“What is sacred to a bunch of goddamned savages ain’t no concern of the civilized man! We got permission!” — Buddy

Bone Tomahawk (2015) begins in quiet dread. A still horizon, the whisper of wind across rock, a hint of bone under the dust—the American frontier looms like an unfinished thought. This silence sets the tone for S. Craig Zahler’s remarkable debut, a film that wears the form of a Western only to strip it down to nerve and marrow. It’s a story of decency under siege, of men pushing past the last borders of civilization and discovering that what lies beyond is not the unknown, but the origin of everything they thought they’d overcome.

At first glance, the premise seems familiar. When several townspeople vanish from the small settlement of Bright Hope, Sheriff Franklin Hunt (Kurt Russell) leads a rescue expedition into the desert. Riding with him are three others: the injured but determined Arthur O’Dwyer (Patrick Wilson), whose wife has been taken; his tender-hearted deputy, Chicory (Richard Jenkins), whose chatter and old-fashioned kindness soften the film’s bleak austerity; and the self-assured gunman John Brooder (Matthew Fox), a man equal parts gallant and cruel. Together, they represent the moral cross-section of a civilization still trying to define itself—duty, love, loyalty, arrogance.

Their journey outward becomes one of inward descent. Zahler’s script unfolds at a deliberate pace, steeped in stillness and exhaustion. The first half moves like ritual—meandering conversations, humor worn thin by weariness, the small comforts of campfire fellowship flickering against the vast emptiness around them. It’s here that Bone Tomahawk begins its slow transformation. What starts as a rescue Western gradually becomes something deeper and older. By stripping away the romance of exploration, Zahler reveals the frontier not as a space of discovery, but as a place of reckoning—a mirror of the instincts civilization pretends to have tamed.

The film’s most haunting element is its portrayal of the so-called “troglodytes,” the mysterious group believed to be responsible for the kidnappings. They are less a tribe than an incarnation of the wilderness itself—nameless, wordless, and utterly beyond cultural translation. Covered in ash, communicating through the eerie hum of bone instruments embedded in their throats, they seem less human than ancestral, as though the land itself had dragged them upward from its own depths. Zahler refuses to frame them anthropologically or politically; instead, they represent the primal truth the American frontier sought to bury under its myths of order and progress.

Western films, for more than a century, have mythologized the wilderness as an external force—something to conquer. But the “troglodytes” in Bone Tomahawk feel like the soil’s memory of what came before conquest: the savage necessity that built the very myths used to conceal it. They are the frontier’s unspoken ancestry—what remains after all the churches, taverns, and codes of decency are stripped away. Civilization needs them to remain hidden in the canyons, out of sight and unspoken, because their existence contradicts everything the polite narrative of the Old West stands for. They are what progress denies but cannot erase.

Zahler’s restraint strengthens this allegory. He shoots the desert not as backdrop but as evidence—a geographical wound extending beyond the horizon. The wilderness looks stunning but predatory, its stillness full of threat. Even when the posse’s odyssey is free of immediate danger, there’s the growing sense of being consumed: by the sun, by exhaustion, by the quiet knowledge that the world they’re riding into has no use for their notions of law and virtue. Civilization, here, is a pocket of light surrounded by something much older and hungrier.

