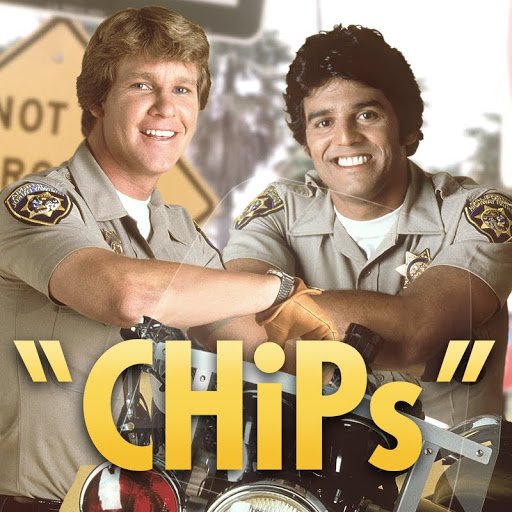

Welcome to Late Night Retro Television Reviews, a feature where we review some of our favorite and least favorite shows of the past! On Mondays, I will be reviewing CHiPs, which ran on NBC from 1977 to 1983. The entire show is currently streaming on Prime!

This week, not Ponch can smile his way out of the darkness.

Episode 4.8 “Wheels of Justice”

(Dir by Gordon Hessler, originally aired on December 21st, 1980)

The streets of Los Angeles are dangerous in this week’s episode.

Stan West (Basil Hoffman) is a reckless driver who is constantly causing accidents by driving too fast and making unsafe lane changes. He gets away with it because he keeps changing his name.

Arthur Holmes (Joshua Bryant) is a drunk who Jon and Ponch have pulled over several times. Arthur gets away with it by claiming, after every accident, that his wife was the one driving, Denise (Christine Belford) goes along with it, even though she hates the fact that she’s enabling her husband.

A group of cheerleaders drive around and do their cheers while driving!

Finally, a gas leak at the hospital leads to all the newborn babies being loaded into an ambulance for transport. When the ambulance is side-swiped by Stan, the babies end up at the station. Getraer gives everyone a lesson on how to properly soothe a crying baby. It’s cute but it’s also so manipulative that it leaves you feeling oddly used. But, hey, at least it’s cute!

This episode of CHiPs took a serious turn towards the end when the drunk driver swerved to avoid the cheerleaders and the end result is that his wife was thrown from the car and killed. When the car was shown crashing in slow motion, the wife’s mannequin actually fell out of the car. While I imagine that was probably not planned, it still created a memorably macabre image. In the end, Arthur ends up sobbing while Denise lies dead just a few feet away from him. That’s a pretty dark ending for an episode of CHiPs. Not even a quick scene of the officers holding the babies could change the fact that this was a really downbeat episode.

And you know what? There’s nothing wrong with that. Driving drunk is selfish, stupid, and dangerous and CHiPs deserves some credit for not holding back.