“Heaven and Hell are right here, behind every wall, every window, the world behind the world. And we’re smack in the middle.” — John Constantine

Constantine is one of those mid-2000s comic book adaptations that never quite hit mainstream classic status but has quietly built a loyal cult following, and it is pretty easy to see why once you revisit it. On the surface it is a supernatural action movie about a chain‑smoking exorcist stomping demons in Los Angeles; underneath, it is wrestling with guilt, faith, and whether redemption is even possible for someone who does not think they deserve it. The film is messy in spots but strangely compelling, and that tension between pulpy cool and spiritual angst is a big part of its charm.

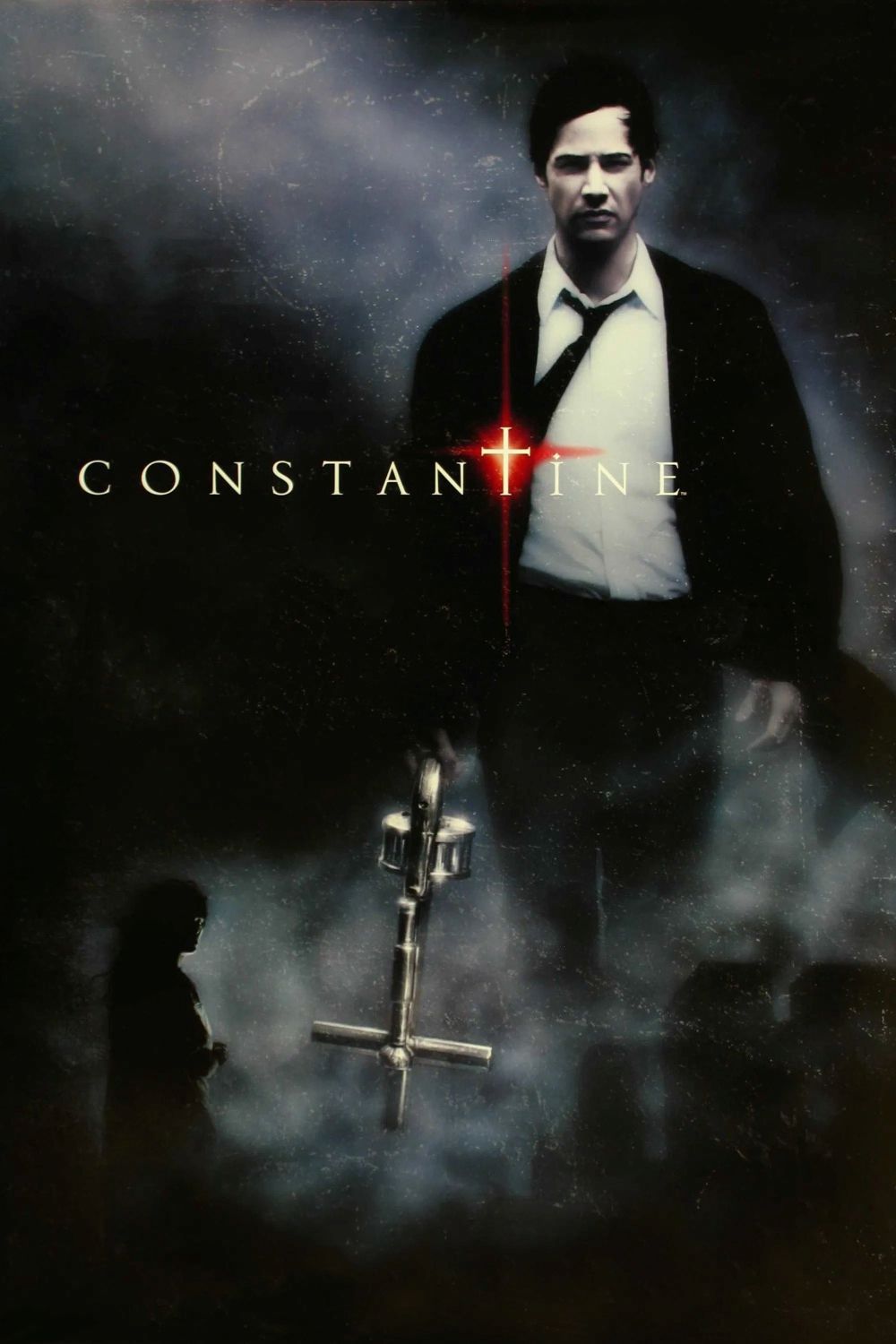

Keanu Reeves plays John Constantine as a tired, bitter man who has seen way too much of both Hell and humanity to have patience for either. This version of Constantine is loosely adapted from DC’s Hellblazer comics, but the film leans into a distinctly Hollywood noir vibe: he is not a wisecracking British punk in a tan trench coat so much as a burnt‑out L.A. exorcist in a black suit who chain‑smokes like it is a survival mechanism. That shift understandably annoyed some comic fans, but taken on its own terms, this Constantine works. Reeves’s usual reserved style actually fits a guy who has emotionally checked out; he moves through scenes like someone who has accepted that his life is transactional and almost over, and there is something darkly funny about how little awe he shows when confronted with angels and demons. Even when the script gives him on‑the‑nose lines about damnation, he plays them with a kind of deadpan resignation that keeps the character from turning into a parody.

The basic setup is simple enough: Constantine can see “half‑breeds,” angelic and demonic entities who nudge humanity toward good or evil while technically obeying a truce between Heaven and Hell. As a child, he tried to kill himself because of these visions, and that suicide attempt has doomed his soul to Hell. Now he works as a freelance exorcist, trying to earn his way back into God’s good graces, not out of pure faith but out of sheer self‑preservation. That dynamic gives the movie a strong hook—this is a protagonist who is doing the “right” thing