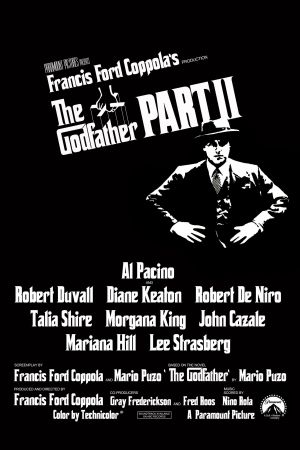

Years ago, I wrote a post called What Could Have Been: The Godfather, in which I discussed all of the actors and the directors who were considered for The Godfather.

It remains one of the most widely viewed posts that we’ve ever had on this site. I guess that shouldn’t be a surprise. People love The Godfather and they love playing What If? Would The Godfather still have been a classic if it had been directed by Otto Preminger with George C. Scott, Michael Parks, Burt Reynolds, and Robert Vaughn in the lead roles? Hmmm …. probably not. But, in theory, it could have happened. All of them were considered at one point or another.

However, in the end, it was Francis Ford Coppola who directed The Godfather and it was Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Cann, and Robert Duvall who brought the Corleone family to life. The Godfather, as everyone knows, was a huge hit and it went on to win the Oscar for Best Picture of the year. As the film ended with the future of the Corleone family still up in the air, there was obviously room for a sequel.

When Paramount Pictures first approached Coppola about writing and directing a sequel, he turned them down. He said he was done with The Godfather and didn’t see any way that he could improve on the story. It’s debatable whether or not Coppola truly felt like this or if he was just holding out for more money. It is known that Coppola did suggest to Paramount a possible director for Part II and that director’s name was Martin Scorsese.

What would Martin Scorsese’s The Godfather Part II have looked like? It’s an intriguing thought. At the time, Scorsese was best-known for Mean Streets and it’s probable that Scorsese’s film would have been a bit messier and grittier than Coppola’s version. If Coppola made films about the upper echelons of the Mafia, Scorsese’s interest would probably have been with the soldiers carrying out Michael’s orders. While Scorsese has certainly proven that he can handle a huge productions today, he was considerably younger and much more inexperienced in the early 70s. To be honest, it’s easy to imagine Scorsese’s Godfather Part II being critically and commercially rejected because it would have been so different from Coppola’s. A failure of that magnitude would have set back Scorsese’s career and perhaps even led to him returning to Roger Corman’s production company. As such, it’s for probably for the best that Coppola did eventually agree to shoot the sequel, on the condition that Coppola be given creative control and Paramount exec Robert Evans not be allowed on the set. While Coppola was busy with Godfather Part II, Scorsese was proving his versatility with Alice Doesn’t Live Her Anymore.

After Coppola was signed to direct, the next best question was whether or not Marlon Brando would return to play the role of Vito Corleone. The film’s flashback structure would ensure that Vito would remain an important character, despite his death in the first film. Coppola reportedly considered offering Brando the chance to play the younger version of Vito but he changed his mind after he saw Robert De Niro in Scorsese’s Mean Streets. Still, it was felt that Brando might be willing to show up in a cameo during the film’s final flashback, in which Michael tells his family that he’s enlisted in the army. Frustrated by Brando’s refusal to commit to doing the cameo, Coppola told him to show up on the day of shooting if he wanted to do the film. When Brando didn’t show, the Don’s lines were instead rewritten and given to Tom Hagen. It’s hard not to feel that this worked to the film’s advantage. A last-minute appearance by Brando would have thrown off the film’s delicate balance and probably would have devalued De Niro’s own performance as the younger version of the character.

Brando wasn’t the only member of the original cast who was hesitant about returning. Al Pacino held out for more money, which makes sense since he was literally the only cast member who could not, in some way, be replaced. Richard Castellano, who played Clemenza in the first film, however learned that he that hard way that he was not quite as indispensable as Al Pacino. In Part II, Clemenza was originally meant to have a large role in both the flashbacks and the present-day scenes. However, when Castellano demanded more money and the right to rewrite his own lines, the older Clemenza was written out the film and replaced by the character of Frankie Petangeli (played by Michael V. Gazzo).

It’s impossible to find fault with Gazzo’s performance but it’s still hard not to regret that Castellano didn’t return. Imagine how even more poignant the film’s final moments would have been if it had been the previously loyal Clemenza who nearly betrayed Michael as opposed to Frankie? Indeed, even after the part was rewritten, many of Frankie’s lines deliberately harken back to things that Clemenza said and did during the first film. Because Clemenza is a very prominent character during the film’s flashbacks, his absence in the “modern” scenes is all the more obvious.

When the role of Young Clemenza was cast, it was still believed that Richard Castellano would be appearing in that film. One of the main reasons that Bruno Kirby was selected for the role of Young Clemenza was because Kirby had previously played Castellano’s son in a television show. Also considered for the role was Joe Pesci, who was working as a singer and a comedian at the time. (His partner in his comedy act was Frank Vincnet.) If Pesci had been cast, he would not only have made his film debut in The Godfather Part II but the film also would have been his first pairing with Robert De Niro. (Interestingly enough, Frank Sivero — who played Pesci and De Niro’s henchman, Frankie Carbone, in Goodfellas, also had a small role in Godfather Part II, playing Vito’s friend, Genco.)

As for the film’s other new major character, there were several interesting names mentioned for the role of gangster Hyman Roth. Director Sam Fuller read for the role and Coppola also considered Elia Kazan. Perhaps the most intriguing name mentioned as a possible Roth was that of James Cagney. (Cagney, however, made it clear that he was content to remain retired.) In the end, the role was offered to Al Pacino’s former acting teacher, Lee Strasberg. Like Gazzo, Strasberg made his film debut in The Godfather Part II and, like Gazzo, he received his only Oscar nomination as a result.

The legendary character actor Timothy Carey (who was courted to play Luca Brasi in the first film) met with Coppola to discuss playing Don Fanucci, the gangster who is assassinated by Vito. A favorite of Stanley Kubrick’s, Carey reportedly lost the role when he pulled out a gun in the middle of the meeting.

Originally, the film was supposed to end in the mid-60s, with a now teenage Anthony Corleone telling Michael that he wanted nothing to do with him because he knew that Michael had Fredo murdered. (That famous scene of Michael bowing his head was originally supposed to be in response to Anthony walking out on him as opposed to the sound of Fredo being shot.) Cast in the role of teenage Anthony was actor Robby Benson so perhaps it’s for the best that the scene was ultimately not included in the film.

Some of the smaller roles in Part II were played by actors who were considered for larger roles in the first film. The young Tessio was played by John Aprea, who was also considered for the role of Michael. Peter Donat, who played the lead Senate counsel in Part II, was considered for the role of Tom Hagen. The rather tall Carmine Caridi, who played Camine Rosato in Part II, was originally cast as Sonny until it was discovered that he towered over everyone else in the cast. And, of course, Robert De Niro famously read for the role of Sonny and was cast in the small role of Paule Gatto before he left The Godfather to replace Al Pacino in The Gang Who Couldn’t Shoot Straight. (Of course, the whole reason that Pacino left The Gang Who Couldn’t Shoot Straight was so he could play the role of Michael in The Godfather. In the end, it all worked out for the best.)

Finally, former teen idol Troy Donahue played Connie Corleone’s second husband, Merle Johnson. Merle Johnson was Troy Donahue’s real name.

Personally, I think The Godfather Part II is one of the few films that can be described as perfect. Still, it’s always fun to play what if.