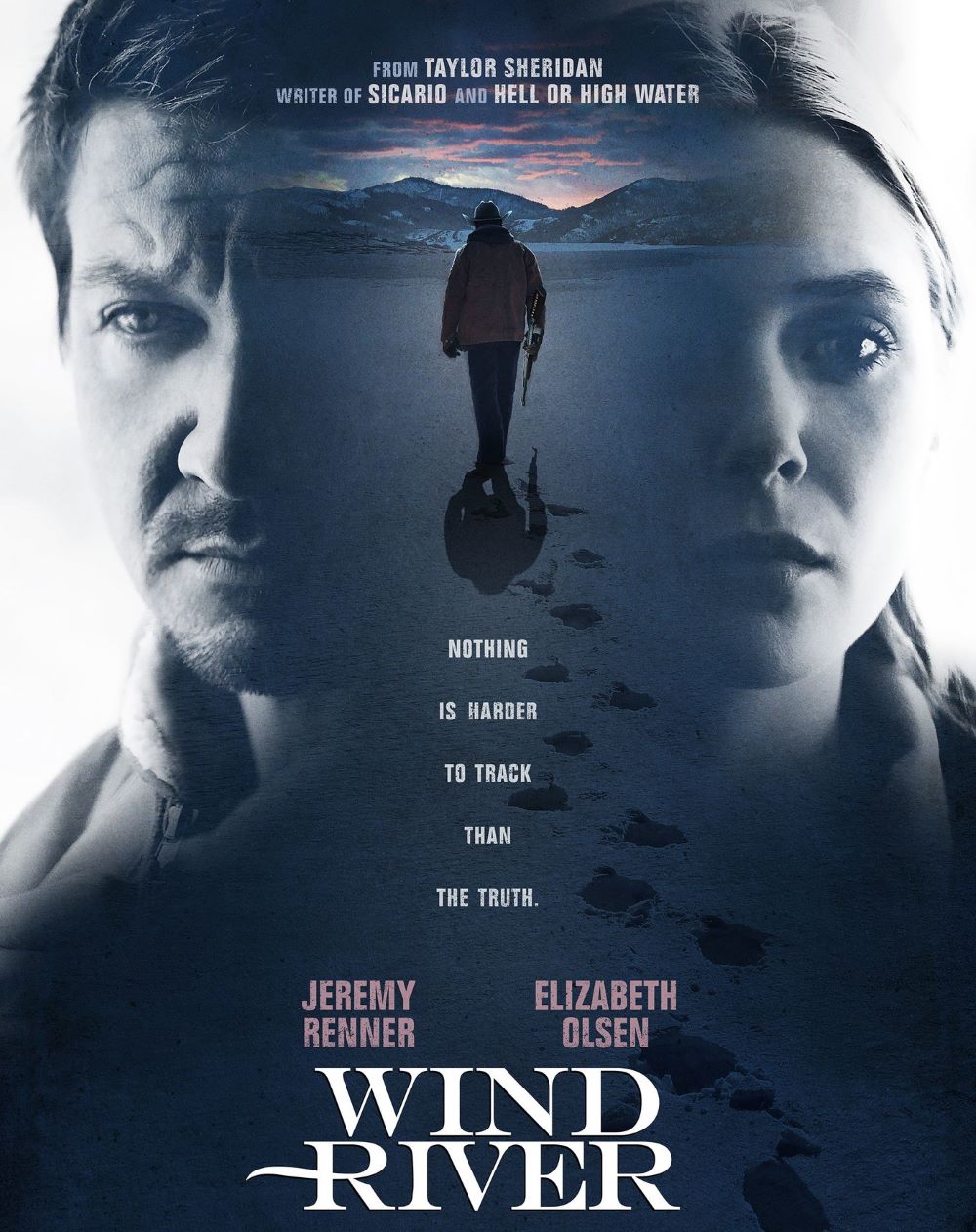

“Luck don’t live out here.” — Cory Lambert

Wind River is a gripping crime thriller set against the stark, frozen backdrop of Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation, where U.S. Fish and Wildlife tracker Cory Lambert teams up with rookie FBI agent Jane Banner to investigate the brutal death of a young Native American woman named Natalie Hanson. Wind River marks the third film in Taylor Sheridan’s American Frontier trilogy that he wrote—following Sicario and Hell or High Water—and it’s the first where Sheridan steps into the director’s chair himself, bringing his sharp eye for gritty realism to the helm. Clocking in at just under two hours, it delivers a mostly positive experience through strong performances, atmospheric visuals, and a script that builds suspense without unnecessary flash, though it occasionally leans on familiar tropes.

