“I have seen the dark universe yawning

Where the black planets roll without aim,

Where they roll in their horror unheeded,

Without knowledge, or lustre, or name.”

― H.P. Lovecraft, Nemesis

Category Archives: Horror

Artwork of the Day: Terror Tales (by Rudolph Zirn)

Music Video of the Day: Lonely In Your Nightmare by Duran Duran (1982, directed by Russell Mulcahy)

This is one of two videos for Duran Duran’s Lonely In Your Nightmare. In this one, Simon Le Bon finds old photographs and remembers a past relationship that might have just been someone’s dream. Lonely In Your Nightmare appeared on Rio, one of the defining albums of the early 80s.

Before he made a little film called Highlander, director Russell Mulcahy was Duran Duran’s video director of choice in the early 80s and, of course, he worked with many other bands as well. His stylish music videos dominated MTV and set the template for which most subsequent videos would come.

Enjoy!

Horror On TV: The Dead Don’t Die (dir by Curtis Harrington)

For today’s horror on television, we have a 1975 made-for-television movie called The Dead Don’t Die!

The Dead Don’t Die takes place in Chicago during the 1930s. George Hamilton is a sailor who comes home just in time to witness his brother being executed for a crime that he swears he didn’t commit. Hamilton is convinced that his brother was innocent so he decides to launch an investigation of his own. This eventually leads to Hamilton not only being attacked by dead people but also discovering a plot involving a mysterious voodoo priest!

Featuring atmospheric direction for Curtis Harrington and a witty script by Robert Bloch, The Dead Don’t Die is an enjoyable horror mystery. Along with George Hamilton, the cast includes such luminaries of “old” Hollywood as Ray Milland, Ralph Meeker, Reggie Nalder, and Joan Blondell. (Admittedly, George Hamilton is not the most convincing sailor to ever appear in a movie but even his miscasting seems to work in a strange way.)

And you can watch it below!

Enjoy!

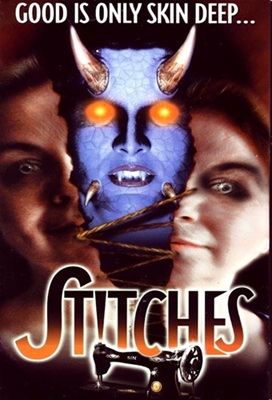

Stitches (2001, directed by Neal Marshall Stevens)

An old lady (Elizabeth Ince) stays at a boarding house at the turn of the 20th Century. At least, I think it was supposed to be the turn of the 20th Century. There weren’t any cars or telephones but, at the same time, everyone had contemporary hair styles and they wore clothes that looked like they were supposed to be vintage but actually weren’t. The movie could have just as easily been taking place in a hipster coffeehouse in 1997.

An old lady (Elizabeth Ince) stays at a boarding house at the turn of the 20th Century. At least, I think it was supposed to be the turn of the 20th Century. There weren’t any cars or telephones but, at the same time, everyone had contemporary hair styles and they wore clothes that looked like they were supposed to be vintage but actually weren’t. The movie could have just as easily been taking place in a hipster coffeehouse in 1997.

The old lady likes to walk up to people ask them if they want to see proof that demons are real and it never occurs to anyone to just say no. The woman’s back is stitched together and when those stitches are untied, she drops her skinsuit and reveals herself to be the Devil. At least, I think that’s what happened because this was one of those movies where they didn’t have the money to actually show you what happened. You just have to guess by the shadows on the wall. The film’s poster makes it look like a horrifying transformation but sometimes, posters lie.

When the old devil woman steals your soul, she turns you into a paper doll. The boarding house made decides to serve the old woman. That’s pretty much the entire story. Stretching all that out to 81 minutes took some effort and determination so I’ll give the movie credit for that.

I appreciated the movie’s ambition. It’s too bad the wooden acting and the slow pace kept this movie from being as interesting as it should have been. Today’s lesson is don’t hang out with old women who offer to show you a demon. No good will come from it.

