After watching Getting Straight, I decided to watch another student protest film from 1970, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point. Much like Otto Preminger’s Hurry Sundown, Zabriskie Point is a film that frequently gets mentioned when film bloggers are trying to list the worst films of all time. Unlike Hurry Sundown, Zabriskie Point is not quite as terrible as some reviewers seem to think.

It’s probably a mistake to describe Zabriskie Point as being as a college film. Only one of the main characters — Mark (played by Mark Frechette) — is a college student and he drops out early in the film. The film’s other main character — Daria (played by Daria Halperin) — is a secretary who may (or may not) be the mistress of venal real estate developer Lee Allen (played by Rod Taylor, the sole professional actor out of the starring cast). However, the film does start on a college campus, it deals with political protest (which was apparently the only thing happening on campuses back in 1970), and the movie’s message and style was obviously meant to appeal to campus radicals.

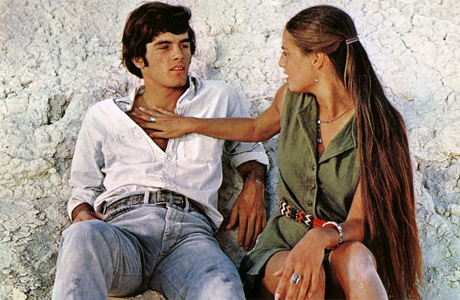

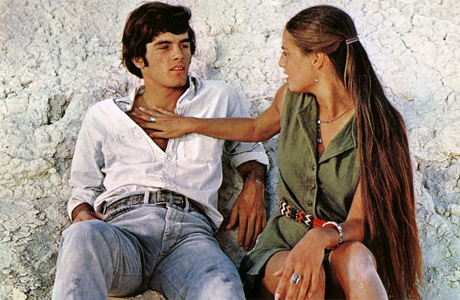

Mark Frechette, star of Zabriskie Point

Zabriskie Point opens with the type of lengthy scene that will be familiar to anyone familiar with counter-culture filmmaking. A bunch of very serious college students sit in a conference room and have a very long conversation about how to best bring about the revolution. All of the white, middle class students argue for petitions, manifestos, and civil disobedience. A black woman with a gigantic afro replies that all of the white students are phonies who aren’t truly committed to the revolution. Some of the students cheer. Some of the students boo. The meeting goes on for an eternity and, for the most part, it served to remind me of why I could never stand hanging out with any of the student activists back at the University of North Texas.

Yet, at the same time, it’s an effective scene because it’s one of the rare moments in the film that feels authentic. For the most part, Antonioni cast this film with nonactors. (Though apparently — just like in Getting Straight — a young Harrison Ford can be seen in the background of some of the scenes.) Watching the opening, I got the feeling that I was experiencing what a political gathering in the 70s was truly like. And, by the end of it, I was happy to have been born long after the 70s were over.

The scene ends when a student named Mark announces that he’s prepared to die for the revolution and then walks out of the meeting. Mark proceeds to drop out of school, buy a lot of guns, and set up an apartment safe house. When he gets arrested at a protest, Mark gives his name as “Karl Marx,” which the booking officer proceeds to spell as “Carl Marx.” Eventually, Mark ends up shooting a police officer. (Or maybe he didn’t — the film is deliberately vague about whether Mark actually fired his gun or if the officer was shot by somebody else.) He then steals an airplane, flies out to the desert, and meets Daria.

Mark and Daria

In the film’s most famous scene, Daria and Mark walk around the desert and talk about — well, nothing in particular. One of the most frequent criticisms of Zabriskie Point is that neither Mark nor Daria were particularly good actors and that’s certainly true. However, that’s only a problem if you assume that Antonioni means for you to view these characters as individuals. As becomes clear during their desert walk, Mark and Daria are meant to be archetypes. Mark Frechette and Daria Halperin may have been terrible actors but they had the right look and they had the right attitude. You may not care about them as individuals but Mark and Daria work perfectly as symbols for alienation. Mark and Daria stand in for everyone who has reached the point where they have to decide whether to join the establishment (represented by Lee Allen and the university) or whether to overthrow it. In the scenes in the desert, Antonioni presents Mark and Daria less as being people and more as being parts of the American landscape, as permanent as the mountains that surround them.

