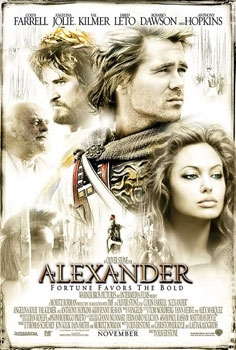

Before I really get into talking about Oliver Stone’s 2004 film, Alexander, I should acknowledge that there’s about four different version of Alexander floating around.

There’s the widely ridiculed theatrical version, which was released in 2004 and which got terrible reviews in the United States, though it was apparently a bit more popular in Europe. This version of Alexander was a notorious box office bomb and Oliver Stone’s career has never quite recovered from it. Though Stone’s still making movies, it’s been a while since he’s really been taken as seriously as you might expect a two-time Oscar winner to be taken. The box office and critical failure of Alexander is a big reason for that.

There’s also the Director’s Cut of Alexander, which is slightly shorter than the version that was released into theaters and which apparently emphasizes the action scenes more than the original film did. For an Oscar-winning director to release a director’s cut that’s actually shorter than the version that he originally sent into theaters is rare and it shows that the film’s subject matter was one that Stone was still trying to figure out how to deal with.

There is also the “Final Unrated Cut,” which lasts 3 hours and 45 minutes and which Stone described as being the Cecil B. DeMille-version of the story. At the time the Final Unrated Cut was released in 2007, Stone announced that he had put everything back into the movie and that we were finally able to see the version of the story that he wanted to tell.

However, Stone apparently still left some stuff out because, in 2009, we got the Final Cut, which goes on for 206 minutes and which, once again, apparently includes everything that Stone wanted to put in the original cut of the film. The Final Cut has actually received some positive reviews from critic who were not impressed by the previous three versions of Alexander.

For the record, I saw the Director’s Cut. This is the second of the Alexanders, the one that runs 167 minutes. Some day, I’ll watch the four hour version and I’ll compare the two films. But for now, I’m reviewing the 167-minute version of Alexander.

Anyway, Alexander is a biopic of Alexander The Great, the Macedonian ruler who took over a good deal of the known world before mysteriously dying at the age of 32. The film jumps back and forth in time, from an elderly Ptolemy (Anthony Hopkins, going about as overboard as one can go while playing an ancient Greek historian) narrating the story of Alexander’s life to Alexander (Colin Farrell) conquering his enemies to scenes of Alexander’s mother (Angelina Jolie) and one-eyed father (Val Kilmer) shaping Alexander’s outlook on the world. Along the way, we discover that Alexander was driven to succeed and forever lived in the shadow of his father. We also discover that he may have been in love with his general, Hephaistion (Jared Leto), even though he married Roxane (Rosario Dawson, who gets to do an elaborate dance). We also discover that no battle in the ancient world could begin before Alexander gave a long speech and that all of the Macedonians spoke with thick Irish accents. Stone has said that the Irish accents were meant to signify that the Macedonians were working-class. Other people say that, because Colin Farrell’s accent was so thick, the rest of the cast had to imitate him so he wouldn’t sound out-of-place.

And here’s the thing — yes, Alexander is a big, messy film that is often incoherent. Yes, the cast is full of talented actors, every single one of which has been thoroughly miscast. Yes, it’s next to impossible to keep track of who is fighting who and yes, it’s distracting as Hell that all of the Macedonians have Irish accents and that Angelina Jolie uses an Eastern European accent that’s so thick that it almost becomes a parody of itself. All of these things are true and yet, I was never bored with the director’s cut. The sets were huge, the costumes were beautiful, and the cast was eccentric enough to be interesting. Val Kilmer, Angelina Jolie, and Anthony Hopkins all go overboard, chewing every piece of scenery that they can get their hands on. Colin Farrell alternates between being determined and being wild-eyed. Jared Leto allows his piercing stare to do most of his acting. Even Christopher Plummer shows up, playing Aristole with a North Atlantic accent. No one appears to be acting in the same film and strangely, it works. The ancient world was chaotic and the combination of everyone’s different acting styles with Stone’s frantic direction actually manages to capture some of that chaos.

Oliver Stone apparently spent years trying to bring his vision of Alexander’s life to the big screen. Watching the film, it’s a classic example of a director becoming so obsessed with a story that they ultimately forgot why they wanted to tell it in the first place. Stone tosses everything he can at the cinematic wall, just to see what will stick. Is Alexander a tyrant or a misunderstood humanist? Is he a murderer or a noble warrior? Is he in love with Hephaistion or has his borderline incestuous relationship with his mother left him incapable of trusting anyone enough to love them? The film doesn’t seem to know who Alexander actually was but it’s so desperate to try to find an answer among all of the endless battle scenes and lengthy speeches that it becomes undeniably compelling to watch. If nothing else, Alexander gives us the rare chance to see an Oliver Stone film in which Stone himself doesn’t seem to quite know what point it is that he’s trying to make.

Alexander is a mess but there’s something fascinating about its chaos. It’s a beautiful wreck and, as with all wrecks, it’s impossible to look away.