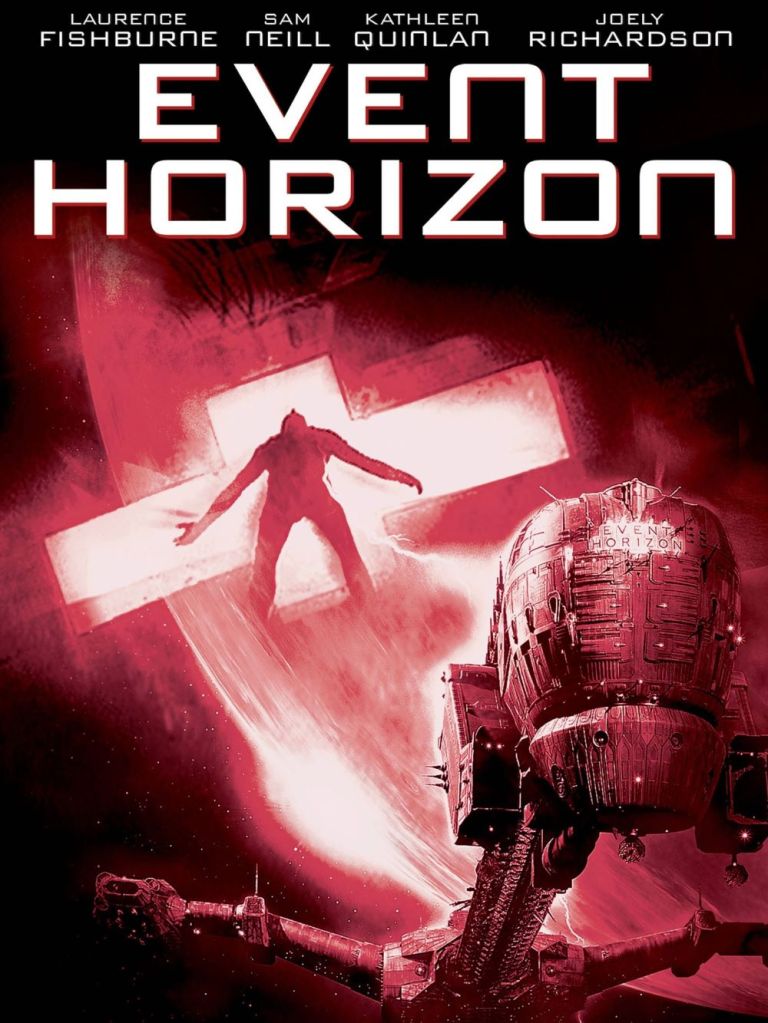

Horror Review: Event Horizon (dir. by Paul W. S. Anderson)

“You know nothing. Hell is only a word. The reality is much, much worse.” — Dr. Weir

Paul W.S. Anderson’s 1997 film Event Horizon stands out as a memorable mix of science fiction and horror, remembered for its gripping atmosphere and disturbing visuals. The story is set in 2047: a rescue crew aboard the Lewis and Clark is sent out to recover the long-missing spaceship Event Horizon, a vessel built to test a new kind of faster-than-light travel. Onboard with them is Dr. William Weir, the Event Horizon’s creator, who explains that the ship vanished after first activating its “gravity drive,” which can fold space to allow for instant travel across vast cosmic distances.

Soon after reaching the drifting Event Horizon, the crew discovers signs of mass violence and horror. They recover a disturbing audio message and realize something traumatic happened to the original crew. As they search for survivors, they experience intense and personal hallucinations—memories and fears brought to life by the ship. It becomes clear that the Event Horizon didn’t just jump through space; it traveled to a place outside reality, a nightmarish interdimensional realm resembling hell.

What makes Event Horizon particularly unique is its concept of hell as an alternate dimension that can infect and corrupt whatever or whoever crosses into it. The ship’s gravity drive doesn’t simply facilitate faster travel—it accidentally opens a gateway to this chaotic, malevolent place. This portrayal of hell as a dangerous interdimensional reality that preys on minds and bodies echoes the idea found in the massive gaming property Warhammer 40K, where hell is depicted as the Warp, a dimension of chaos that corrupts and drives people insane. Like the Warp, the film’s hell is an unpredictable, hostile realm where sanity and physical form break down, infecting and warping everything that comes into contact.

Visually, the film relies on claustrophobic corridors, flickering lights, and unsettling sounds to keep the audience off-balance. The design of the ship itself—part gothic cathedral, part industrial nightmare—adds to the sense of unease and dread throughout. The use of practical effects and detailed sets grounds the sci-fi terror in something tangible, making it all feel more immediate and believable.

Event Horizon also hints at bigger philosophical questions: how far should science go, and what happens when the drive for knowledge is unchecked by ethics or humility? The gravity drive is a technological wonder, but it’s treated with little caution by its inventor, and the catastrophic results suggest that some discoveries may be better left unexplored. The ship becomes both a literal and figurative vehicle for exploring the limits of human ambition and the dangers of pushing beyond them.

