Once upon a time, in 19th century Germany, there was a young man who was known as Kaspar Hauser.

No one was really sure what Kaspar’s original name was or where he even came from. He was found, in 1828, wandering the streets of Nuremberg. He carried an unsigned letter with him, one that said that he was 16 yeas old, from the Bavarian border, and that he had been raised by someone who taught him how to read and write and about “the Christian religion.” The note also stated that the boy had never been allowed to step out of the house before being taken and abandoned in Nuremberg. He carried a second letter, which was supposedly from his mother and stated that the boy’s name was Kaspar and that his father had been in the Cavalry. Some people who saw the two letters felt that they had both been written in the same handwriting, leading to speculation that Kaspar may written the letters himself.

When he was first found, it was believed that Kaspar could barely speak. He knew the word for “Horses!” and he often repeated the phrase, “My father was cavalryman!” As time progressed, Kaspar’s vocabulary expanded and he said that his earliest memories were of being locked away in a room. His meals were brought to him by someone who always wore a mask. Some people felt that Kaspar may have been the kidnapped child of a nobleman or an unacknowledged member of the royal family. Others felt that he was a charlatan and that he was faking the entire thing. Briefly, Kaspar was a celebrity as people from around the world wondered who he was and where he had come from.

In 1828, he was found with a cut on his forehead. He said that he was attacked by a mysterious stranger who announced, before cutting him, “You have to die!” The stranger was never found and there was even some speculation that Hauser had cut himself. In 1830, he was found with another wound on his forehead, this time claiming that he had been grazed by a bullet after a gun accidentally went off. Again, some felt that Hauser was intentionally injuring himself for the attention while others felt that the people who had held him prisoner were again trying to kill him.

Hauser was found wounded one last time, in 1833. This time, he was found with a deep cut to his chest. He claimed that he had, again, been attacked by a mysterious stranger. A note was found where Hauser claimed that he had been attacked, a cryptic letter that claimed that the attacker was the same man who had previously cut Hauser’s head. By this point, there was a lot more skepticism about Hauser and his stories and it was generally assumed that he had stabbed himself and injured himself worse than he ha intended. It’s said that when Hauser died of his wounds, his last words were, “I didn’t do it to myself.” Assuming that Hauser was born when the note from his mother claimed that he was, Kaspar Hauser was 21 when he died.

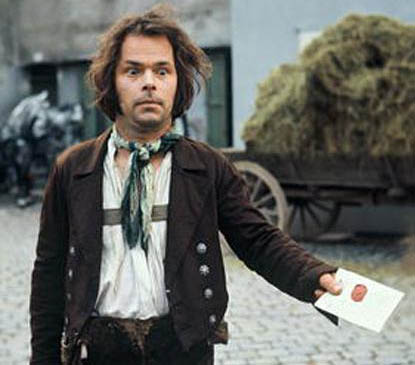

The mystery of Kaspar Hauser is an intriguing one and it’s one that’s explored in Werner Herzog’s 1974 film, The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser. The film sticks fairly closely to the known facts of Hauser’s life. For instance, Herzog does not show us the final attack on Hauser. Instead, he just has Hauser tell us about the attack, leaving it to us to decide whether or not Kaspar is telling the truth. At the same time, the film starts with footage of Kaspar being held in a small room. We watch as a dark-clad stranger carries Hauser to Nuremberg and, after showing him how to walk, then abandons him on the streets of the city. Herzog accepts Hauser’s claim that he was raised in a locked room but he leaves it to us to decide why Hauser was in that room and why he was eventually abandoned in Nuremberg.

Kaspar Hauser is played by an actor named Bruno S. Bruno S. was a nonprofessional and he was 42 year-old when he played the 16 year-old Hauser. And yet, Bruno S. has such an unconventional screen presence that he seems perfect for the role. With his wide-eyed stare and his tentative movements, Bruno S. is poignantly believable as someone who is discovering the world for the same time. As the film progresses, Hauser develops a sharp and cynical wit, all of which Bruno S. captures perfectly.

Hauser is another Herzog protagonist who, because he’s on the outside of regular society, has developed the ability to see the world in a way that no one else can. While he lays dying, Hauser has visions of nomadic Berbers in the Sahara Desert. Why? Why not? That’s the enigma of Kaspar Hauser. As in all of his best films, Herzog embraces the questions without trying to manufacture answers and the end result is a haunting film about one of Germany’s most enduring historical mysteries.