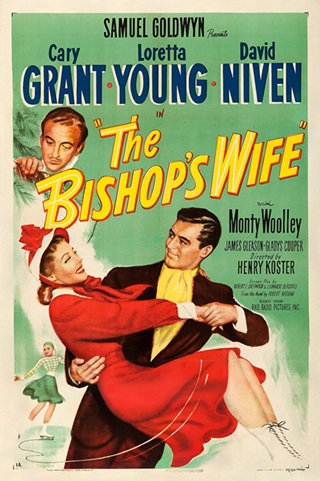

In 1947’s The Bishop’s Wife, Cary Grant stars as Dudley.

We first see Dudley walking down the snow-covered streets of a city that is preparing for Christmas. He watches Julia Broughman (Loretta Young), the wife of the local Anglican bishop. He stops to talk to Prof. Wutheridge (Monty Woolly), a secular humanist who is close to Julia and her husband, despite being irreligious himself. Dudley seems to know all about the professor, even though the professor is not sure who he is. The professor mentions that he was fired from a university because he was considered to be a “radical,” even though he has no interest in politics. The professor says that the town’s church has seen better days, especially since the Bishop is more interested in raising money from the rich to build a grand new cathedral than actually meeting with the poor who need help.

The last person that Dudley visits is Bishop Henry Broughman (David Niven). Dudley reveals to Henry that he’s angel and that he’s come in response to Henry’s prayers. Henry has been frustrated in his attempts to raise money for a new cathedral. Dudley has come to provide guidance.

With only the Bishop knowing the truth about Dudley, Dudley becomes a houseguest of the Broughmans. The Bishop has become so obsessed with his new cathedral that he’s not only been neglecting his diocese but also his family. While Dudley tries to show Henry what’s really important, he also helps Julia and her daughter Debby (Karolyn Grimes) to fit in with the neighborhood. (Bobby Anderson, who played the young George Bailey in It’s A Wonderful Life, makes an appearance as a boy having a snowball fight who says that Debby can’t play because no one wants to risk hitting a bishop’s daughter with a snowball.) The Bishop becomes jealous of Dudley and perhaps he should be as Dudley finds himself falling in love with Julia and considering not moving on to his next assignment.

(And now we know where Highway to Heaven got the inspiration for 75% of its episodes….)

The Bishop’s Wife is an enjoyable film, one that is full of not just Christmas imagery but also the Christmas spirit as well. The Bishop finally realizes that his planned cathedral is more of a gift to his ego than to the men and women who look to him for guidance and comfort in difficult times. David Niven is, as always, likable even when his character is acting like a jerk. That said, this is pretty much Cary Grant’s show from the start. Suave, charming, and gently humorous, Grant joins Claude Rains and Henry Travers in the ranks of great cinematic angels. Never mind that Grant’s character is a bit pushy and has his own crisis of faith. From the minute that Grant appears, we know that he’ll know exactly the right way to answer Henry’s prayers.

Cary Grant was not nominated for Best Actor for his performance here. Undoubtedly, this was another case of Grant making it all look so easy that the Academy failed to realize just how good of a performance he gave. Interestingly enough, The Bishop’s Wife was one of two Christmas films nominated for Best Picture that year, along with Miracle on 34th Street. Both films lost to Gentleman’s Agreement.