“I don’t mind.”

— Mildred Rogers (Bette Davis) in Of Human Bondage (1934)

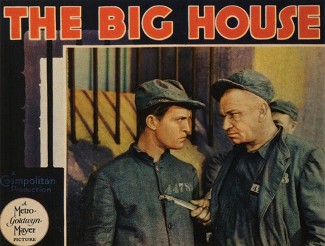

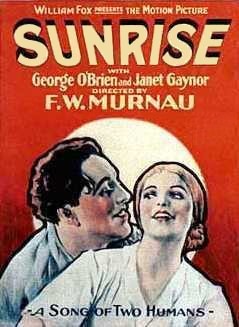

For the next three weeks, I will reviewing, in chronological order, 126 cinematic melodramas. It’s a little something that I like to call Embracing the Melodrama Part II. We started things off yesterday by taking a look at the silent classic Sunrise. Today, we continue with a quick look at the 1934 literary adaptation, Of Human Bondage.

Of Human Bondage opens with Philip Carey (Leslie Howard) living in Paris and struggling to make a living as a painter. The son of a prominent doctor, Philip is self-conscious about both his club foot and his abilities as an artist. When he invited an older artist to take a look at his work, Philip is informed, “There is no talent here. You will be nothing but mediocre.” Philip gives up his artistic ambitions and instead enters medical school.

Philip turns out to be just as miserable and moody as a medical student as he was when he was a painter. (Indeed, Philip may be one of the most miserable characters in cinematic history.) However, he does meet and becomes rather obsessed with a waitress named Mildred (Bette Davis). For her part, Mildred has little use for Philip or any of the other men who are constantly hitting on her. Whenever Philip asks her out, Mildred replies, “I don’t mind.” When Philip asks if he might kiss her goodnight, Mildred coolly replies, “No.”

Philip remains obsessed with Mildred, to the extent that he nearly flunks out of medical school because he can’t stop thinking about her. Mildred, however, eventually leaves Philip for the far more wealthy Emil Miller (Alan Hale). Eventually, Philip meets Norah (Kay Johnson), a romance novelist who falls as deeply in love with Philip as he did with Mildred. However, when the now pregnant Mildred reenters his life, Philip abandons Norah and goes back to her.

And so it goes for the next few years. Philip obsesses over Mildred. Mildred abandons Philip. Philip moves on. Mildred reenters Philip’s life. With each reappearance, Mildred appears to be growing weaker and sicker but she’s never so weak that she can’t yell at Philip and ridicule him for having a club foot…

It’s a little bit strange to admit to enjoying a film like Of Human Bondage because, when you get right down to it, it’s an unpleasant story about an unlikable man being manipulated by a heartless woman. But, interestingly enough, it’s Mildred’s unapologetic anger that make her such a compelling character. If Philip was in any way a sympathetic character, the film would be almost unbearably grim. But since Philip is such a weak-willed character and is so full of self-pity, you can’t help but be happy that Mildred is around to call him out on his bullshit. Everyone else in the film is so awful and boring, that you can’t help but appreciate the fact that Mildred never holds back.

Have you ever wondered why, every Oscar telecast, the Academy makes a point of letting us know that an independent accounting firm counted all of the ballots? Well, it’s because of this film. Or, more specifically, it’s because of Bette Davis’s ferocious performance. In 1935, when Davis somehow failed to be nominated for best actress, there was such outrage and so many people assumed that the nomination process had been rigged that the Academy actually allowed people to write in her name on their ballots. (Davis still lost to Claudette Colbert.) In order to avoid any future controversy, the Academy hired a private accounting firm to count and hold onto the ballots. (And if you’re curious about how that desire to avoid controversy is working out for the Academy, I was one words for you: Selma.) When, the next year, Bette Davis won the Oscar for best actress, it was widely assumed that it was largely to make up for being snubbed for Of Human Bondage.

If you want to see a good Leslie Howard film, go with Berkeley Square. But if you want to see a great Bette Davis film, watch Of Human Bondage.