Cliff Spab (Stehpen Dorff), his friend Joe Dice (Jack Noseworthy), and teenager Wendy Pfister (Reese Witherspoon) are in the wrong convenience store at the wrong time and end up being taken hostage by a group of masked terrorists who have guns and video cameras. For 36 days straight, their ordeal is broadcast live on television. They become the number one show in the country and Cliff’s nihilistic attitude makes him a star. When the terrorists threaten to kill him, he spits back, “So fucking what!?” Alienated young people take up S.F.W. as a personal chant and credo. When Joe finally fights back, both he and the terrorists are killed in the shoot-out. Wendy and Cliff are now celebrities, even though they don’t want to be. Released into the real world, Cliff has to deal with everyone wanting to make money off of him. His alienation has been turned into a product. He just wants to be reunited with Wendy but his fans want him to tell them how to live their lives. Fandom turns out be a fickle beast.

Cliff Spab (Stehpen Dorff), his friend Joe Dice (Jack Noseworthy), and teenager Wendy Pfister (Reese Witherspoon) are in the wrong convenience store at the wrong time and end up being taken hostage by a group of masked terrorists who have guns and video cameras. For 36 days straight, their ordeal is broadcast live on television. They become the number one show in the country and Cliff’s nihilistic attitude makes him a star. When the terrorists threaten to kill him, he spits back, “So fucking what!?” Alienated young people take up S.F.W. as a personal chant and credo. When Joe finally fights back, both he and the terrorists are killed in the shoot-out. Wendy and Cliff are now celebrities, even though they don’t want to be. Released into the real world, Cliff has to deal with everyone wanting to make money off of him. His alienation has been turned into a product. He just wants to be reunited with Wendy but his fans want him to tell them how to live their lives. Fandom turns out be a fickle beast.

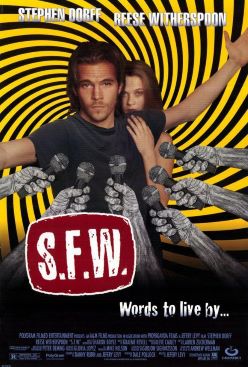

Earlier this morning, I came across a news item that Jefery Levy, the director of S.F.W., had died at the age of 67. S.F.W. used to show up frequently on cable in the 90s but I hadn’t thought about it in years. When I first saw S.F.W., I didn’t care much for it. Cliff came across as being a poseur and Stephen Dorff came across like he was way too impressed with himself. With John Roarke playing everyone from Phil Donahue to Sam Donaldson and Gary Coleman appearing as himself, the movie seemed like it was trying too hard to be outrageous. Looking back on it now, though, I realize S.F.W. may not have been a good movie but it was still a very prophetic movie. What seemed implausible in the 90s — like the 36-day live stream from inside the convenience store hostage situation and Cliff Spab’s fans switching their allegiance to a self-righteous virgin who yells that everything matters while trying to assassinate him — feels far too plausible today.

In 1994, S.F.W. and Jefery Levy predicted the 2020s. The only thing it got wrong was having Cliff Spab not wanting to be a famous. Today, Cliff Spab would probably be presenting the Best Podcast award at the Golden Globes.