“Someday we might look back on this and decide that Saving Private Ryan was the one decent thing we were able to pull out of this whole godawful, shitty mess.” — Sergeant Horvath

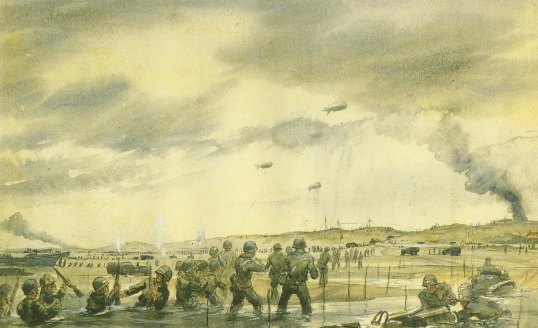

Saving Private Ryan stands as a landmark achievement in war cinema, intricately weaving immersive battle scenes, rich character dynamics, and profound moral themes into a nearly three-hour exploration of World War II’s human cost. One of its most remarkable features is the opening Omaha Beach landing sequence, a meticulously crafted, over 24-minute depiction of warfare’s brutal reality. Spielberg deploys a cinema verité style with handheld cameras capturing disorientation and chaos through the soldiers’ eyes. The sound design envelops the viewer in a sensory onslaught—gunfire, shouting, explosions—creating a visceral experience that immerses audiences directly in the terror and confusion of D-Day.

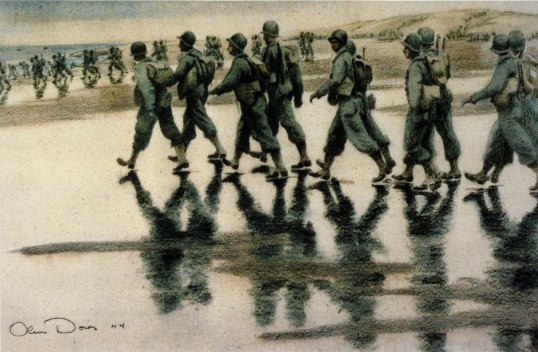

The filming process drew heavily on historical accuracy, with the production shot on the coast of County Wexford, Ireland, employing amputee actors and practical effects over computer graphics to simulate violent injuries and battlefield horrors. Muted tones evoke wartime photographs, and rapid, shaky editing conveys the disorganized, frantic environment soldiers endured. Consulting WWII veterans and historians, Spielberg created a sequence that reshaped cinematic portrayals of war, influencing how future films would approach the genre’s raw immediacy and emotional weight.

The film’s narrative follows a squad led by Captain Miller on a mission to locate and bring home Private James Ryan, whose three brothers have been killed in combat. The mission is steeped in the real-life tragedy of the five Sullivan brothers who died together aboard the USS Juneau in the Pacific, prompting military policies to prevent similar familial devastation. This historical context frames the story’s ethical heart: risking several men’s lives to save one, raising enduring questions about the value of individual sacrifice within the broader war.

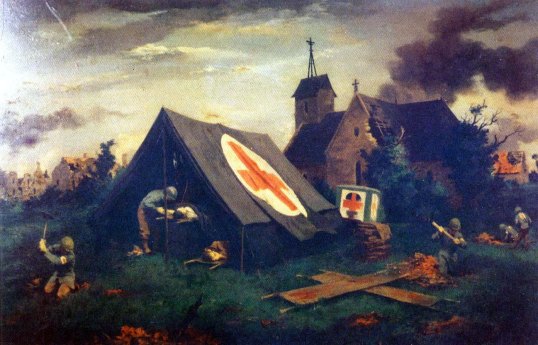

In Saving Private Ryan, sacrifice is portrayed ambiguously—not as the sacrifice of a single hero but as the collective cost borne by the men tasked with rescuing one individual under perilous conditions. As the squad journeys through the war-torn French countryside, the deaths, injuries, and tensions they face underscore war’s randomness and the difficulty of weighing one life against many. The narrative refuses to romanticize or simplify, instead confronting the audience with the tragic truth that countless soldiers lose their lives without recognition or purpose, while some survive against staggering odds.

Duty and camaraderie thread throughout the film, portrayed through the soldiers’ evolving relationships and personal struggles. Each grapples with loyalty not only to their mission but to their fellow men and their own moral codes.

Integral to the film’s power is Tom Hanks’s layered performance as Captain John Miller. Hanks breathes life and emotional depth into Miller, portraying him as a man shaped by civilian life—revealed poignantly when he discloses his pre-war profession as a schoolteacher—now transformed by the relentless demands of war. He embodies an officer who is both composed and vulnerable, carrying the heavy burden of leadership with quiet dignity. Hanks’s portrayal reveals the internal struggles beneath Miller’s stoic exterior: moments of doubt, moral conflict, and fatigue subtly expressed through a trembling hand or a weary gaze. This humanity makes Miller relatable, as a man trying to maintain order and purpose amid chaos.

Hanks skillfully balances Miller’s authoritative presence with warmth and empathy, particularly evident in his paternal interactions with younger soldiers, reinforcing Miller’s role as both a leader and protector. His nuanced acting delivers the complexity of a man constantly negotiating duty and compassion. In scenes of high tension or moral quandaries, Hanks conveys the weight of command while allowing glimpses into Miller’s psychological strain, deepening the film’s emotional resonance.

Following Hanks’s Miller, a standout amongst the supporting cast is Tom Sizemore’s portrayal of Technical Sergeant Mike Horvath, Miller’s steady second-in-command. Sizemore embodies the pragmatic, battle-hardened soldier whose loyalty and experience provide emotional grounding for the squad. Sizemore portrays Horvath’s weariness and quiet commitment, adding layers of realism that deepen the exploration of how war reshapes individuals. The chemistry and shared history between Miller and Horvath are palpable, illustrating the bonds that sustain soldiers through hardship and lending emotional weight to the narrative.

The film wrestles with intense moral ambiguity throughout. The mission’s premise—to risk many lives to save one—compels both characters and viewers to confront complex questions about justice, value, and the cost of war. Scenes presenting difficult choices, such as the decision to spare or execute prisoners, dramatize these ethical dilemmas and highlight the emotional burdens borne by soldiers.

Technically, the film excels, with Janusz Kaminski’s dynamic cinematography capturing both the chaos of battle and intimate moments with evocative clarity. The immersive sound design reinforces the brutal reality, stripping warfare of glamor and confronting audiences with its daunting human costs.

Despite the overwhelming destruction and loss, Saving Private Ryan offers moments of humanity and hope. The rescue mission serves as a fragile symbol of compassion in the midst of devastation, while the film’s closing reflections on memory and legacy emphasize the lasting significance of sacrifice and survival.

Saving Private Ryan stands as a monumental achievement in the war genre, combining visceral combat realism, compelling characters, and moral complexity. Through Hanks’s deeply human Captain Miller and the nuanced supporting performances, especially Sizemore’s grounded Horvath, the film explores themes of sacrifice, duty, and brotherhood with unflinching honesty. Its enduring legacy lies in its unvarnished yet empathetic portrayal of war’s cost and the profound sacrifices made by those who lived it.