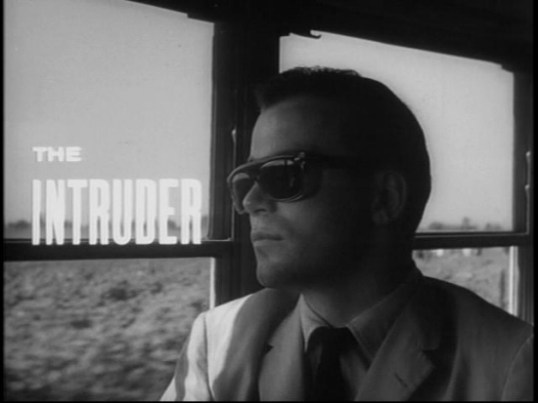

For today’s entry in the 44 Days of Paranoia, we take a look at one of the most underappreciated films of all time, Roger Corman’s 1962 look at race relations, The Intruder.

Despite the fact that he’s regularly cited as being one of the most important figures in the development of American cinema, Roger Corman remains an underrated director. Many critics tend to focus more on the filmmakers that got their start working for Corman than on Corman himself. When they talk about Roger Corman, they praise him for knowing how to exploit trends. They praise him as a marketer but, at the same time, they tend to dismiss him as a director.

I would suggest that those critics see The Intruder before they presume to say another word about Roger Corman.

The Intruder opens with a young, handsome man named Adam Cramer sitting on a bus. The first thing that we notice about Cramer is that he’s wearing an immaculate white suit. The second thing we notice is that he’s being played by a very young (and, it must be said, rather fit) William Shatner.

I know that many people will probably be inclined to dismiss The Intruder from the minute they hear that it stars William Shatner. Based simply on Shatner’s presence, they’ll assume that this film must be very campy, very Canadian, or both. Well, they’re wrong. Shatner gives an excellent performance in this film, bringing to life one of the most evil characters ever to appear on-screen.

Adam Cramer, you see, is a representative on a Northern organization known as the Patrick Henry Society and he’s riding the bus because he’s heading to a small Southern town. The high school in that town has just recently been desegregated and Cramer’s goal is to make sure that no black students attend class. As Cramer explains it, he’s a “social worker” and his goal is to help preserve Southern society.

To achieve this goal, Cramer partners up with the richest man in town, Verne Shipman (who is played, rather chillingly, by Robert Emhardt). With Verne’s sponsorship, Cramer gives an inflammatory speech in the town square and then later returns with a group of Klansmen. As opposed to recent films like Django Unchained (which scored easy laughs by casting Jonah Hill as a Klansman and playing up the group’s ignorance), The Intruder presents the Klan as figures that have stepped straight out of a nightmare, making them into literal demons who appear at night and disappear during the day. In a genuinely disturbing scene, the Klansmen set a huge cross on fire. As the flames burn behind him, Cramer seduces the wife of a local salesman.

After Cramer delivers his speech, the local black church is blown up and a clergyman is killed. The editor of the town newspaper — who, before Cramer showed up, was opposed to desegregation — changes his mind and publishes an editorial strongly condemning Cramer. Cramer’s mob reacts by nearly beating the editor to death. Realizing that he’s losing the power to control the mob that he created, Cramer frames a black student for rape which leads the film to its powerful and disturbing conclusion.

Particularly when compared to other films that attempted to deal with race relations in 1962, The Intruder remains a powerful and searing indictment of intolerance and a portrait of how demagogues like Adam Cramer will always use fear, resentment, and ignorance to build their own power. Corman filmed The Intruder on location in Missouri and used a lot of locals in the cast. Judging from the disturbing authenticity of some of the performances that Corman got from some of these nonprofessionals, it’s not unreasonable to assume that quite a few of them agreed with everything that Adam Cramer was saying.

As opposed to most films made about the civil rights era in America, The Intruder doesn’t shy away from showing the ugliness of racism. The Intruder casually tosses around the N word (and yes, it is shocking to not only hear Shatner use it but to see him smile as he does so) but, unlike a lot of contemporary films, it does so not just to shock but to show us just how naturally racism comes to the film’s characters. The scene in which Verne repeatedly strikes a black teenager who failed to call him sir is also shocking, not just for the violence but because of how nobody seems to be particularly surprised by it. As a result, The Intruder is not necessarily an easy film to watch but then again, that’s the point. The hate on display in The Intruder should never be easy to watch.

The Intruder was written by Charles Beaumont, who also wrote several classic episodes of The Twilight Zone. I think it can be argued that The Intruder represents the best work of Beaumont, Corman, and Shatner. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, The Intruder was the only film directed by Roger Corman to not be a box office success.

However, in a world where people are patting themselves on the back for sitting through The Butler, The Intruder is an important film that deserves to be seen now more than ever.