Originally, Sergio Leone envisioned none other than Henry Fond as The Man With No Name.

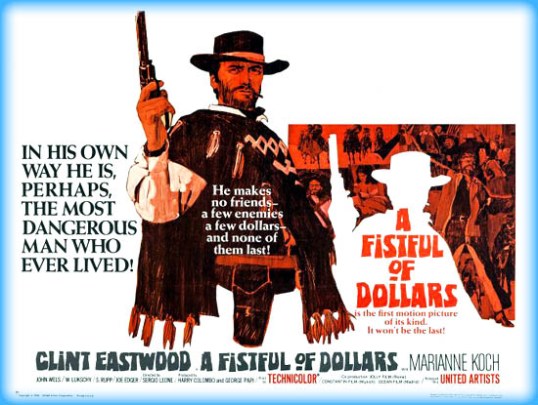

The year was 1964 and Sergio Leone was searching for the right actor to star in the movie that would become A Fistful Of Dollars. The film, which reimagined Akira Kurosawas’s Yojimbo as a western, centered around a mysterious, amoral gunslinger whose name was unknown. Leone needed an American or a British name to star in the film so that it could get distribution outside of Italy. Leone had grown up watching Henry Fonda movies, all dubbed into Italian. He later said he wanted to cast Fonda because he always wondered what Fonda’s voice actually sounded like.

After realizing that a major Hollywood star would never agree to star in a low-budget Italian western, Leone then offered the role to Charles Bronson. Bronson read the script and said it didn’t make sense to him. Leone went on to offer the role to Henry Silva, Rory Calhoun, Tony Russel, Steve Reeves, Ty Hardin, and James Coburn. Everyone was either too expensive or just not interested. Finally, it was actor Richard Harrison who, after tuning down the part himself, suggested that Leone offer the role to Clint Eastwood. Eastwood, then starring on the American western Rawhide, could play a convincing cowboy. Leone followed Harrison’s advice and Eastwood, eager to break free of his nice guy typecasting and hoping to restart his film career, accepted. The rest is history.

Eastwood would only play The Man With No Name in three films but, in doing so, he changed the movies and the popular conception of the action hero forever.

All three of the Man With No Name movies have been reviewed on this site. But, since today is Clint’s birthday, I thought I’d take a look at how these classic films are holding up, over 60 years since the Man With No Name made his first appearance.

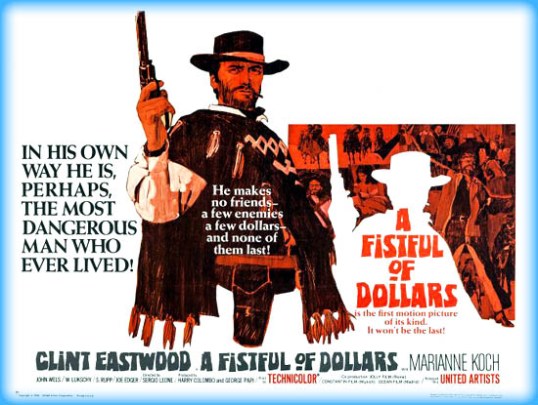

A Fistful Of Dollars (1964)

Having now seen both this film and Yojimbo, it’s remarkable how closely A Fistful of Dollars sticks to Kurosawa’s original film. Interestingly, it’s clear that Eastwood patterned his performance of Toshiro Mifune’s in Yojimbo and yet, at the same time, he still managed to make the role his own. The Man With No Name rides into a western town, discovers that there are two groups fighting for control of the area, and he coolly plays everyone against each other. Whether it’s planting the seeds of distrust, exploiting an enemy’s greed, or being the quickest on the draw, the Man With No Name instinctively knows everything that he has to do. Even when he’s getting beaten up by the bad guys, The Man With No Name always seems to be one step ahead. Today, a western in which everyone is greedy and looking out for themselves isn’t going to take anyone by surprise. But if you’ve watched enough westerns from the 40s and 50s, you’ll understand how unique of a viewpoint Leone brought to the genre. Eastwood’s amoral gunslinger was such a surprise that, when the film aired on television, a scene was shot by the network in which Harry Dean Stanton played a prison warden who released The Man With No Name (seen only from behind) on the condition that he clean up the town.

