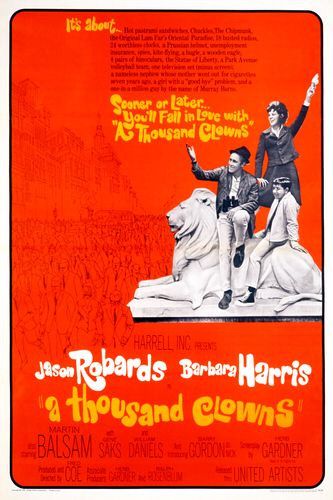

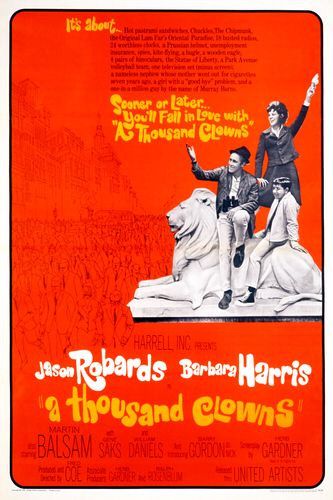

The 1965 film A Thousand Clowns is one of the most annoying films to ever be nominated for best picture.

I know what you’re thinking.

Really, Lisa — even more annoying than Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close?

Well, no. No movie is as annoying as Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. In fact, even if it didn’t particularly work for me, I can kind of understand why A Thousand Clowns was apparently a box office success in 1965. To be honest, part of my annoyance with the film comes from the fact that not only can I understand why other people would love it but I probably would have loved it if I had been alive to see it when it was first released. A Thousand Clowns isn’t an awful film but to say that it has not aged well is a bit of an understatement.

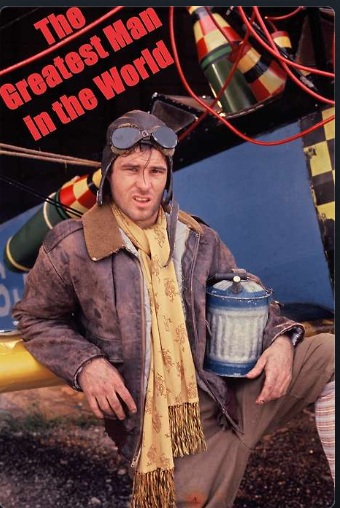

It tells the story of Murray Burns (Jason Robards). Murray lives in a cluttered New York apartment with his 12 year-old nephew, Nick (Barry Gordon). Seven years ago, Nick’s mother abandoned him with Murray. Murray views Nick as being his own son. Nick worships his Uncle Murray. Murray randomly sings Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby. Nick picks up on the habit and is soon wandering around and humming Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby. By the end of A Thousand Clowns you will be so freaking sick of hearing that song. (Fortunately, Murray never sings Send In The Clowns. The film dodged a bullet on that one.)

Murray’s a nonconformist, the type who starts his day by standing outside and mocking everyone who is getting ready to go to work. Murray used to have a job. He was a TV writer. He wrote jokes for a detestable entertainer known as Chuckles The Chipmunk (played by noted Broadway director Gene Saks). Five months ago, Murray quit his job. He’s now unemployed and proud of it. He swears that he will never again sacrifice his freedom for a paycheck. He raises Nick to take the same attitude towards life.

Two social workers, Albert (Williams Daniels) and Sandra (Barbara Harris), show up at Murray’s apartment. They say that unless Murray gets a job and proves that he’s a good guardian, Nick will be taken away from him. Murray explains that he’s a nonconformist and that he’s raising Nick to reject anything conventional. Albert is offended. Sandra is charmed. Soon, Sandra and Murray are going for bike rides through New York City. Murray sings Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby some more…

And it all sounds good but the film just didn’t work for me. First off, I’ve actually experienced what it’s like to grow up with a frequently unemployed father and, sorry, it’s not all studio apartments and cheerful trips to Central Park. Secondly, A Thousand Clown‘s message of carpe diem might have seemed groundbreaking in 1965 but today, it just seems like a cliché. I mean, everyone claims to be a nonconformist today.

Watching the film, it’s hard not to feel that it doesn’t really play fair. It’s easy for the film to always portray Murray as being enlightened when the only people who ever disagree with him are humorless strawmen. Albert is a self-righteous prig while Chuckles The Chipmunk is a heavy-handed caricature, the type of TV star who could only be created by a writer who is resentful that more people are watching TV than reading his latest masterpiece. Martin Balsam appears as Murray’s brother, Arnold, and gets a chance to defend his decision to lead a normal, conventional life. When it comes to the brothers, the film obviously want us to side with Murray but instead, you feel more sympathy for Arnold, largely because Martin Balsam was such an authoritative actor that your natural tendency is to assume that he must know what he’s talking about. It’s interesting to note that it was Balsam, as the voice of mainstream conformity, that won the film’s only Oscar.

Jason Robards was not even nominated, though his performance is often better than the material. He and Barbara Harris have a sweet chemistry, even though Harris is stuck playing a rather demeaning role. (When we first meet Sandra, she is dating Albert and assuming that he’s correct about anything. Then she falls for Murray and assumes that he is the one who is correct about everything. What the film never bothers to really explore is what Sandra herself thinks about anything.) But then you’ve got Barry Gordon, who, in the role of Nick, comes across as being a bratty know-it-all weirdo. Nick is so obnoxious that it undercuts the movie’s claim that Murray deserves to be his guardian.

Also not nominated, despite the film winning a best picture nomination, was the director, Fred Coe. (Nominated in his place were William Wyler for The Collector and Hiroshi Teshigahara for The Woman In The Dunes.) His omission is less surprising than that of Jason Robards. If you didn’t know that A Thousand Clowns was based on a stage play, you’d guess it after watching the first ten minutes of the film. Despite a few shots of Murray and Sandra in New York City, A Thousand Clowns never breaks free of its stage origins. Taking place on largely one set, it feels rather confining for a film meant to celebrate nonconformity.

As I said, I didn’t care much for A Thousand Clowns but I can understand why it was probably a hit with 1965 audiences. Murray’s a transitional figure, standing between the Beats and the Hippies. With America’s confidence shaken by the Kennedy assassination and growing social unrest, I’m sure a lot of people wanted to drop out of society just like Murray. To be honest, a lot of people feel like that right now. I just hope that, if you do decide to follow Murray’s example, you’ll sing something less annoying than Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby.

A Thousand Clowns was nominated for best picture but it lost to a film that Murray probably would have hated, The Sound of Music.