“Sometimes I wonder… will God ever forgive us for what we’ve done to each other? Then I look around and I realize, God left this place a long time ago.” — Danny Archer

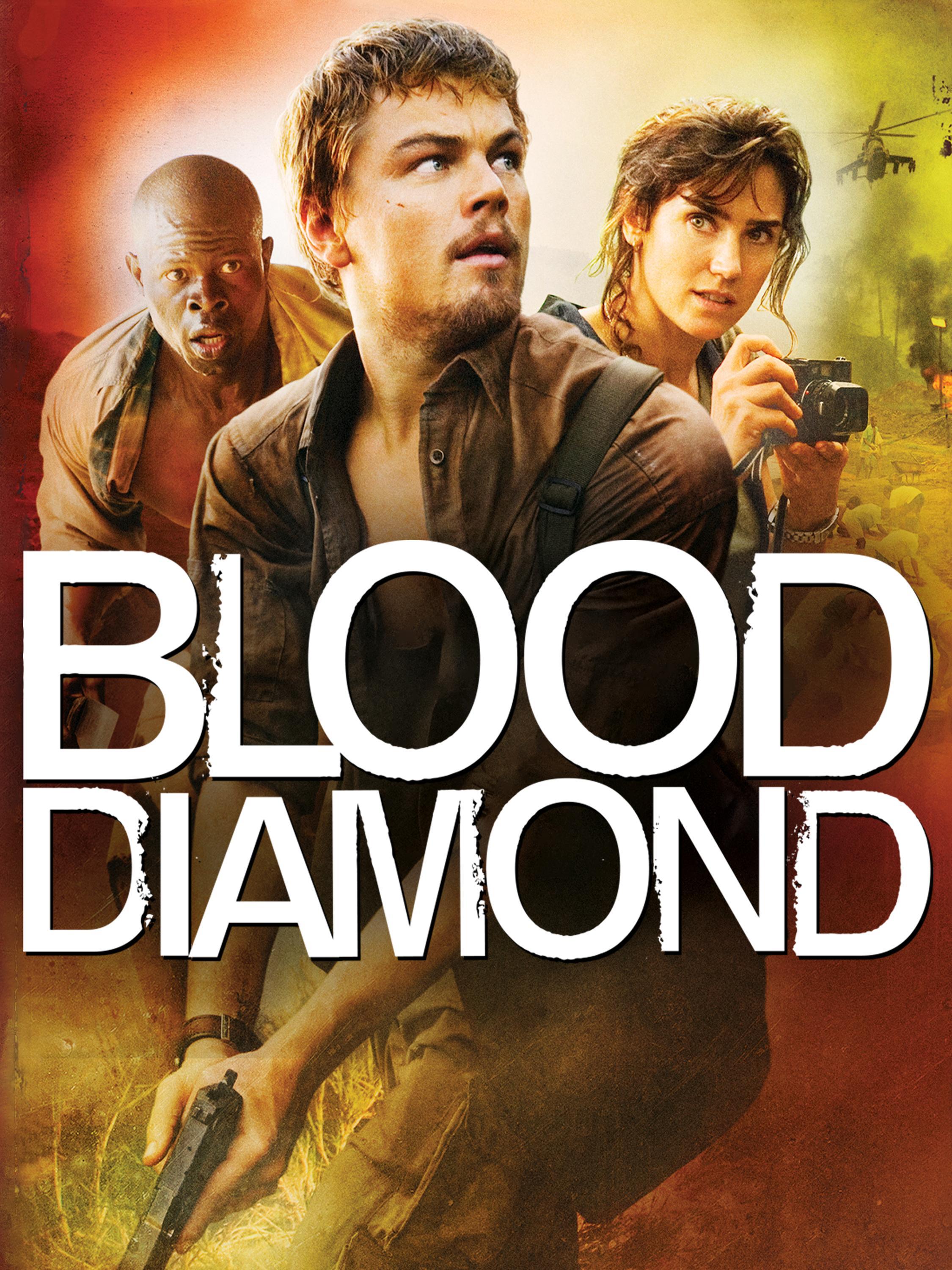

Edward Zwick’s 2006 film Blood Diamond is one of those big Hollywood productions that tries to be both a gritty, globe-trotting thriller and a politically conscious indictment of the diamond trade’s role in African civil wars. Set in Sierra Leone during the 1990s, it stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Danny Archer, a Rhodesian mercenary and diamond smuggler, and Djimon Hounsou as Solomon Vandy, a fisherman torn from his family by rebels and forced into brutal diamond mining. Rounding out the leads is Jennifer Connelly as Maddy Bowen, a tenacious reporter determined to expose the atrocities fueling the global supply of conflict diamonds. The film is ambitious, harrowing, and, at times, as slickly entertaining as it is bluntly didactic. But like many socially minded blockbusters, it walks a tightrope between genuine drama and Hollywood sensationalism.

The story kicks off with a bang—literally—as Solomon’s village is raided by Revolutionary United Front militants, a moment that quickly plunges the viewer into Sierra Leone’s chaotic civil war. Solomon’s family is fragmented: he ends up a slave at a rebel-run mining camp, his son is eventually brainwashed into a child soldier, and his wife flees for safety. Meanwhile, DiCaprio’s Archer lands in jail after a failed smuggling run—which sets the two men on a collision course. Archer learns of Solomon’s discovery of an enormous, rare pink diamond—a stone that could mean escape or redemption for both men but is a magnet for greed, violence, and compromise. Their uneasy partnership with Maddy Bowen, who’s chasing a story, adds layers as their individual motives collide and evolve.