As the movie builds toward its climax, the rescue crew faces increasingly desperate odds. The possessed Dr. Weir, now an outright villain, sees the hellish dimension the gravity drive visited as the next step for humanity—a place of chaos and suffering. Multiple characters die in gruesome ways, and the survivors have to fight their own fears and the haunted ship itself. The ending is chilling and ambiguous, leaving open the possibility that the ship’s evil has not been fully contained.

At release, Event Horizon divided critics and audiences. Some found the violence and nightmare imagery too intense or the story too messy to follow. Others praised its ambition and the way it blends psychological horror with cosmic sci-fi. Over the years, the film has developed a cult reputation, frequently cited as one of the more effective and original space horror movies. Its legacy can be seen in later media, especially in video games that tackle similar haunted spaceship scenarios.

However, the film is not without flaws. Many viewers and critics point out uneven pacing, especially in the second half where tension sometimes drains away. The characters often act inconsistently or make choices that feel unrealistic for trained astronauts, which undermines the suspense. The script’s tonal shifts—from serious psychological drama to moments that unintentionally verge on camp—can jolt the viewer out of the experience. The use of jump scares is sometimes predictable, and the film’s heavy reliance on loud, chaotic sequences instead of quiet suspense can feel overwhelming. Some CGI effects haven’t aged well, contrasting with the otherwise impressive practical effects and set design. Acting performances are mixed too; while Sam Neill and Laurence Fishburne are strong, some supporting cast members lack conviction, making emotional engagement uneven.

Importantly, Event Horizon represents Paul W.S. Anderson at his most subtle and effective in directing. Compared to many of his later films, where his style often becomes frenetic and unchecked—possibly due to a lack of producer control—Event Horizon is more controlled, atmospheric, and haunting. This balance between style and substance makes it one of Anderson’s better directorial works, if not his best to date. The film showcases his interest in spatial geography, the use of negative space, and claustrophobic production design, all elements he would expand on in his later work but never as effectively deployed as here. The haunting visual touches, combined with his ability to direct actors and maintain tension, set Event Horizon apart from his more bombastic, less focused later entries.

Despite its flaws, Event Horizon remains gripping and memorable. Its strengths lie in combining deeply personal psychological horror with the vast, terrifying unknown of space and alternate realities. The film explores not just external threats, but also how guilt, fear, and trauma can be weaponized by forces beyond human understanding. For viewers seeking more than a standard haunted spaceship story, Event Horizon offers a disturbing, thought-provoking glimpse into the dark frontier of science, faith, and madness. It stands as a cult classic of sci-fi horror that continues to inspire discussion about the dangers of pushing too far into the unknown.

Horror Scenes That I Love: The Man Behind The Dumpster From Mulholland Drive

October True Crime: Too Close To Home (dir by Bill Corcoran)

The 1997 film Too Close To Comfort tells the disturbing story of the Donahues.

Nick Donahue (Rick Schroder) is a young attorney, a law school grad who has just joined the bar and who is still making a name for himself as a defense attorney. He’s good at his job and if you have any doubts, his mother Diane (Judith Light) will be there to tell you why you’re incorrect. Diane and Nick still live together. They have the type of relationship where Diane casually walks into the bathroom to talk to Nick while he’s in the shower.

In short, they have a very creepy relationship.

Nick talks about needing to get a place of his own but his mother says that it’s too soon for him to spend all that money. Nick wants to fall in love and marry a nice girl and start a family. Diane doesn’t want Nick to have a life separate from her. When Nick does end up marrying the sweet-natured Abby (Sarah Trigger), Diane snaps. One night, Abby is abducted and is later found murdered. Nick sobs and Diane holds her son and she doesn’t mention the fact that she’s the one who arranged for Abby to be killed.

The police figure it out, of course. Diane wasn’t that clever. When Diane is arrested and put on trial for murder, Nick is shocked. With his mother facing the death penalty for murdering his wife, Nick steps forward to defend his mother in court.

Agck! This movie! Admittedly, this is a made-for-TV movie but it’s still creepy as Hell. If anything, the fact that it was made for television make it even creepier than if it was a uncensored feature film. Held back by the rule of television, the film has to hint at what would probably otherwise be portrayed as explicit. That makes all of the little moments that indicate Diane’s madness all the more disturbing and frightening because they could be read several different ways. This is a film where every line is full of a very icky subtext. Diane is more than just an overprotective mother. Her feelings for Nick are on a whole other level.

