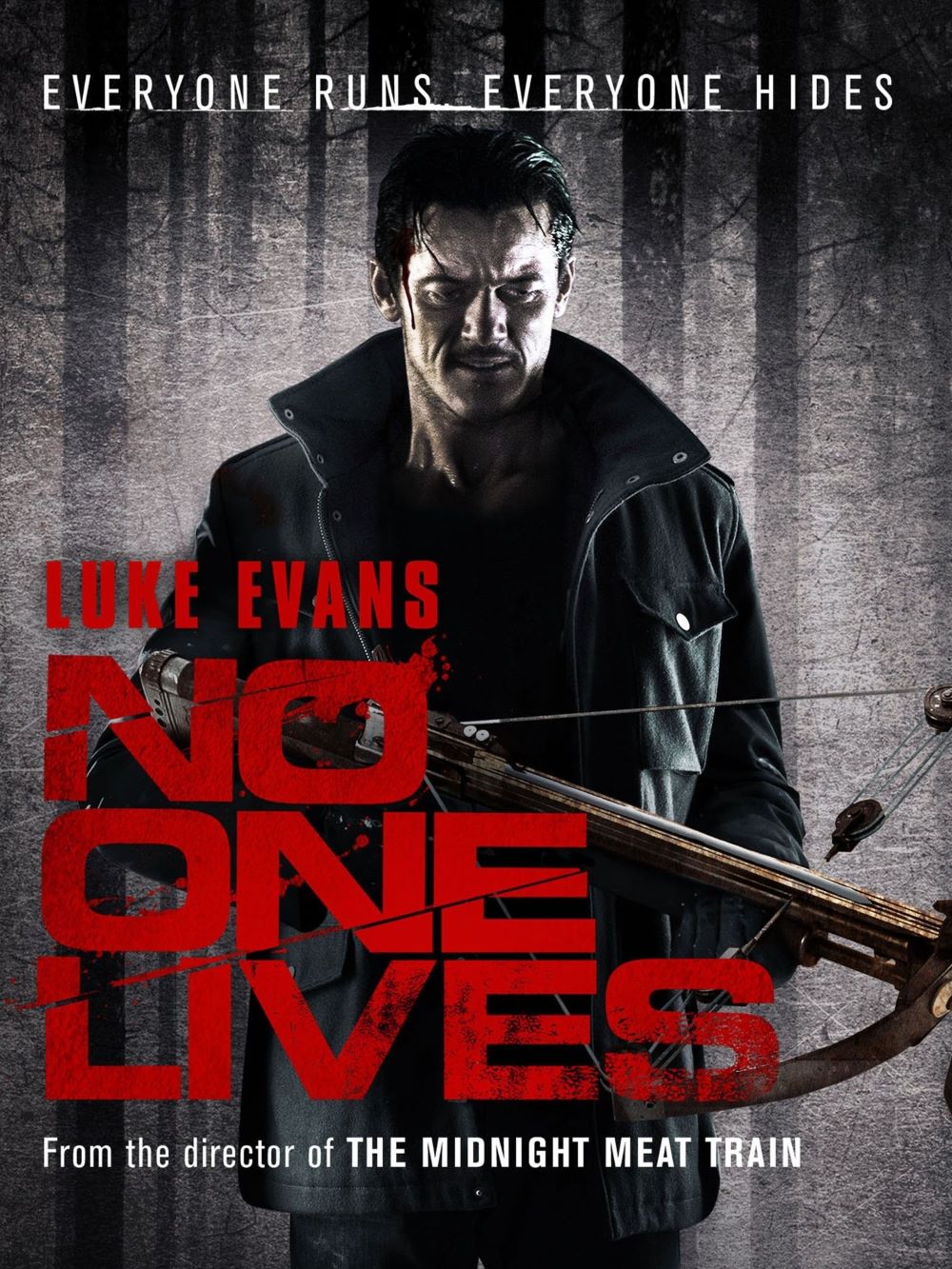

Ryuhei Kitamura’s 2012 horror film No One Lives is a gritty, brutal revenge slasher that doesn’t aim for subtlety or depth but delivers a fast-paced, high-gore thrill ride. The story follows a couple traveling cross-country who are kidnapped by a ruthless gang, only for the man to reveal himself as a deadly predator on a violent rampage. Luke Evans, playing the mysterious and merciless Driver, leads the film with a performance that blends cold calculation and terrifying violence, keeping viewers glued to the screen.