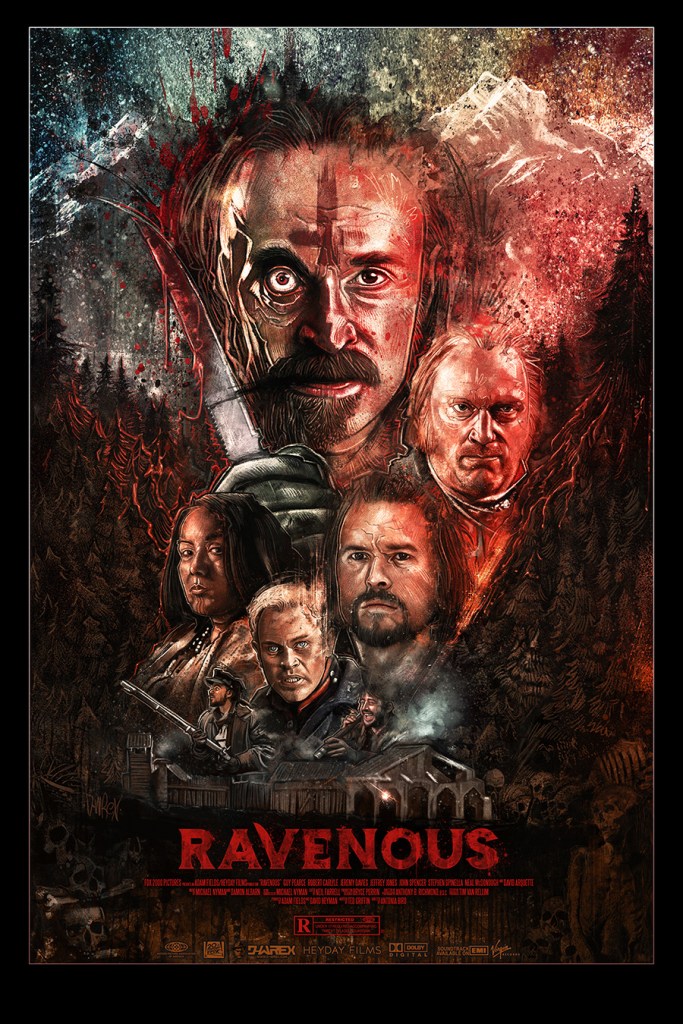

That hunger, the need to conquer and consume, connects Bone Tomahawk to its spiritual predecessor, Antonia Bird’s Ravenous (1999). Bird’s film transformed the Donner Party’s historical ghosts into an allegory of Manifest Destiny, equating cannibalism with American expansion—the act of devouring land, life, and self under the guise of progress. Zahler continues that lineage with deliberate starkness. For him, violence in the frontier isn’t just literal; it’s foundational, the unacknowledged currency of civilization. Where Ravenous expressed its critique with mordant humor, Bone Tomahawk speaks in solemn tones, observing how every civilized act—the enforcement of law, the defense of home—rests upon the refusal to see what was consumed to create it.

The “troglodytes” embody that refusal incarnate. They are not villains in the traditional sense; Zahler grants them no ideology or explanation, only the primal fact of their survival. In doing so, he flips the Western’s moral equation: the barbarians at the edge of civilization are not invaders, but reminders of its origins. They are ghosts of the violence that founded the frontier, the unspoken proof that the West was never as far from savagery as it claimed. To look upon them is to glimpse the beginning—the raw, lawless reality America buried beneath the idea of itself.

Kurt Russell, magnificent in his restraint, anchors this tension. His Sheriff Hunt evokes a fading kind of decency: measured, fair, and unwavering even in futility. Russell plays him not as a Western hero but as a man committed to honor in a world that no longer rewards it. His calm authority softens only around those he loves and hardens in the face of what he doesn’t understand. In that measured decency lies the film’s aching question: what happens when morality meets something that does not recognize it?

Patrick Wilson’s O’Dwyer embodies faith’s physical agony—a man driven by devotion, limping through a landscape that punishes his determination. Richard Jenkins provides heart and subtle tragedy; his rambling, almost comical musings on aging and loneliness become the story’s moral texture, the sound of humanity scraping against extinction. And Matthew Fox, in his most precise performance, gives voice to the arrogance of the civilized killer—a man who fashions violence as virtue, believing his elegance excuses his cruelty.

Together, the four men form a living cross-section of the West’s moral mythos. Their journey exposes how fragile those ideals become once separated from the safety of town limits. They embody the dream of order confronting the truth of chaos—and the cost of looking too long into the void beyond it.

Zahler’s filmmaking is remarkably self-assured for a debut, and what stands out most is his willingness to trust stillness. There is no manipulated rhythm, no swelling score to guide emotion. The soundscape is shaped by wind, hoofbeats, crackling fires, and quiet voices rattled by exhaustion. The silence itself becomes a spiritual presence, pressing down on the travelers until conversation feels like resistance. Each scene builds tension not through action, but through waiting—the dread of what remains unseen, what civilization has pretended not to hear.

The violence, when it erupts, is unforgettable. Zahler does not linger voyeuristically, yet the weight of what happens lands with moral precision. The horror feels earned—an eruption of the primal into the civilized. Its purpose is not to shock, but to remind: the line between the men of Bright Hope and the people they fear is thinner than they want to believe. The frontier, as Zahler presents it, is not an untouched wilderness but the graveyard of an ongoing denial—the myth of progress stacked atop the bones of the devoured.

In that way, Bone Tomahawk moves beyond the idea of genre blending. It is not merely a “horror Western,” but a meditation on how those two sensibilities spring from the same source. Both depend on the confrontation between safety and the unknown, belief and disbelief. Both are rituals of fear, structured to reassure yet always at risk of unveiling the truth. Zahler’s greatest achievement is the way he strips away that reassurance. By the film’s final stretch, the promises of civilization—hope, faith, righteousness—have been exposed as fragile constructions built atop an ancient void.

And yet, through all its darkness, Zahler allows a flicker of grace. The film’s humanity endures in small gestures: a conversation interrupted by laughter, a hand extended in kindness, the stubborn persistence of dignity in impossible circumstances. Bone Tomahawk never preaches or offers catharsis, but it does something harder—it bears witness. It shows men maintaining decency not because it protects them, but because it defines them. In that endurance lies the film’s quiet heartbeat.

Like Ravenous before it, Bone Tomahawk reimagines cannibalism and frontier brutality not as aberrations, but as mirrors reflecting a truth about the American project: that every step westward demanded erasure, and that what was erased refuses to stay buried. The “troglodytes” linger not only in the canyons but within the culture that feared them—proof that civilization’s polish has always covered the rough, enduring shape of appetite.

By the end, what remains is not revelation or redemption, but silence—the kind that comes after myth collapses. Zahler’s film leaves its characters and viewers alike to confront the space where civilization ends and something older begins. The desert remains untouched, vast and timeless, holding the secret at the center of all Western stories: that progress has always been haunted by the primitive, that the world we built never left the wilderness—it merely disguised it.

Measured, brutal, and strangely tender, Bone Tomahawk stands as both a reclamation and an undoing of the Western myth. It listens to the echoes of the Old West and answers them not with triumph, but with reckoning. In its dust and silence lies a truth older than law or legend: civilization may light its fires, but there will always be something in the dark watching, waiting—the part of us it never truly left behind.