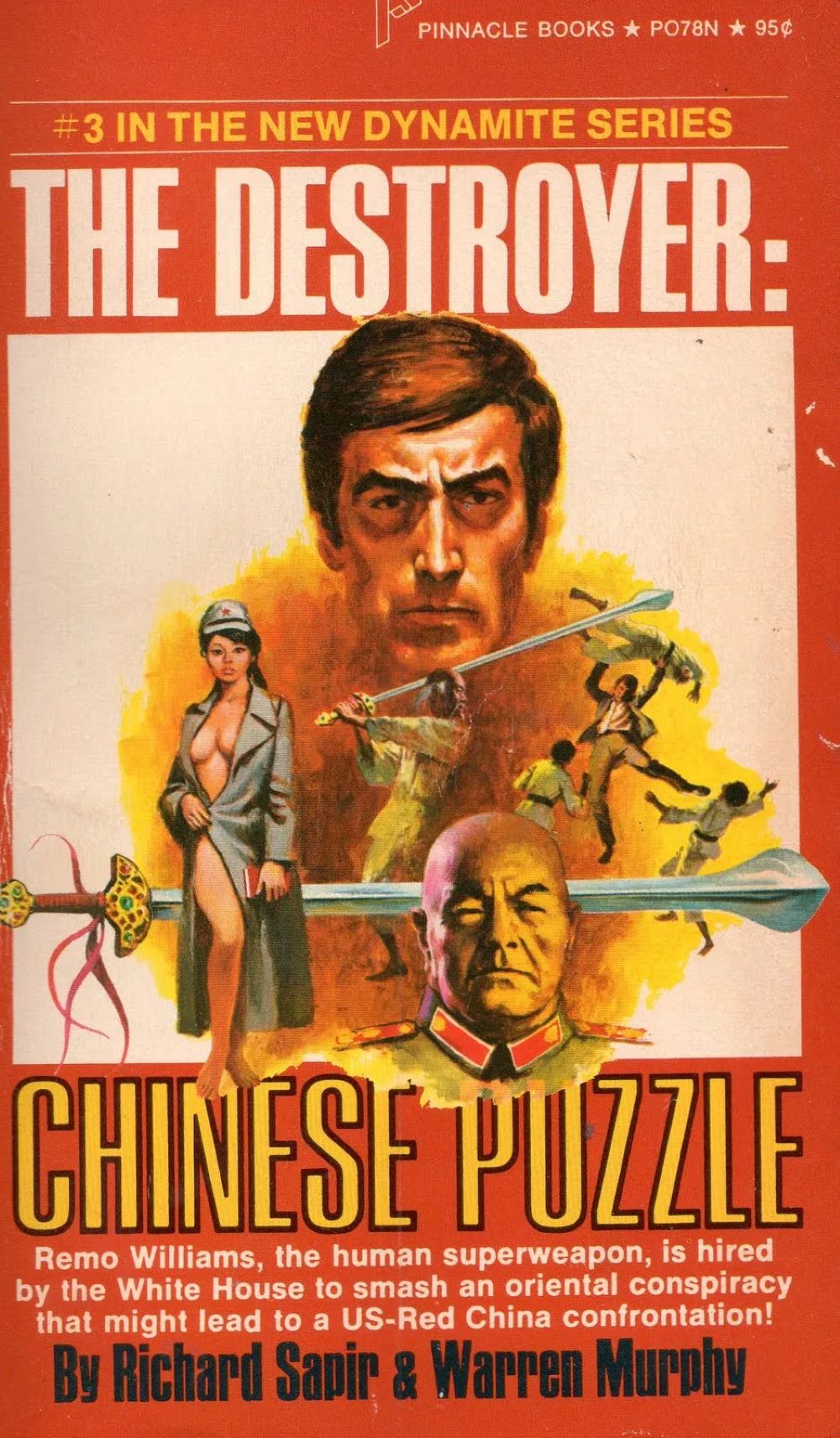

The Destroyer series, launched in 1971 by Warren Murphy and Richard Sapir and later chiefly associated with Murphy, is the kind of long‑running action franchise that practically defines “guilty pleasure.” Spanning more than 150 paperback entries and various continuations, it rarely pretends to be anything other than what it is: fast, frequently outrageous pulp about a government assassin and his irascible Korean mentor saving the world by killing people who, in the moral logic of the series, really need killing.

