L.A. 2017 is the Steven Spielberg film about which you’ve probably never heard.

To a certain extent, that’s understandable. Spielberg was only 24 when, in 1971, he directed L.A. 2017. It was a film that he directed for television. In fact, it was only his third directorial assignment. As opposed to the huge budgets that we tend to associate with a typical Spielberg production, L.A. 2017 was made for about $300,000. The entire film was shot in about 12 days. In fact, with a running time of only a scant 69 minutes, L.A. 2017 hardly qualifies as a feature-length film. L.A. 2017 has never been released on DVD or Blu-ray, making it a true oddity in Spielberg’s filmography. Despite the fact that Spielberg has credited L.A. 2017 with opening a lot of doors for him, it’s an almost totally forgotten film.

Of course, some of that is because L.A. 2017 really isn’t a film at all. Instead, it was an episode of a television show called The Name of the Game. The show was about Glenn Howard (Gene Barry), a magazine publisher, and the reporters who worked for him. L.A. 2017 was unique in that it was the show’s only excursion into science fiction. In fact, from everything that I’ve read about the show, it appears that L.A. 2017 was nothing like any of the other episodes of The Name of the Game. This episode was also unique because Spielberg directed it as if he was making a feature, as opposed to just another installment in a weekly series. If not for the opening credits (which announce, among other things, that we’re watching a Robert Stack Production), one could easily imagine watching L.A. 2017 in a movie theater, perhaps as a double feature with Beneath The Planet Of The Apes.

L.A. 2017 opens with Glenn driving down a mountain road in California. He’s heading to a pollution summit and, as he drives along, he awkwardly dictates an editorial into a tape recorder. Glenn worries that society may have already ruined the environment to such an extent that the Earth cannot be saved. As if to prove his point, Glenn starts to cough as he’s overcome by all of the smog in the air. His car swerves into a ditch and Glenn is knocked unconscious.

Welcome to the future

When he wakes up, he finds himself being rescued by men wearing wearing protective suits and masks. The sky is a sickly orange and an ominous wind howls in the background. Glenn’s rescuers take him to an underground city where he discovers that, somehow, he has traveled through time. The year is now 2017, which in this film looks a lot like the 70s except that everyone’s now underground and the landline phones are extra bulky. (Needless to say, watching 1971’s version of 2017 in 2019 is an interesting experience.) It turns out that the pollution got so bad that the surface of the planet became uninhabitable. The U.S. is now run by a corporation that is headquartered in Detroit. (Presumably, the Corporation is a former car company.) The U.S. is also at war with England, for some reason. No mention is made about what’s happened to Canada but, if Detroit’s still around, I assume at least some of Canada managed to survive as well.

The …. uh, Future.

Everyone in the future drinks a lot of milk and, when they’re not listening to cheerful announcements, they’re listening to the soothing music that the Corporation provides for them. Everyone in the future is also very friendly. We know this because everyone keeps assuring Glenn that he’s surrounded by friends. In fact, everyone in the future refers to one another by their first name because “it’s friendlier.” It’s also the law. It turns out that there’s a lot of laws in the future. In fact, the underground cities are pretty fascist in the way that they handle things. There are constant announcements encouraging people to pursue a career in law enforcement and anyone who disagrees with the Corporation ends up in a straight jacket. Glenn feels that maybe he’s been brought to the future so he can start a new magazine and challenge the status quo. The Corporation disagrees….

This is what happens when you don’t go underground in the future.

Okay, so there’s nothing subtle about L.A. 2017. From the villainous corporation to the heavy-handed environmental message, there’s nothing here that you haven’t seen in dozens of other sci-fi films. But the lack of subtlety doesn’t matter, largely because Spielberg directs with so much energy and with such an eye to detail that it’s impossible not to get sucked into the story. As opposed to the somewhat complacent Spielberg who has recently given us rather bland and safe blockbusters like Lincoln, The BFG, and The Post, the Spielberg who directed L.A. 2017 was young and obviously eager to show off what he could do with even a low budget and that enthusiasm is present in every frame, from the wide-angle shots of Glenn driving his car to the scenes of Glenn looking up at the shadowy executives and scientists who are staring down at him when he’s first brought to the underground city. As opposed to the sterile vision of so many other future-set films, Spielberg’s future feels as if it’s actually been lived in. When Glenn finds himself in a new world, it comes across as being a real world as opposed to just a narrative contrivance.