Fortunately, Judith Light is one of those actresses who excels at communicating subtext. She delivers every line with just enough of an inflection that we know what she’s saying even if she doesn’t actually say it. From rolling her eyes when Nick asks her to turn around when he gets out of the shower to the scene where she flirts with Nick’s new landlord, Light leaves little doubt as to what really going through Diane’s mind. Rick Schroder has a far more simpler role as Nick but he still does a good job with the role. He’s sympathetic, even when he’s refusing to accept the truth about his mother.

This film is all the more disturbing due to being loosely based on a true story. The real Diana Donahue was named Elizabeth Ann Duncan and she was convicted of killing her son’s wife in the 1950s. (Too Close To Home is set in the 90s.) Her son really did defend her, all the way until her execution. In real life, her son continued to practice law until 2023, when he was disbarred by the state of California.

As for the film, it’s a classic true crime made-for-TV movie that features Judith Light at her disturbing best.

Horror Song Of The Day: The Lions and the Cucumber by The Vampires’ Sound Incorporation

Today’s song of the day comes from the 1971 film, Vampyros Lesbos. The Vampires’ Sound Incorporation was a band specifically formed to do the soundtrack for Jess Franco’s classic portrait of Eurotrash decadence. This song found renewed popularity in the 90s when Quentin Tarantino included it on the Jackie Brown soundtrack.

I like this song. It’s great driving music and it sounds like something that a vampire would actually listen to.

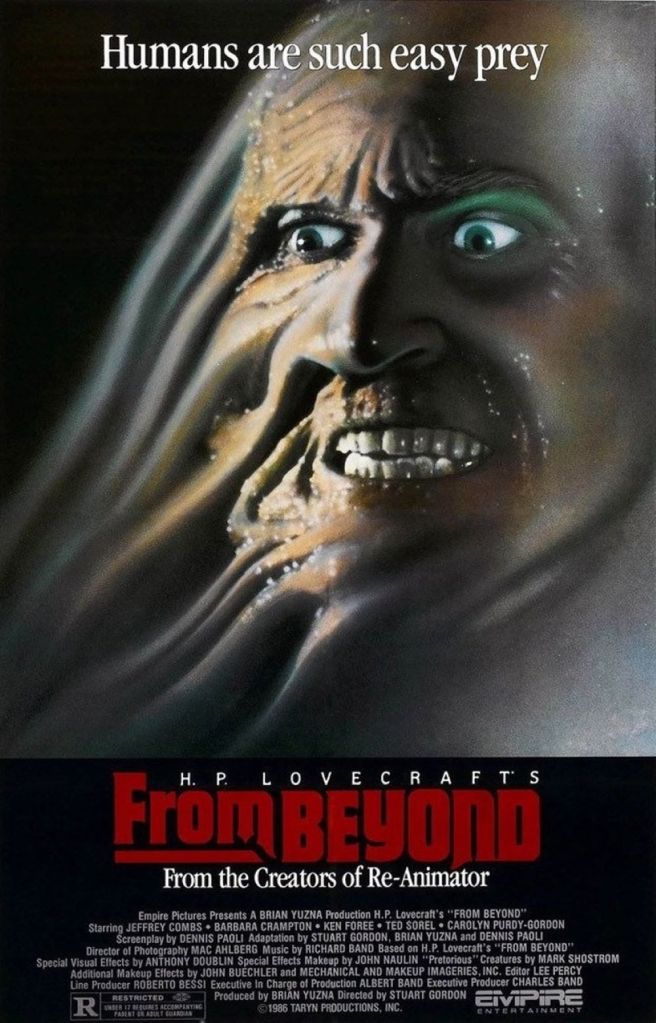

Horror Review: From Beyond (dir. by Stuart Gordon)

“You’re diving deeper than any sane man ever should.” — Dr. Katherine McMichaels

Stuart Gordon’s From Beyond (1986) stands as a darker, moodier follow-up to his breakout Lovecraft adaptation, Re-Animator (1985). At its core is the Resonator, a bizarre scientific contraption designed to stimulate the pineal gland—allowing its users to glimpse eerie creatures and dimensions normally invisible to the naked eye. When Dr. Crawford Tillinghast (Jeffrey Combs) activates the device, it unleashes horrors not just upon the world but also within the minds and bodies of those involved, blurring the line between reality and nightmare in a way both terrifying and hypnotic.

