2024’s The Old Ones opens with an animated sequence of an old sea captain being tossed into a light, an apparent sacrifice. On the one hand, it’s properly macabre, featuring as it does a cult sacrifice. On the other hand, it’s also kind of cute because it’s animated. That juxtaposition between the horrific and the cute pretty much defines the entire film.

The sea captain is Russell Marsh (Robert Miano). He eventually washes up, 95 years after he left his home on a sea voyage. Russell is discovered by Dan (Scott Vogel) and his son, Gideon (Brandon Philip), who are camping and having some father-and-son bonding time. Russell tells them that he was born in 1865 and that he last set sail in 1930. Dan and Gideon point that’s not possible because it’s 2025 and Russell doesn’t appear to be a day over 65. Russell says that he’s spent the last 95 year being possessed and controlled by the Old Ones, the cosmic beings who control the universe. Dan is skeptical but then Dan is promptly killed by a monster who materializes out of nowhere. Russell and Gideon go on the run, trying to avoid cultists and others who have been possessed by the Old Ones. Russell says that, if he can find the mysterious Nylarlahotep, he may be able to travel through time and stop himself from going to sea in 1930. Russell would never be possessed by the Old Ones and, in theory, Gideon’s father would never had died.

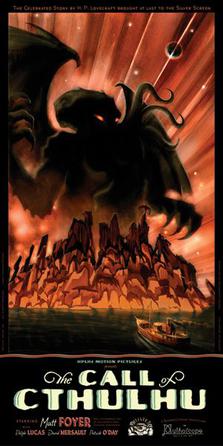

The Old Ones is “based on the writings of H.P. Lovecraft” and it should be noted that the film does contain references to a lot of Lovecraft’s stories. Nylarlahotep (played here by Rico E. Anderson) is a character straight out of Lovecraft and his behavior here — menacing and enigmatic, if slightly bemused by the foolishness of humanity — very much conforms to Lovecraft’s portrayal of him. The Old Ones will be familiar to anyone with even a passing knowledge of the Cthulhu Mythos. That said, the film itself doesn’t always feel particularly Lovecraftian, if just because of the amount of humor that is found during Russell and Gideon’s quest. Gideon is often in a state of shock while Russell is the one who has seen it all and faces every horror with a studied nonchalance.

(One of the film’s best moments is when Russell pragmatically suggests that Gideon should sacrifice himself since Russell is just going to reverse time anyways.)

Considering that the budget was obviously low and that the writings of H.P. Lovecraft are notoriously difficult to adapt, The Old Ones works far better than I certainly expected it to. The story moves quickly and even the humor adds to the overall feel of the chaotic energy of the Old Ones invading human existence. The strongest thing about the film is the performance as Robert Miano as Russell Marsh. As played by Miano, Russell is the perfect hero for this type of story, compassionate but also pragmatic enough not to shed any tears if someone happens to die on Russell’s way to reversing time. Even if the humor may not reflect the source material, the film still ends on a very Lovecraftian note. One person’s happy ending is another’s nightmare.