The movie doesn’t shy away from illustrating the devastating effects of the diamond trade—child soldiers, forced labor, mass displacement, and political corruption. While most of the on-screen violence is handled to maximize emotional punch, it never lets the viewer forget the real-world stakes of the Blood Diamond narrative. The film ultimately points viewers toward the establishment of the Kimberley Process—a set of international regulations designed to combat the illicit diamond trade.

A lot of the film’s emotional weight lands on DiCaprio and Hounsou, and for good reason. Leonardo DiCaprio nabs the complex role of Danny Archer with a layered performance and goes the extra mile by working hard on the Zimbabwean (Rhodesian) accent. While accents in film can be divisive, DiCaprio immersed himself deeply, working with dialect coaches and spending time with people from the region to best capture the regional nuances. Although some viewers and critics felt the accent was uneven or shifted at points, many others praised him for nailing this challenging and rare dialect. For an American actor to convincingly embody a mercenary with roots in that part of the world is no small feat. DiCaprio’s commitment brings credibility to Archer’s character, who is morally ambiguous but immensely human.

Djimon Hounsou, playing Solomon Vandy, serves as the emotional core and grounding presence of the film. His portrayal of a man torn apart by civil war, who fights desperately to reclaim his family, is heartbreaking and physically compelling. Their scenes together create genuine tension, as trust is both scarce and necessary for survival. Jennifer Connelly’s Maddy Bowen, while less fleshed out, brings determination and serves as the moral compass driving the film’s exposé of conflict diamonds.

Director Edward Zwick has a way of blending spectacle with raw storytelling. The action sequences, especially the firefights and escapes, feel intense and immersive. The cinematography captures the lush, dangerous landscape of Sierra Leone vividly, contrasting beauty with brutality. Some technical aspects do show their age—like certain digital effects that can feel artificial—but these don’t significantly dampen the overall experience. The soundtrack by James Newton Howard underscores the drama without veering into heavy-handed territory.

Blood Diamond scores high on several fronts. The performances by DiCaprio and Hounsou are standout elements, their evolving relationship carrying the film’s emotional heft. The pulse-pounding action sequences inject thrills while highlighting the chaos of civil war. Perhaps most importantly, the movie exposes the grim realities behind the glittering allure of diamonds, educating audiences about child soldiers, forced labor, and the complicity of international markets in perpetuating violence. Though it sometimes leans into melodrama and moralizing dialogue, the film’s commitment to its message is fairly unambiguous and impactful.

That said, the film sometimes succumbs to the trappings of big-budget Hollywood storytelling. The plot can feel overly convenient, with coincidences and resolutions that stretch credibility. Supporting characters, aside from the leads, are underdeveloped, mainly functioning as plot devices. Dialogue can at times be heavy-handed, particularly in the final act where scenes verge on preachy. Some narrative contrivances—like the recovery and passing of the pink diamond—can feel forced even in a tense, action-driven context. On the technical side, a few CGI moments fail to hold up under scrutiny, but these are minor irritants in an otherwise immersive film.

An important and unavoidable observation about Blood Diamond is how, like many of Edward Zwick’s previous action-dramas, it leans heavily into the “white savior” trope, if not outright embodying it. This trope centers a white protagonist—in this case, Danny Archer—who becomes the crucial figure in the salvation or redemption of non-white characters and communities. While the film sheds light on the horrors and complexity of Sierra Leone’s civil war and the conflict diamond trade, the narrative perspective and moral center overwhelmingly revolve around Archer’s personal journey from cynical mercenary to reluctant hero. The African characters, though vital and powerful especially through Hounsou’s Solomon, are often cast in more reactive roles, with Archer positioned as the key agent for change. The film also features a white journalist, Maddy Bowen, reinforcing this pattern.

Zwick’s leanings toward this trope are not new or isolated. His earlier films Glory (1989) and The Last Samurai (2003) also engage with the white savior narrative. Glory, a Civil War epic about the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, tells a historically significant story but largely centers on Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, a white officer played by Matthew Broderick, as the story’s main emotional and narrative anchor. The film has been noted for respectfully addressing racism and heroism but still revolves around Shaw’s perspective and sacrifice as a key redemptive figure for the African American soldiers. The Last Samurai similarly places Tom Cruise’s character, an American military advisor, at the heart of a narrative about Japanese samurai culture and resistance, blending cultural appreciation with the problematic trope of the white outsider who becomes indispensable to a non-white community’s fate.

This approach, familiar in Hollywood, walks the line between broad audience engagement and ethical storytelling. Zwick’s films often balance studio and audience expectations with a desire to tell compelling stories about marginalized communities. Yet inevitably, this framing simplifies complex histories and contributes to critiques that such films center whiteness and diminish the agency of non-white characters.

Casually speaking, Blood Diamond is not subtle, but that directness is part of its appeal. For viewers looking for a gripping action drama with strong performances and an ethical core, it delivers. It entertains while providing a sobering look at the high cost of luxury goods. DiCaprio’s portrayal of Danny Archer, complete with an authentically worked-on accent from the region, puts to rest doubts about his action lead capabilities. Hounsou’s performance lingers emotionally, especially in scenes grappling with the trauma of child soldiering. The violence depicted is raw and unvarnished, contributing to a visceral sense of the film’s urgent themes.

Running for about two hours and 23 minutes, the film has plenty of time to develop its complex story and deliver tense action sequences without feeling rushed or padded. Ultimately, Blood Diamond is an effective historical thriller that balances high stakes and moral urgency. While it’s not nuanced in every aspect and occasionally tips into cliché and convenience, it makes a strong case for itself beyond mere entertainment. Whether you’re interested in history, action, or the human stories behind the diamond trade, this film offers a thought-provoking, emotionally resonant experience. Leonardo DiCaprio’s dedication to portraying a Rhodesian mercenary authentically, especially through his accent work, is a highlight that complements the film’s broader narrative ambitions.