Thanks to TCM’s 31 Days of Oscar, I now have several movies on my DVR that I need to watch over the upcoming month. Don’t get me wrong — I’m not complaining. I’m always happy to have any reason to discover (or perhaps even rediscover) a movie. And, being an Oscar junkie, I especially enjoy the opportunity to watch the movies that were nominated in the past and compare them to the movies that have been nominated more recently.

Thanks to TCM’s 31 Days of Oscar, I now have several movies on my DVR that I need to watch over the upcoming month. Don’t get me wrong — I’m not complaining. I’m always happy to have any reason to discover (or perhaps even rediscover) a movie. And, being an Oscar junkie, I especially enjoy the opportunity to watch the movies that were nominated in the past and compare them to the movies that have been nominated more recently.

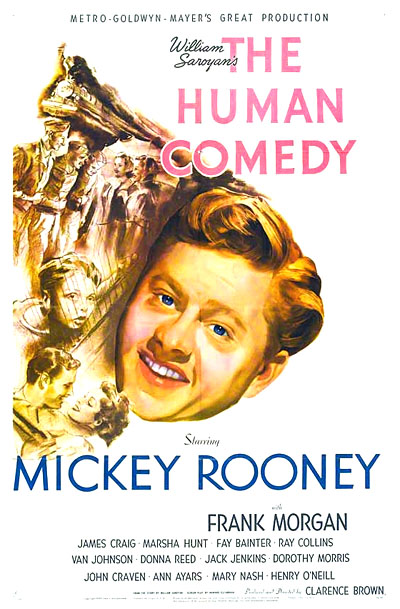

For instance, tonight, I watched The Human Comedy, a film from 1943. Along with being a considerable box office success, The Human Comedy won on Oscar (for Best Story) and was nominated for four others: picture, director (Clarence Brown), actor (Mickey Rooney), and black-and-white cinematography. The Human Comedy was quite a success in 1943 but I imagine that, if it were released today, it would probably be dismissed as being too sentimental. Watching The Human Comedy today is something of a strange experience because it is a film without a hint of cynicism. It deals with serious issues but it does so in such a positive and optimistic manner that, for those of us who are used to films like The Big Short and Spotlight, a bit of an attitude adjustment is necessary before watching.

And yet that doesn’t mean that The Human Comedy is a bad film. In fact, I quite enjoyed it. The Human Comedy is a time capsule, a chance to look into the past. It also features a great central performance, one that was quite rightfully nominated for an Oscar. As I watched Mickey Rooney in this film, I started to feel guilty for some of the comments I made when I reviewed Mickey in The Manipulator last October.

The Human Comedy opens with an overhead shot of the small town of Ithaca, California. The face of Mr. McCauley (Ray Collins, who you’ll recognize immediately as Boss Jim Gettys from Citizen Kane) suddenly appears in the clouds. Mr. McCauley explains that he’s dead and he’s been dead for quite some time. But he loves Ithaca so much that his spirit still hangs around the town and keeps an eye on his family. Somehow, the use of dead Mr. McCauley as the film’s narrator comes across as being both creepy and silly.

But no sooner has Mr. McCauley stopped extolling the virtues of small town life than we see his youngest song, 7 year-old Ulysseus (Jack Jenkins), standing beside a railroad track and watching a train as it rumbles by. Sitting on the cars are a combination of soldiers and hobos. Ulysseus waves at some of the soldiers but none of them wave back. Finally, one man waves back at Ulysseus and calls out, “Going home, I’m going home!” It’s a beautifully shot scene, one that verges on the surreal.

That opening pretty much epitomizes the experience of watching The Human Comedy. For every overly sentimental moment, there will be an effective one that will take you by surprise. The end result may be uneven but it’s still undeniably effective.

The majority of the film deals with Homer McCauley (Mickey Rooney). Homer may still be in high school but, with his older brother, Marcus (Van Johnson), serving overseas and his father dead, Homer is also the man of the house. Homer not only serves as a role model for Ulysseus but he’s also protector for his sister, Bess (Donna Reed). (At one point in the film, she gets hit on by three soldiers on leave. One of them is played by none other than Robert Mitchum.) In order to bring in extra money for the household, Homer gets a job delivering telegrams.

In between scenes of Homer in Ithaca, we get oddly dream-like scenes of Marcus and his army buddies hanging out. Marcus spends all of his time talking about how much he loves Ithaca and how he can’t wait for the war to be over so he can return home. One of his fellow soldiers says, “I almost feel like Ithaca is my hometown, too.” Marcus promises him that they’ll all visit Ithaca. As soon as the war is over…

With World War II raging, Homer’s job largely consists of delivering death notices (and the occasional singing telegram, as well). Telegraph operator Willie Grogan (Frank Morgan) deals with the burden of having to transcribe bad news by drinking. Homer, meanwhile, tries to do his job with compassion and dignity but one day, he has to deliver a telegram to his own house…

The Human Comedy is an episodic film, full of vignettes of life in Ithaca and Homer growing up. There’s quite a few subplots (along with a lot of speeches about how America is the best country in the world) but, for the most part, the film works best when it concentrates on Homer and Mickey Rooney’s surprisingly subdued lead performance. By today’s standards, it may seem a bit predictable and overly sentimental but it’s also so achingly sincere that you can’t help but appreciate it.

The Human Comedy was nominated for best picture but it lost to a somewhat more cynical film about life during World War II, Casablanca.