to display, even when they’re chewing the scenery. The movie’s excess becomes part of its charm: it feels handcrafted in its madness, a spectacle built around big performances rather than just big effects.

Face/Off is neither a straightforward masterpiece nor a disposable guilty pleasure; it lives in a messy, entertaining space between those extremes. The film delivers memorable performances, inventive set pieces, and a surprisingly sincere emotional throughline, but it also leans on ludicrous science, tonal inconsistency, and overindulgent action. If you can accept its central absurdity and meet it on its own heightened wavelength, it remains a wild, engaging ride that showcases what happens when star power, genre bravado, and unfiltered style crash into each other at full speed.