Mark and Daria end up making love in the middle of the desert and, as they have sex, they are suddenly surrounded by hundreds of other hippie couples having sex and it all becomes one big orgy in the middle of Death Valley. And yes, this scene is totally over-the-top, pretentious, and ludicrous but yet, how can you condemn something so gloriously silly?

Orgy in the desert

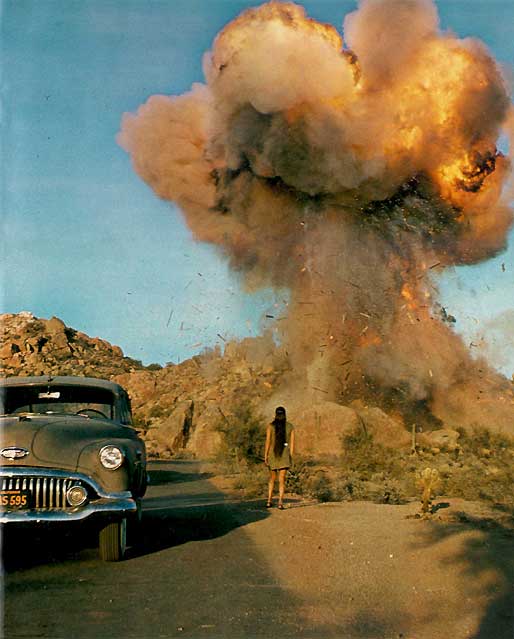

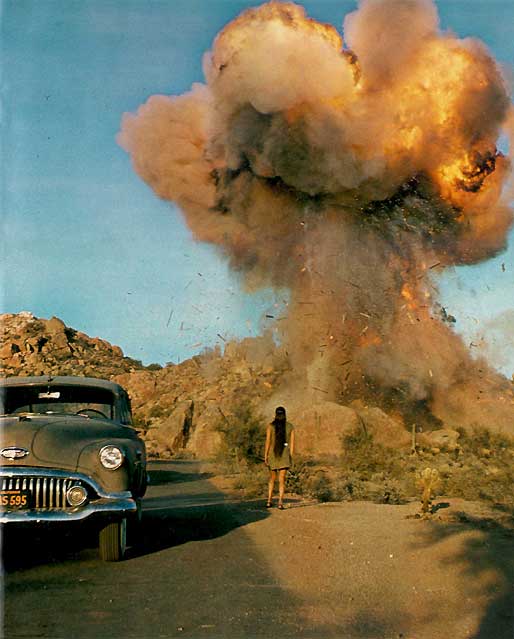

Anyway, after the orgy, Mark and Daria paint his plane and then go their separate ways. Mark tries to return the plane. Daria stares at a house in the mountains and imagines it exploding over and over again.

Zabriskie Point is an interesting misfire. Michelangelo Antonioni (who is best known for directing the classic Blow-Up) originally intended for the film to end with an airplane skywriting “Fuck you, America.” However, MGM made him cut that from the film. That Antonioni meant for this film to be an attack on America is pretty obvious. Antonioni, after all, was a committed Marxist and the film goes out of its way to try to present businessman Lee Allen as being the epitome of capitalist evil. (Unfortunately, Rod Taylor is such a likable actor that I know, if I had to make a choice between the two, I’d rather spend a day with Lee Allen than Mark Frechette).

Rod Taylor as Lee Allen

However, at the same time, Antonioni appears to have been fascinated and confused by the material excesses of America as well. In the first half of the film, as Mark walks through the small town setting, the camera lingers on the billboards that dot the landscape and, as a result, those billboards take on a beauty of their very own. Even when Daria is walking through Lee Allen’s mansion, the camera can’t help but linger over every opulent detail, almost as if it can’t decide whether it is seeking to condemn or celebrate. In many ways, Zabriskie Point reminded me of Lars Von Trier’s Dogville. Both films attempts to condemn America just to end up accidentally celebrating it.

Celebrating America While Condemning It

Zabriskie Point may not be a good film but it’s an endlessly fascinating and visually beautiful one. If nothing else, it serves as a record of the time when it was made. And, as such, it deserves better than to be dismissed as one of the worst.

Boom