for profoundly self‑centered reasons. When he gets pulled into a mystery involving a police detective, Angela (Rachel Weisz), investigating her twin sister’s apparent suicide, the film folds in a noirish murder case, religious prophecy, and a scheme that could break the balance between Heaven and Hell. It is all a bit overstuffed, but there is a certain pleasure in how seriously the movie commits to its supernatural mythology.

Visually, Constantine is where the film really separates itself from a lot of its contemporaries. Director Francis Lawrence leans hard into a grungy, stylized urban Hellscape—Los Angeles feels damp, sickly, and spiritually polluted even before anyone literally steps into Hell. When Constantine does cross over, Hell is portrayed as a blasted version of our world, frozen in an eternal atomic blast, buildings shattered and howling winds full of ash and debris. It is not subtle, but it is memorable, and many of the images still hold up surprisingly well for a 2005 effects‑heavy movie. The demon designs are gnarly without becoming cartoonish, the exorcism sequences have a tactile, physical quality, and the movie uses practical effects and lighting cleverly to smooth over the limitations of its CG. Even small visual touches—like holy relics turned into weapons or tattoos used as mystical triggers—help sell the idea that this world is saturated with hidden religious warfare.

The cast around Reeves does a lot of heavy lifting. Rachel Weisz brings warmth and vulnerability to Angela, grounding the story whenever it threatens to float away in theological technobabble. Her dual role as both Angela and her deceased twin gives the plot some emotional weight beyond cosmic stakes. Tilda Swinton’s Gabriel is one of the film’s secret weapons: androgynous, cool, and quietly menacing, Gabriel feels alien in a way that fits an angel who has spent too long watching humans from a distance. Then there is Peter Stormare’s Satan, who shows up late in the game and somehow steals the entire third act with a performance that is gleefully gross and oddly charismatic; his version of Lucifer is barefoot, in a white suit stained with tar, amused and disgusted by Constantine in equal measure. These performances keep the movie watchable even when the script gets tangled in its own mythology.

