Whenever I go to Half-Price Books, I always seem to end up spending most of my time browsing the “nostalgia” section. This is where they keep all of the old paperbacks that were published long before I was born. This is where you can find old romance novels, “for adults only” novels, detective novels, and occasionally you’ll even find mainstream novels that were apparently considered to be quite daring when they were originally released. These novels usually carry cover blurbs that brag about how controversial they are and how they deal with the “real issues of today.”

Whenever I go to Half-Price Books, I always seem to end up spending most of my time browsing the “nostalgia” section. This is where they keep all of the old paperbacks that were published long before I was born. This is where you can find old romance novels, “for adults only” novels, detective novels, and occasionally you’ll even find mainstream novels that were apparently considered to be quite daring when they were originally released. These novels usually carry cover blurbs that brag about how controversial they are and how they deal with the “real issues of today.”

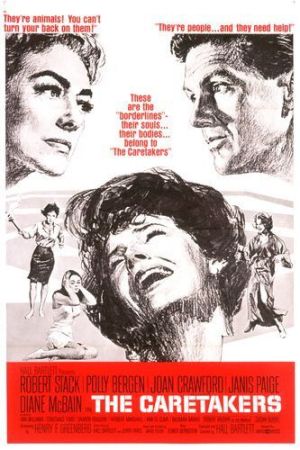

Usually, these novels are pretty silly and over-the-top which is why I always seem to end up buying a lot of them. About a year ago, I bought a novel from 1959. It was by Dariel Telfer and it was called The Caretakers. The cover features a naked woman standing in front of several nurses and doctors. The cover blurb announces that The Caretakers is “A shattering novel about nurses, doctors, and patients in a state hospital where emotions readily explode!” The back cover features a pull quote from Time: “Will shock as well as arouse compassion.”

Now, I have to admit that I have yet to get around to actually reading The Caretakers. However, thanks to TCM, I recently saw the 1963 film version and it’s a film that definitely embraces the melodrama.

How melodramatic is The Caretakers? It’s melodramatic enough that it opens with Lorna Medford (Polly Bergen) stumbling into a movie theater and having a nervous breakdown. Since this film was made in 1963, her mental breakdown is represented by spinning the camera around and getting hyperactive with the zoom lens, all while Bergen shrieks and tears at her hair.

Lorna is sent to a mental hospital, where she meets several other patients and is treated by Dr. MacLeod (Robert Stack), who is a rebel. We know that he’s a rebel because everyone else at the hospital keeps telling him that he’s a rebel and complaining about his use of radical use of group therapy. Under Dr. MacLeod’s guidance, Lorna reveals that she hasn’t gotten over the tragic death of her child.

As the film progresses, Lorna gets to know the rest of the patients. They’re a mixed bunch, all played by actresses who clearly saw this as their chance to pick up an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress and were determined to make as big an impression as possible. For instance, Barbara Barrie plays Edna, who never speaks but who does enjoy setting fires and who, whenever she’s feeling persecuted, poses as if she’s hanging from a cross. And then there’s grandmotherly Irene (Ellen Corby), who is supposed to be the nice one but always looks like she’s on the verge of very sweetly shoving a pair of knitting needles into someone’s eyes.

However, my favorite patient was the cynical Marion (Janis Paige), precisely because she was so cynical and, as a result, she got all the best lines. Marion is a former prostitute who now hates all men and Paige has a lot of fun playing the role. Whenever Paige is giving one of her long, angry monologues, she practically grabs the film and refuses to let it go.

And then, of course, there’s Joan Crawford. Crawford doesn’t play a patient. Instead, she’s the head nurse and she doesn’t approve of Dr. MacLeod’s methods. Crawford announces early on that she’s been attacked by a patient in the past and her main concern is protecting her staff. She teaches a self-defense class. If you’ve ever wanted to see a middle-aged Joan Crawford flip someone over, The Caretakers is a film to watch.

And that’s The Caretakers for you. It’s one of those films that takes itself so seriously that it becomes humorous despite itself. As a result, the film is a lot of unintentional fun.

And who knows?

Maybe someday, I’ll get around to reading the book!