Of course, because L.A. 2017 was just one episode in a weekly series, Glenn couldn’t remain in the future and L.A. 2017 returns Glenn to the present in the most contrived and predictable way possible. Still, L.A. 2017 remains an entertaining example of what a young and talented director can do when he’s determined to be recognized. Watching the film, it’s easy to draw a straight line from Spielberg doing L.A. 2017 to doing Duel and then subsequently being hired for Jaws.

Incidentally, Joan Crawford is somewhere in this film. Crawford worked with Spielberg when he directed her in the pilot for Night Gallery and she was one of his first major supporters in Hollywood. Apparently, in L.A. 2017, she plays one of the people staring down at Glenn when he’s first brought into the underground city. I haven’t found her yet but she’s apparently there somewhere.

Unfortunately, L.A. 2017 has never been released on DVD or Blu-ray but it is currently available on YouTube.

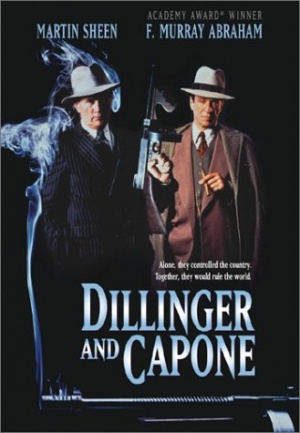

1934. Chicago. The FBI guns down a man outside of a movie theater and announces that they have finally killed John Dillinger. What the FBI doesn’t realize it that they didn’t get Dillinger. Instead they killed Dillinger’s look-alike brother. The real John Dillinger (played by Martin Sheen) has escaped. Over the next five years, under an assumed name, Dillinger goes straight, gets married, starts a farm, and lives an upstanding life. Only a few people know his secret and, unfortunately, one of them is Al Capone (F. Murray Abraham). Only recently released from prison and being driven mad by syphilis, Capone demands that Dillinger come out of retirement and pull one last job. Capone has millions of dollars stashed away in a hotel vault and he wants Dillinger to steal it for him. Just to make sure that Dillinger comes through for him, Capone is holding Dillinger’s family hostage.

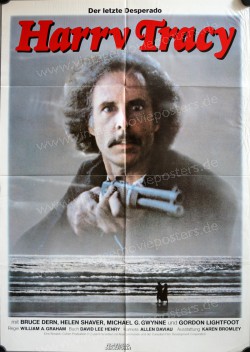

1934. Chicago. The FBI guns down a man outside of a movie theater and announces that they have finally killed John Dillinger. What the FBI doesn’t realize it that they didn’t get Dillinger. Instead they killed Dillinger’s look-alike brother. The real John Dillinger (played by Martin Sheen) has escaped. Over the next five years, under an assumed name, Dillinger goes straight, gets married, starts a farm, and lives an upstanding life. Only a few people know his secret and, unfortunately, one of them is Al Capone (F. Murray Abraham). Only recently released from prison and being driven mad by syphilis, Capone demands that Dillinger come out of retirement and pull one last job. Capone has millions of dollars stashed away in a hotel vault and he wants Dillinger to steal it for him. Just to make sure that Dillinger comes through for him, Capone is holding Dillinger’s family hostage. The year is 1902. The old west is coming to an end. Almost all of the famous outlaws are either dead or imprisoned. Only a few, like Harry Tracy (Bruce Dern), continue to make a living by robbing banks and trains. Though he is often captured and even sentenced to death a few times, Harry is always able to escape. His latest escape, from a prison in Washington, has led to the largest manhunt in American history. Harry is being pursued by a trigger-happy army, led by U.S. Marshal Morrie Nathan (played by singer Gordon Lightfoot). Harry has been in this situation before but this time, things are different. Harry is traveling with Catherine Tuttle (Helen Shaver), the daughter of a local judge. Harry and Catherine are in love but that does not matter to the men with the guns.

The year is 1902. The old west is coming to an end. Almost all of the famous outlaws are either dead or imprisoned. Only a few, like Harry Tracy (Bruce Dern), continue to make a living by robbing banks and trains. Though he is often captured and even sentenced to death a few times, Harry is always able to escape. His latest escape, from a prison in Washington, has led to the largest manhunt in American history. Harry is being pursued by a trigger-happy army, led by U.S. Marshal Morrie Nathan (played by singer Gordon Lightfoot). Harry has been in this situation before but this time, things are different. Harry is traveling with Catherine Tuttle (Helen Shaver), the daughter of a local judge. Harry and Catherine are in love but that does not matter to the men with the guns.