Tonally, Constantine lives in an odd space between horror, action, and supernatural thriller. On one hand, it has jump scares, grotesque demons, and a very dark sense of humor. On the other, it features extended action beats where Constantine straps on a holy shotgun and goes demon hunting like a paranormal hitman. The film is at its best when it leans into slow‑burn dread and eerie atmosphere—scenes like the early exorcism or Angela’s first encounters with the supernatural feel genuinely unsettling. When it shifts into more conventional action territory, it is fun but less distinctive; some sequences play like obligatory “we need a set piece here” insertions rather than organic escalations of the story. The score and sound design help stitch it all together, layering in ominous drones, choral elements, and sharp sound cues that emphasize the hellish undertones without getting too bombastic.

One of the more interesting aspects of Constantine is how it treats belief and morality. The film’s theology is a mash‑up of Catholic imagery, comic‑book lore, and Hollywood invention, and if you are looking for doctrinal accuracy, you will probably walk away frustrated. But as metaphor, it works better than it has any right to. God and the devil are treated almost like distant power brokers using Earth as their battleground, the angels and demons as middle management enforcing a “rules of the game” structure that Constantine constantly pushes against. What saves it from feeling totally cynical is that the film does not ultimately let Constantine win by gaming the system; his big climactic play hinges on a genuinely selfless act. There is a sense, however stylized, that grace and sacrifice still matter, even in a world that treats salvation like paperwork. At the same time, the movie is very much a product of its edgy 2000s era, and at points it flirts with the idea that faith is mostly about loopholes and bargaining, which might put some viewers off.

That brings up another key point: Constantine is absolutely not a family‑friendly comic book movie. It is full of disturbing imagery, body horror, and bleak subject matter like suicide, damnation, and spiritual despair. The violence is often grotesque rather than purely action‑oriented, and the general mood is closer to a horror film than a superhero romp. The R rating is well earned. For some audiences, those elements will be exactly what makes the movie interesting—a comic book adaptation that is not afraid to be nasty and heavy. For others, the relentless grimness and graphic content will feel excessive, especially when paired with a mythology that is, frankly, all over the place.

Where Constantine stumbles most is in its storytelling clarity and pacing. The film loves its jargon: half‑breeds, the Spear of Destiny, balance between realms, rules of engagement, obscure relics tossed into dialogue with minimal explanation. If you are not already inclined to meet the movie halfway, it can feel like a pile of cool‑sounding concepts that never fully cohere into a clean narrative. The central mystery—what really happened to Angela’s sister and why—is engaging early on, but as the plot widens into apocalyptic stakes, some of the emotional throughline gets lost in exposition. The pacing can be uneven too, moving from slow, moody sequences to abrupt bursts of action, then back to dense dialogue. It is rarely boring, but it can feel disjointed.

Compared to the Hellblazer source material, the film definitely sandpapers off some of John Constantine’s rougher, more politically charged edges and transplants him into a more conventional action framework. Fans of the comics often point to the loss of his British identity, the absence of his punk roots, and the more simplified view of magic and the occult as major flaws. Those criticisms are fair if you are judging the adaptation on fidelity. As a stand‑alone movie, though, Constantine carves out a distinct identity: a moody, grimy, spiritually obsessed supernatural noir built around a protagonist who is more tired than heroic. It is less about clever schemes and more about a man who has done terrible things realizing that the only way out is to finally stop acting in his own interest.

In the years since its release, Constantine has aged better than a lot of early comic book movies. The visual style remains striking, the performances are still strong, and its willingness to be weird and bleak makes it stand out in a landscape that increasingly favors quip‑heavy, crowd‑pleasing superhero fare. The flip side is that its flaws—clunky exposition, a sometimes incoherent mythology, and a very specific grim tone—are just as apparent as they were in 2005. Whether it works for you will depend a lot on how much patience you have for religious horror dressed up as action cinema. Taken as a whole, Constantine is an imperfect but memorable ride: stylish, occasionally profound, frequently ridiculous, and ultimately more interesting than many cleaner, safer adaptations.