At the center is Remo Williams, a former Newark cop framed for murder, executed on death row, and then quietly “resurrected” to become the enforcement arm for a secret U.S. organization called CURE. The first novel, Created, The Destroyer, uses this grim premise almost as a prologue; the series is far less interested in legal nuance than in setting up a clean break from Remo’s past so he can be remade as a weapon. His new life is one of deniability and isolation, and the books lean into that fantasy of the invisible man behind the headlines, quietly eliminating threats that conventional systems can’t touch. It’s not realistic, and it isn’t trying to be; the appeal lies in how cheerfully the series weaponizes that premise for brisk, punchy adventure.

The real hook, though, is Remo’s training in the Korean assassination art of Sinanju, and his relationship with its current master, Chiun. Chiun, drawn from a secretive village of assassins who have supposedly served emperors and leaders for millennia, turns the usual mentor trope into a running act of ethnic, generational, and cultural clash. He’s vain, mercenary, and spectacularly contemptuous of Americans, and a lot of the series’ humor comes from his withering commentary on U.S. culture, politics, and Remo’s stubbornly ordinary tastes. Remo calls him “Little Father,” and as the books go on, the bickering most often reads like a truly dysfunctional but oddly affectionate family argument played against a backdrop of exploding supervillain lairs. That dynamic is where the series unexpectedly finds a core of warmth amid all the cartoon violence.

On the action front, The Destroyer exists squarely in the men’s adventure boom of the 1970s, alongside series like Don Pendleton’s The Executioner, but evolves into something stranger and more openly satirical. Early on, Remo’s feats are at least vaguely grounded in martial arts exaggeration, but as the volumes pile up, Sinanju becomes almost superheroic: running up walls, shredding steel, and dispatching opponents with fingertips and casual nose‑ripping brutality. The series’ foes range from mobsters to mad scientists, corrupt officials, rogue militaries, and outright parodies of real‑world figures, and the books gleefully mix crime fiction with borderline science fiction and spy‑thriller gadgets. A lot of the fun is in watching Murphy escalate the stakes from book to book, then resolving everything with hands‑on mayhem because Sinanju doctrine disdains guns as spiritually unclean. When it clicks, it has the energy of a comic book written in pure pulp prose.

What keeps The Destroyer from feeling like just another relic of that boom is its tonal tightrope walk between earnest action and broad satire. CURE itself, the secret agency that “does not exist,” is a kind of bureaucratic joke: a tiny office, a frail director, and a mandate to do the dirtiest jobs in the name of national security. The series frequently aims its sharpest barbs at American government, media, and corporate greed, using Remo and Chiun as caustic outsiders who see through the patriotic rhetoric. Later installments lean even harder into political and cultural satire, lampooning televangelists, tech capitalism, and global politics in ways that are sometimes genuinely clever and sometimes just loud. Even when the targets feel dated or obvious, there’s a sense that Murphy is using the form of a disposable action paperback to smuggle in a surprisingly crabby worldview.

That said, this is also where the “guilty” part of the guilty pleasure label comes roaring in. By modern standards, The Destroyer is extremely non‑PC; race, gender, and nationality are all fodder for jokes that range from sharp‑edged caricature to material that many readers will reasonably find offensive. Chiun’s constant stereotyping of Americans and others is sometimes framed as a way of turning prejudice back on the majority culture, but the books often indulge in broad ethnic humor far beyond him. Women in many entries are treated primarily as scenery, sexual opportunities, or victims, though there are exceptions where they’re more capable players in the plot. If you’re reading with a contemporary lens, you’re likely to hit passages that stop you cold, and the series doesn’t apologize for any of it. Enjoyment here often requires compartmentalizing, acknowledging that the books reflect their era’s blind spots and biases while deciding whether the action and satire still outweigh that discomfort.