Just like with Re-Animator, Gordon used H.P. Lovecraft’s short story From Beyond as a foundation but expanded the narrative significantly by injecting his own creative vision and filling in what Lovecraft left unexplored. Lovecraft’s original story is a brief, eerie vignette about stimulating the pineal gland to perceive alternate dimensions and terrifying alien creatures—minimalistic and atmospheric, leaving much to the imagination. Gordon reimagines this premise into a fully fleshed-out narrative, adding complex characters like the obsessive Dr. Edward Pretorius and the rational yet vulnerable Dr. Katherine McMichaels. He enriches the story with body horror, psychological torment, and a deeper thematic exploration of sexuality, obsession, and the fragility of the mind. This creative expansion transforms the story into something far more personal and tangible, blending cosmic horror with primal human fears and desires.

This tonal shift stands in stark contrast to Re-Animator, which thrives on anarchic gore, slapstick comedy, and a playful mad-scientist energy. From Beyond trades much of the humor for a somber, unsettling atmosphere drenched in slime, grotesque transformations, and claustrophobic dread. The characters are more grounded in psychological trauma, and the film’s pacing emphasizes creeping unease rather than chaotic spectacle. Gordon’s use of stark, hallucinatory lighting and saturated colors enhances this otherworldly feeling, while practical effects bring a tactile horror to life that heightens the visceral and emotional impact. The horror isn’t just external—it’s internal, a fracture of reality and self.

One of the most notable ways From Beyond separates itself from Gordon’s earlier work is in its overt intertwining of sexuality and horror. The Resonator doesn’t just expose alien creatures; it unlocks primal lust and repressed desires in its users. Scenes imbued with uneasy erotic tension, especially involving Barbara Crampton’s character, make sexuality a core source of vulnerability and terror. This blend of eroticism and nightmare adds depth and psychological complexity, exploring how intimate human experiences can be distorted into something terrifying. It’s a thematic boldness that would become highly influential beyond Western cinema.

Indeed, the film’s fusion of sexual subtext, body horror, and psychological unease foreshadowed themes embraced by late 1980s and early 1990s Japanese horror hentai anime. Works such as Angel of Darkness (Injū Kyōshi) combined explicit eroticism, grotesque body transformations, and supernatural horror in ways reminiscent of From Beyond’s style and tone. This synergy helped define a subgenre of adult horror anime where the boundaries between pleasure and terror, desire and monstrosity, are constantly blurred—cementing From Beyond not only as a cult classic in horror but also as an inspirational bridge to pioneering adult animation in Japan.

Visually and atmospherically, the film is a masterpiece of practical effects and immersive storytelling. The slime-drenched creatures, anatomically warped bodies, and constant visual flow between nightmare and distorted reality create a hallucinatory experience. The climax offers a frenetic, visceral battle that embodies the film’s core themes of madness, transformation, and cosmic terror, leaving viewers with a lingering sense of unease and wonder.

Stuart Gordon’s direction also employs incredibly effective subjective perspectives, with many scenes shot from the characters’ points of view. This technique immerses viewers in the unfolding madness and heightens the sensory overload that defines the film’s experience. There is a famously unsettling point-of-view shot from the mutated Crawford as he perceives a brain inside a doctor’s head and gruesomely attacks. Such moments amplify the film’s exploration of altered perception and the treacherous expansion of human senses.

Despite these strengths, the film is not without flaws. Ken Foree’s character, Bubba Brownlee, while providing moments of grounded streetwise humor, sometimes comes off as a caricature that leans into stereotypical portrayals of Black men as taboo or outlier figures in horror cinema. This portrayal feels somewhat jarring against the film’s otherwise nuanced tone and may evoke discomfort.

Additionally, From Beyond can feel comparatively stiff and sluggish next to Re-Animator, lacking some of the earlier film’s darkly comic energy. The story often relies on a series of increasingly grotesque set pieces that feel more like shock showcases than a cohesive narrative arc. Some performances, including Jeffrey Combs’ lead, occasionally seem overly intense without sufficient emotional variation, and the film sometimes slips into melodrama that undercuts its impact. Furthermore, although ambitious in visualizing Lovecraftian horrors, budgetary constraints are occasionally evident, diminishing some of the awe those moments seek to inspire.

Ultimately, Gordon’s From Beyond is a significant Lovecraft adaptation that showcases the power of expanding upon source material with bold creativity. Moving beyond Lovecraft’s sparse prose, Gordon infuses the story with rich characters, psychological depth, explicit body horror, and mature explorations of sexuality. This results in a haunting, distinctly unsettling film that not only stands as a high point in Gordon’s career but also resonates far beyond its American horror roots, shaping international horror aesthetics and inspiring future genres. It is a disturbing, thrilling journey to the dark spaces just beyond human perception—a cinematic experience that lingers in the mind long after the screen fades to black.