What makes No One Lives stand out is how it leans heavily into its grindhouse and exploitation roots, which proves both advantageous and limiting. The film fully embraces the hallmarks of grindhouse cinema—fast pacing, gritty visuals, excessive gore, and an amoral story stripped down to revenge-fueled violence. This raw, unapologetic approach results in an intense, no-holds-barred experience that will satisfy fans of exploitation and grindhouse styles. The practical effects are impressively executed, with creative and shocking kills that maintain impact without descending into the ridiculous. This dedication to grindhouse aesthetics gives the film a charged energy and a cult appeal, making it a pulpy, heart-pounding experience for viewers who appreciate that sleazy, nihilistic flavor.

However, the grindhouse influence also shapes the film’s limitations. The focus on spectacle and shock means character development and thematic depth take a back seat, making the story feel thin and the characters largely unrelatable except as violent archetypes. Dialogue at times drifts toward camp, and some acting choices can feel a bit amateurish, which may pull some viewers out of the otherwise tense atmosphere. The film’s relentless brutality and amoral tone also create a polarizing effect; it’s unapologetically harsh and violent, which fits the exploitation tradition, but it’s not for everyone. Those expecting traditional horror with complex narratives might find the experience shallow and exhausting.

Luke Evans’s Driver is a compelling anti-hero/monster hybrid, a character who dominates the film with his cold efficiency and unpredictable savagery. The other characters—mostly the gang members—serve as fodder for the film’s violent set pieces, with minimal background or sympathy. This suits the film’s grindhouse style, where depth is often sacrificed for thrills and shock value. The script cleverly keeps some mystery around Driver, maintaining suspense about his origins and intentions, which helps to sustain interest amid the unrelenting carnage.

The film’s grindhouse and exploitation roots also explain its tone and style: it revels in zaniness and excess, the gore is gratuitous but skillfully done, and the revenges feel morally ambiguous and raw. The film doesn’t try to justify or soften its violence; it embraces the lawlessness and nihilism typical of exploitation cinema. While this results in a tight, entertaining 86-minute rush of thrills, it also means the film lacks subtlety or emotional resonance. The style is both a badge of authenticity for genre fans and a barrier to wider appeal.

No One Lives offers a high-energy, blood-soaked horror experience that fully embraces its grindhouse and exploitation influences. It is crafted with a strong focus on unapologetic violence, tight pacing, and a captivating anti-hero in Luke Evans’s Driver. This stylized approach gives the film its raw, relentless intensity that fans of exploitation cinema will appreciate. However, this allegiance to grindhouse aesthetics also means the film prioritizes style and spectacle over emotional depth and narrative complexity. While the movie is an engaging and brutal thrill ride for those who enjoy extreme horror, its minimal character development and abrasive tone might feel one-dimensional or grating for viewers seeking more meaningful storytelling. Overall, it succeeds as a wild, gritty exploitation flick but doesn’t aim to be more than that, making it ideal for audiences who like their horror unrefined and full throttle.

Previous Guilty Pleasures

- Half-Baked

- Save The Last Dance

- Every Rose Has Its Thorns

- The Jeremy Kyle Show

- Invasion USA

- The Golden Child

- Final Destination 2

- Paparazzi

- The Principal

- The Substitute

- Terror In The Family

- Pandorum

- Lambada

- Fear

- Cocktail

- Keep Off The Grass

- Girls, Girls, Girls

- Class

- Tart

- King Kong vs. Godzilla

- Hawk the Slayer

- Battle Beyond the Stars

- Meridian

- Walk of Shame

- From Justin To Kelly

- Project Greenlight

- Sex Decoy: Love Stings

- Swimfan

- On the Line

- Wolfen

- Hail Caesar!

- It’s So Cold In The D

- In the Mix

- Healed By Grace

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Legend of Billie Jean

- Death Wish

- Shipping Wars

- Ghost Whisperer

- Parking Wars

- The Dead Are After Me

- Harper’s Island

- The Resurrection of Gavin Stone

- Paranormal State

- Utopia

- Bar Rescue

- The Powers of Matthew Star

- Spiker

- Heavenly Bodies

- Maid in Manhattan

- Rage and Honor

- Saved By The Bell 3. 21 “No Hope With Dope”

- Happy Gilmore

- Solarbabies

- The Dawn of Correction

- Once You Understand

- The Voyeurs

- Robot Jox

- Teen Wolf

- The Running Man

- Double Dragon

- Backtrack

- Julie and Jack

- Karate Warrior

- Invaders From Mars

- Cloverfield

- Aerobicide

- Blood Harvest

- Shocking Dark

- Face The Truth

- Submerged

- The Canyons

- Days of Thunder

- Van Helsing

- The Night Comes for Us

- Code of Silence

- Captain Ron

- Armageddon

- Kate’s Secret

- Point Break

- The Replacements

- The Shadow

- Meteor

- Last Action Hero

- Attack of the Killer Tomatoes

- The Horror at 37,000 Feet

- The ‘Burbs

- Lifeforce

- Highschool of the Dead

- Ice Station Zebra