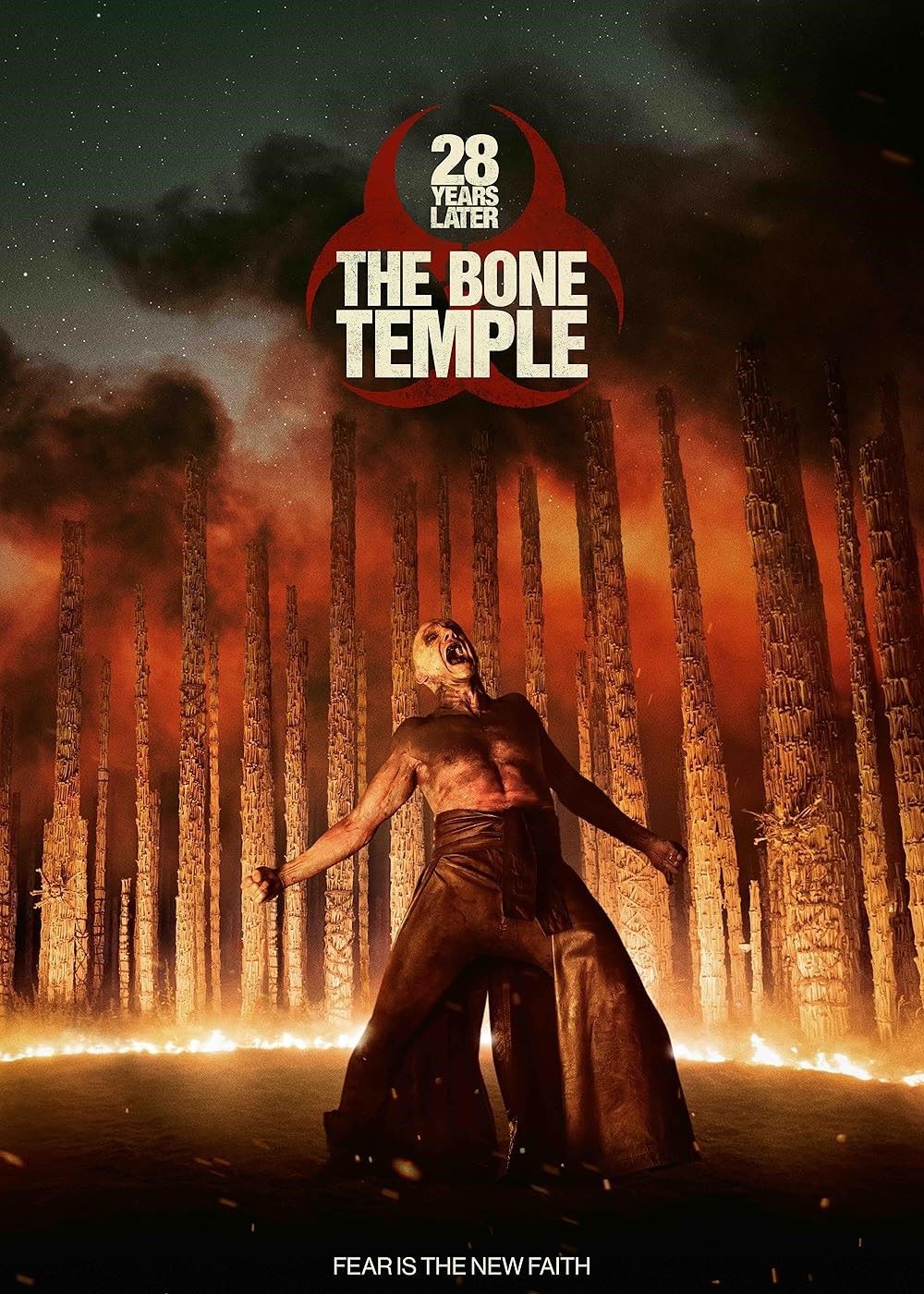

“Every skull is a set of thoughts. These sockets saw and these jaws spoke and swallowed. This is a monument to them. A temple.” — Dr. Ian Kelson

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple crashes into 2026 with the force of a Rage-infected sprint, claiming its spot as one of the year’s top films right out of the gate, flaws and all. Directed by Nia DaCosta, the film continues to showcase her evolving command as a filmmaker, building directly on the promise of her 2025 character study Hedda, where she dissected emotional isolation with surgical precision and atmospheric tension. Where The Marvels in 2023 felt like a worthy attempt hampered by a screenplay that couldn’t decide on a tone—swinging between quippy banter and high-stakes drama while beholden to the cinematic universe’s endless interconnections—The Bone Temple unleashes DaCosta at full throttle, free from franchise baggage to craft a horror epic that’s visually poetic, thematically fearless, and rhythmically assured.