For A Few Dollars More (1965)

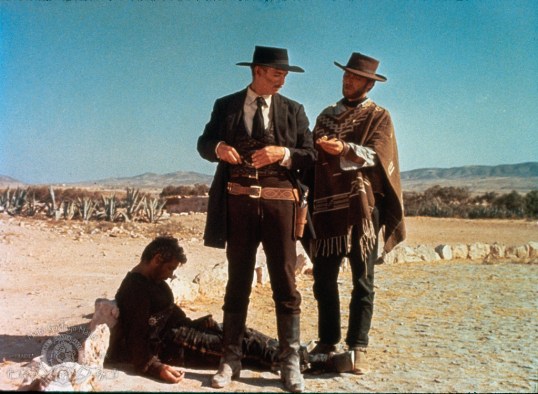

For A Few Dollars More finds The Man With No Name working as a bounty hunter and teaming up with Colonel Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef) to take down El Indio (Gian Maria Volonte) and his gang (including Klaus Kinski as a hunchback.) This is my least favorite of the trilogy but that doesn’t mean that For A Few Dollars More is a bad film. Being the least of three masterpieces is nothing to be ashamed of. Eastwood and Van Cleef were two of the best and it’s interesting to see them working together. El Indo is a truly loathsome villain and the members of his gang are all memorably horrid. If it’s my least favorite, it’s just because I prefer the wit of A Fistful of Dollars and the epic storytelling of The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. Speaking of which…

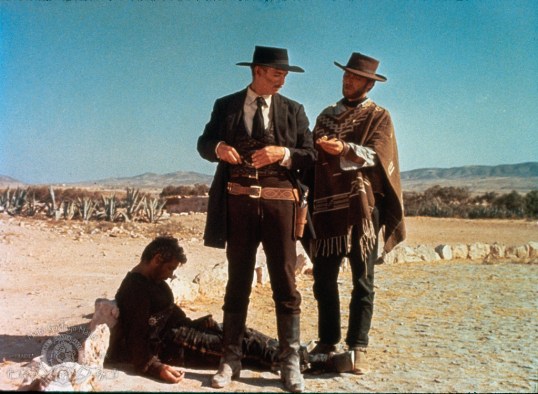

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly (1966)

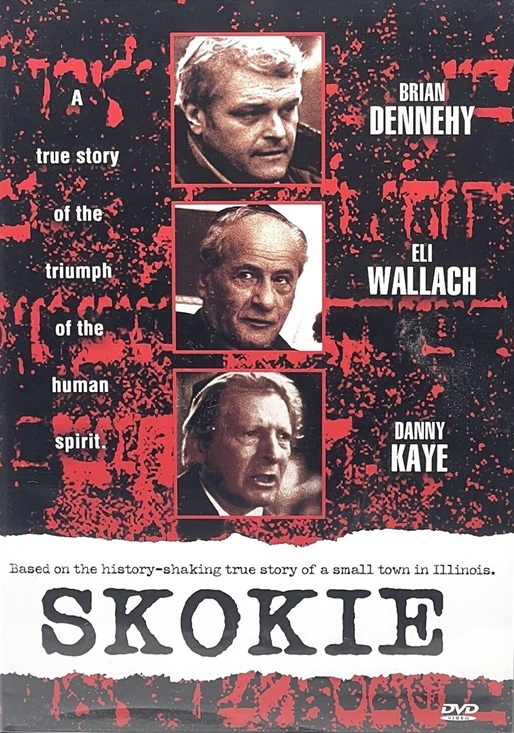

This is it. The greatest western ever made, an epic film that features Leone’s best direction, Ennio Morricone’s greatest score, and brilliant performances from Eastwood, Van Cleef, and especially Eli Wallach. It’s hard to know where to start when it comes to praising The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. It’s a nearly three-hour film that doesn’t have a single slow spot and it has some of the most iconic gunfights ever filmed. Leone truly found his aesthetic voice in this film and that it still works, after countless parodies, is evidence of how great it is. I appreciate that this film added a historical context to the adventures of The Man With No Name. (Personally, I think this film is meant to be a prequel to A Fistful of Dollars, just because The Man With No Name is considerably kinder in this film than he was in the first two movies. The Man With No Name that we meet in A Fistful of Dollars would never have gotten Tuco off that tombstone.) The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly takes place during the Civil War and, along with everything else, it’s an epic war film. While America fights to determine its future, three men search for gold. The cemetery scene will never be topped.

American critics did not initially appreciate these films but audiences did. Clint Eastwood may have been a television actor when he left for Italy but he returned as an international star. And, to think, it all started with Sergio Leone not being able to afford Henry Fonda.