In terms of prose and pacing, the series is better crafted than its garish covers suggest but still rooted in the rhythms of fast‑turnaround paperbacks. The dialogue between Remo and Chiun has a crackling, insult‑laced snap that does a lot of heavy lifting in keeping you turning pages. Scenes of action are clear, efficient, and often imaginative in how Sinanju is used, even as the body count mounts to cartoonish levels. The humor, when it lands, blends deadpan absurdity with savage put‑downs, and the books occasionally deliver a line or a situational gag that feels sharper than their reputation would indicate. At the same time, the sheer volume of entries means unevenness is inevitable; some later volumes feel like they are coasting on formula, recycling set pieces and political targets with less bite. As with many long series, the high points are scattered, and part of the experience is learning which eras and authors click with you.

For readers who love action fiction, The Destroyer remains oddly addictive precisely because it refuses to be respectable. It revels in outlandish violence, outsize personalities, and unapologetic satire, while occasionally brushing up against genuine character moments in the Remo–Chiun relationship. The mythology of Sinanju, with its ancient lineage and mercenary code, gives the series a mythic backbone that most of its peers never bothered to build. At the same time, the dated politics, crude humor, and casual cruelty mean it’s not a series you recommend without caveats; it’s something you confess to loving, then immediately start explaining. If you can navigate those contradictions, The Destroyer offers exactly what its best covers promise: a relentless, often ridiculous, sometimes sharp pulp ride that you may not be proud of finishing, but will probably reach for again anyway.

Previous Guilty Pleasures

- Half-Baked

- Save The Last Dance

- Every Rose Has Its Thorns

- The Jeremy Kyle Show

- Invasion USA

- The Golden Child

- Final Destination 2

- Paparazzi

- The Principal

- The Substitute

- Terror In The Family

- Pandorum

- Lambada

- Fear

- Cocktail

- Keep Off The Grass

- Girls, Girls, Girls

- Class

- Tart

- King Kong vs. Godzilla

- Hawk the Slayer

- Battle Beyond the Stars

- Meridian

- Walk of Shame

- From Justin To Kelly

- Project Greenlight

- Sex Decoy: Love Stings

- Swimfan

- On the Line

- Wolfen

- Hail Caesar!

- It’s So Cold In The D

- In the Mix

- Healed By Grace

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Legend of Billie Jean

- Death Wish

- Shipping Wars

- Ghost Whisperer

- Parking Wars

- The Dead Are After Me

- Harper’s Island

- The Resurrection of Gavin Stone

- Paranormal State

- Utopia

- Bar Rescue

- The Powers of Matthew Star

- Spiker

- Heavenly Bodies

- Maid in Manhattan

- Rage and Honor

- Saved By The Bell 3. 21 “No Hope With Dope”

- Happy Gilmore

- Solarbabies

- The Dawn of Correction

- Once You Understand

- The Voyeurs

- Robot Jox

- Teen Wolf

- The Running Man

- Double Dragon

- Backtrack

- Julie and Jack

- Karate Warrior

- Invaders From Mars

- Cloverfield

- Aerobicide

- Blood Harvest

- Shocking Dark

- Face The Truth

- Submerged

- The Canyons

- Days of Thunder

- Van Helsing

- The Night Comes for Us

- Code of Silence

- Captain Ron

- Armageddon

- Kate’s Secret

- Point Break

- The Replacements

- The Shadow

- Meteor

- Last Action Hero

- Attack of the Killer Tomatoes

- The Horror at 37,000 Feet

- The ‘Burbs

- Lifeforce

- Highschool of the Dead

- Ice Station Zebra

- No One Lives

- Brewster’s Millions

- Porky’s

- Revenge of the Nerds

- The Delta Force

- The Hidden

- Roller Boogie

- Raw Deal

- Death Merchant Series

- Ski Patrol

- The Executioner Series