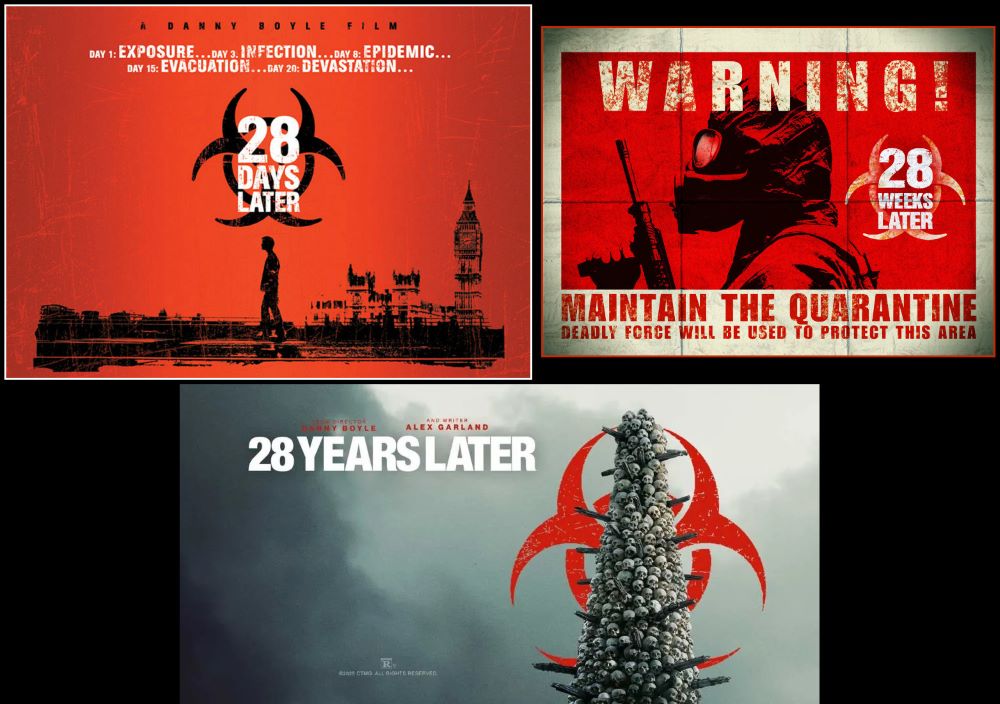

Yeah, it revels in bleakness that can border on exhausting, and its structure wanders more than it charges forward, but those imperfections only underscore how fiercely original and alive it feels compared to the rote horror sequels we’re usually fed. Decades past the initial outbreak that defined 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later, the apocalypse here isn’t a fresh crisis anymore—it’s infrastructure, a grim new normal etched into the landscape. Survivors haven’t rebuilt so much as repurposed the ruins, carving out rituals and monuments that say as much about lingering trauma as they do about adaptation. The Rage virus still turns people into feral killers, ripping through flesh in those signature bursts of speed and savagery, but the infected have evolved in intriguing ways that deepen the world’s mythology without overshadowing the human core. The spotlight swings to human extremes: towering bone architectures raised as memorials, nomadic gangs treating murder like liturgy, and lone figures wrestling with whether dignity even matters when bodies pile up unmarked. This pivot lets the film breathe in ways the earlier entries couldn’t, expanding a zombie-adjacent thriller into something folk-horrific and introspective.

Dr. Ian Kelson embodies that shift, and Ralph Fiennes delivers what might be his meatiest role in years—a reclusive physician-architect whose Bone Temple dominates the story like a character itself, adding a profound level of tragic humanity that stands in stark, poignant contrast to the nihilistic worldview of Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal and his blindly devoted followers. Picture spires of meticulously arranged skulls and femurs, bleached white against misty Scottish skies, lit at night like profane altars: it’s production design that hits you visually first, then sinks in thematically as Kelson’s obsession with cataloging the dead. Fiennes plays him not as a villain or eccentric, but as a man fraying at the edges—tender when easing a dying woman’s passage (Spike’s mother, in a flashback that sets the whole narrative in motion), ruthless in his logic about preserving memory over sentiment. “Every skull is a set of thoughts,” he murmurs in one standout line, sockets staring empty, jaws frozen mid-word—a perfect encapsulation of the film’s meditation on legacy amid oblivion. Those quiet scenes, where Kelson debates ethics with survivors or observes the infected Samson with clinical curiosity shading into something paternal, ground the movie’s wilder swings and prove Fiennes can carry horror on sheer presence alone.

