Gary Cooper. Joan Fontaine, Mary Astor, and Donald Crisp at the 1942 Oscars.

Continuing our look at good films that were not nominated for best picture, here are 6 films from the 1940s.

Shadow of a Doubt (1943, dir by Alfred Hitchcock)

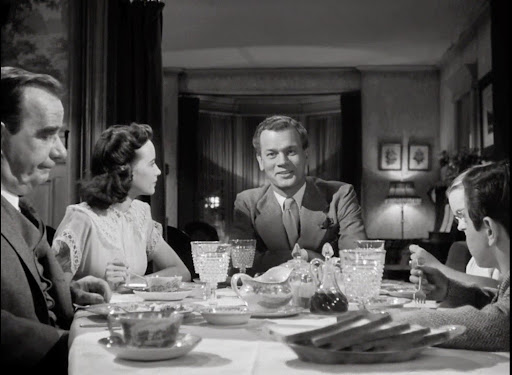

Amazing, Alfred Hitchcock never won the Best Directing Oscar. In fact, it was rare that his films were even nominated. (Though Rebecca did win Best Picture, it could be argued that film’s style was as much to due to David O. Selznick as it was to Hitchcock.) One of the best of Hitchcock’s unnominated films was Shadow of a Doubt. With its dark sense of humor and wonderful performances from Joseph Cotten and Teresa Wright, Shadow of a Doubt was Hitchcock at his best. It was also, perhaps, a bit too darkly subversive for the Academy.

Detour (1945, dir by Edgar G. Ulmer)

The ultimate film noir nightmare, Detour was actually well-received when it was originally released, though it would take a while for the film to be recognized as a true classic. Still, there was no way that the Academy was going to nominate a low-budget B-movie about a guy who hitchhikes across America and manages to accidentally kill two people. Detour was far too nightmarish and surreal for the Academy but it’s remained one of the most influential films ever made.

Gilda (1946, dir by Charles Vidor)

Another classic film noir, Gilda is the film that, for many, will always define Rita Hayworth. Through the film was a financial and critical success, it was ignored by the Academy. The success of this film and the popularity of Hayworth’s performance led to the fourth atomic bomb to ever be detonated being named Gilda. Rita Hayworth was reportedly not happy to hear it.

Black Narcissus (1947, dir by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger)

One of the most visually stunning films ever made, Black Narcissus won Oscars for Best Cinematography and for Art Design but it received no other nominations, not even for the outstanding performances of Deborah Kerr and Kathleen Byron, as two nuns who have very different reactions to the Himalayas.

Out of the Past (1947, dir by Jacques Tourneur)

A world-weary private investigator (Robert Michum) is hired by a slick and psychotic gangster (Kirk Douglas) and ordered to track down the gangster’s girlfriend (Jane Greer). So beings this rather melancholy and introspective film noir, one that is distinguished by wonderfully shadowy photography and which features one of Mitchum’s best performances. Sadly, the Academy recognized neither the film nor Mitchum’s performance.

Portrait of Jennie (1948, dir by William Dieterle)

This haunting and dream-like fantasy stars Joseph Cotten as a painter who meets, paints, and falls in love with a mysterious woman (Jennifer Jones) who may not be what she seems. The film was apparently not a huge success when it was first released but, seen today, it’s hard not to get swept up in the film’s romantic sadness. Though it received a nomination for Best Cinematography, it was otherwise ignored by the Academy.

Up next, in about an hour or so, the 1950s!