Ah, the 1930s. America was mired in the Great Depression. FDR was plotting to pack the courts. The American public, sick of playing by the rules and getting little in return, began to admire gangsters and outlaws. The horror genre became the new way to vent about societal insecurity. In Europe, leaders were trying to ignore what was happening in Italy, Spain, and Germany. As for the Academy, it was still growing and developing and finding itself. With people flocking to the movies and the promise of an escape from reality, the Academy Awards went from being an afterthought to a major cultural event.

And, of course, the snubs continued.

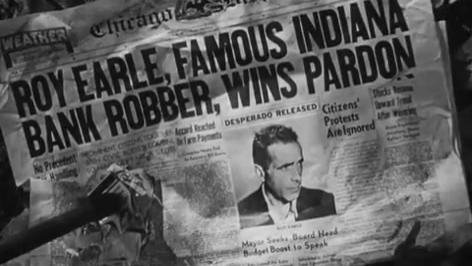

1930 — 1931: Crime Doesn’t Pay For Little Caesar and The Public Enemy

When people think about the 1930s, gangsters are probably one of the first things that come to mind. In the 30s, audiences flocked to movies about tough and streetwise criminals who did what they had to do in order to survive during the Depression. Unfortunately, the Academy was not always as quick to embrace the gangster genre. Though The Public Enemy did pick up a nomination for its screenplay, both it and Little Caesar were largely ignored by the Academy. Not only did the films fail to score nominations for Best Picture but neither James Cagney nor Edward G. Robinson would be nominated for bringing their title characters to life. It’s a crime, I tells ya.

1930 — 1931: Bela Lugosi Is Not Nominated For Best Actor For Dracula

Admittedly, the 1931 version of Dracula is a bit of a creaky affair, one that feels quite stagey to modern audiences. But Bela Lugosi’s performance in the title role holds up well, despite the number of times that it has been parodied. Unfortunately, from the start, the Academy was hesitant about honoring the horror genre.

Frankenstein (1931, dir by James Whale)

1931 — 1932: Boris Karloff Is Not Nominated For Best Actor For Frankenstein

Again, the Academy snubbed an iconic horror star. Not only was Boris Karloff not nominated for Frankenstein but the film itself was not nominated for Best Picture, despite being infinitely better than at least one of the 8 films that were nominated. (That film, by the way, was Bad Girl. When is the last time that anyone watched that one?) In fairness to the Academy, they did honor one horror film at that year’s awards. Fredric March won Best Actor for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Of course, he also tied with Wallace Beery, who was nominated for The Champ. Obviously, the Academy still had to work out its feelings towards the horror genre, a process that continues to this very day.

1932 — 1933: King Kong Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

Oh, poor King Kong. Film audiences loved him but the Academy totally ignored both him and his film. Unfortunately, back in 1933, the Academy had yet to introduce a category for special effects.

1932 — 1933: Duck Soup Is Ignored By The Academy

King Kong was not the only worthy film to be ignored at the 1932-1933 Oscars. The Marx Brothers’s greatest film also went unnominated.

1934: The Scarlet Empress Is Not Nominated For Best Picture

Josef von Sternberg’s surreal historical epic was totally ignored by the Academy. Not only did it miss out on being nominated for Best Picture but the sterling work of Marlene Dietrich and Sam Jaffe was ignored as well. How was the opulent set design ignored? How did it not even pick up a nomination for costume design? My guess is that Paramount chose to promote Cleopatra at expense of The Scarlet Empress. Either the way, the Best Picture Oscar was won by one of my favorite films, It Happened One Night.

1935: Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Are Not Nominated For Top Hat

Top Hat scored a best picture nomination but the film’s two stars went unnominated.

1936: My Man Godfrey Is Nominated For Everything But Best Picture

My Man Godfrey, a classic screwball comedy, was nominated for Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor, Best Supporting Actress, Best Director, and Best Screenplay but somehow, it was not nominated for Best Picture. It’s a shame because My Man Godfrey, along being a very funny movie, is also a film that epitomizes an era. Certainly, it’s far more entertaining today than the film that won Best Picture that year, The Great Ziegfeld. (Interestingly enough, William Powell played the title role in both Godfrey and Ziegfeld.)

1937: Humphrey Bogart Is Not Nominated For Best Supporting Actor in Dead End

Dead End featured one of Bogart’s best gangster roles. As a gangster who returns to his old neighborhood and is rejected by his own mother, Bogart was both menacing and, at times, sympathetic. Like Cagney and Robinson, Bogart definitely deserved a nomination for his portrayal of what it was like to live a life of crime. Unfortunately, Bogart was an actor who was taken for granted for much of his career. It wasn’t until he played Rick Blaine in Casablanca that the Academy would finally nominate him.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938, dir by Michael Curtiz)

1938: Errol Flynn Is Not Nominated For Best Actor In The Adventures of Robin Hood

This is truly one of the more shocking snubs in Academy history. Errol Flynn’s performance as Robin Hood pretty much set the standard for every actor who followed him. Russell Crowe is undoubtedly a better actor than Flynn was but Crowe’s dour interpretation of Robin could in no way compete with the joie de vivre that Flynn brought to the role.

Agree? Disagree? Do you have an Oscar snub that you think is even worse than the 10 listed here? Let us know in the comments!

Up next: 1940s, in which Hollywood joins the war effort and the snubs continue!

Dead End (1937, dir by William Wyler)