Spike, our entry point into this madness, carries scars from that childhood brush with the Temple and his mother’s end, propelling him toward Jimmy Crystal’s orbit like fate’s cruel magnet. He’s no square-jawed lead; he’s reactive, watchful, hardening through trials that test his humanity without fully erasing it. That arc collides with Jimmy’s cult—a roving pack of devotees renamed his “seven fingers,” all aping the leader’s bleach-blond hair, loud tracksuits, and flashy trinkets in a uniformity that’s both comic and chilling. Jack O’Connell chews the scenery as Jimmy, a pint-sized prophet whose charisma masks profound damage: twitchy grins, boyish rants blending kids’ TV catchphrases with fire-and-brimstone, devotion to his “Old Nick” devil figure turning every kill into theater. The Savile visual parallels—those garish outfits evoking the real-life abuser’s predatory fame—add a layer of cultural poison, implying charisma survives apocalypse by mutating into something even uglier, with institutions gone but the hunger for idols intact. O’Connell makes Jimmy magnetic and monstrous, a performance that elevates the cult from trope to tragedy.

If the film’s greatness shines through performances and visuals, its violence tests that shine—deliberately, one suspects. Infected attacks deliver franchise-expected chaos: heads torn free, eyes clawed out, bodies pulped in handheld frenzy. But Jimmy’s rituals amp the sadism—knife duels extended into endurance ordeals, flayings half-glimpsed but fully heard, victims’ pleas dragging until empathy fatigues. It’s grueling, sometimes overlong, risking audience burnout, yet it serves the theme: in a Rage world, human-inflicted torment outlasts viral rage because it feeds on belief. DaCosta pulls punches visually (smart cuts, shadows over gore) but lingers on emotional fallout, making cruelty feel earned rather than exploited— a maturation from The Marvels‘ tonal whiplash into controlled, purposeful discomfort. Counterpoints pierce through: Jimmy Ink’s furtive kindnesses toward Spike, Ian and Samson’s drug-hazy field dances blurring monster and man, fragments of backstory humanizing even Jimmy’s frenzy. These glimmers don’t redeem the world—they make its harshness sting deeper, proving flickers of connection persist as defiant accidents.

Technically, the film flexes non-stop, with DaCosta’s post-Hedda assurance evident in every frame. Anthony Dod Mantle’s cinematography weds gritty digital shakes to sweeping drone shots, turning Highlands into deceptive idylls ruptured by whip-pans and flame flares. Sound design hums with menace—whistling winds masking howls, train rumbles underscoring rituals, screams echoing into silence for maximum unease. Editing mirrors the narrative’s spiral: episodic loops around Spike’s hardening, Ian’s doubt, Jimmy’s collapse, eschewing linear escalation for dream-logic dread that suits a “settled” apocalypse. The Temple centerpiece ritual explodes into metal-thrash worship, cultists moshing amid pyres—a grotesque stadium parody where faith meets fandom in blood-soaked ecstasy. Even the score pulses with restraint, letting ambient horror fill gaps better than bombast ever could.

Tonally, it juggles masterfully: tender Kelson vignettes abut cult carnage, philosophical riffs on atheism versus delusion frame gore-fests, folk-horror monuments clash with infection thriller roots. Themes of faith-as-coping, grief-as-art, ideology’s pitfalls land without preaching—Kelson’s secular duty versus Jimmy’s ecstatic nihilism debates through action, not monologue. The ending circles back to series emotional cores (survival’s cost, hope’s fragility) while forging ahead, teasing Spike’s grim purpose without cheap uplift.

Flaws? The runtime sags in cult stretches, bleakness borders masochistic, sprawl might frustrate plot-chasers. But these are risks of ambition, not laziness—choices that make triumphs (Fiennes’ gravitas, O’Connell’s feral spark, visuals’ poetry) land harder, all under DaCosta’s steady hand that Hedda honed and The Marvels tested. In January 2026, amid safe genre retreads, The Bone Temple towers: a sequel philosophically dense, actor-propelled, unafraid to wound deeply then whisper mercy. It hurts because it sees us clearly—craving structure in chaos, building temples from bones, real or imagined. One of the year’s best, period, for daring to evolve rather than echo.