Right from the opening moments, Wind River immerses you in a world of isolation and harsh beauty. Snow-covered plains stretch endlessly under a pale sky, and the crunch of boots on ice sets an immediate tone of vulnerability. Cory, played with quiet intensity by Jeremy Renner, discovers Natalie’s frozen body while tracking a mountain lion that’s been preying on livestock. She’s barefoot, half-naked, and miles from any help—details that hit hard and underscore the film’s core mystery: what happened to her, and why does it feel like no one cares? Renner nails the role of a man haunted by his own past loss—his teenage daughter died under mysterious circumstances a few years back—making Cory a grounded everyman rather than a superheroic cowboy. His subtle grief adds layers to every scene, turning routine investigation beats into something personal and raw.

Enter Elizabeth Olsen as Jane Banner, the FBI agent flown in from Vegas who’s clearly out of her depth in sub-zero temperatures and jurisdictional limbo. Olsen brings a mix of determination and wide-eyed realism to the part, avoiding the cliché of the big-city hotshot who learns frontier wisdom overnight. She’s tough but human—hypothermic after a chase, throwing up from the cold, yet pushing through because Natalie deserves justice. The dynamic between Cory and Jane is one of the film’s highlights: no forced romance, just mutual respect born from necessity. Sheridan smartly lets their partnership evolve organically, with Cory’s local knowledge filling Jane’s gaps in protocol and reservation politics. It’s refreshing to see two leads click without sparks flying, focusing instead on shared purpose amid tragedy.

The script shines in its efficient storytelling. Sheridan wastes no time on exposition dumps; instead, he weaves backstory through quiet conversations and flashbacks that pack emotional punch. We learn about the epidemic of missing Indigenous women—thousands vanish yearly, often ignored by media and law enforcement—via stark statistics flashed on screen and through the eyes of Natalie’s family. Gil Birmingham delivers a heartbreaking performance as her father, Martin, a stoic oil rig worker whose rage simmers beneath a veneer of resignation. His scenes with Cory, especially a late-night talk by a bonfire, cut deep, exploring themes of fatherly failure and systemic neglect without preaching. Birmingham’s restrained power elevates what could have been a stock grieving parent into a standout supporting role.

Visually, Wind River is a stunner, thanks to cinematographer Ben Richardson. Those vast, snowy expanses aren’t just pretty—they mirror the characters’ emotional desolation and amplify the stakes. An early tracking sequence, with Cory following Natalie’s footprints in the snow, builds dread masterfully, the silence broken only by wind and labored breaths. The film shifts tones seamlessly: slow-burn investigation gives way to visceral action in the third act, including a raid on an oil site trailer that’s tense, realistic, and over in a flash—no prolonged shootouts or slow-mo heroics. Sound design plays a big role too; the howling wind and muffled gunshots make every moment feel immediate and unforgiving.

Sheridan’s direction keeps things taut without rushing the build-up. This is a slow-burner that earns its pace, letting tension simmer through everyday details like jurisdictional squabbles with underfunded tribal police or Cory teaching Jane to dress for the cold. Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’s score is another winner—sparse, haunting electronics that evoke loneliness rather than bombast. It underscores key scenes without overpowering them, much like the film itself avoids Hollywood excess.

That said, Wind River has its stumbles. Pacing dips in the middle, with some dialogue-heavy stretches that spell out themes a tad too explicitly—like chats about reservation poverty or ignored crimes. It can feel heavy-handed, pulling you out of the immersion. A few characters, like the bumbling FBI contingent or security guards, border on caricature, though the leads stay nuanced. The violence, while sparse and purposeful, includes a harrowing assault scene that’s tough to watch; it’s crucial to the story but might overwhelm sensitive viewers. And while the film tackles real issues facing Native communities, some critics note it centers white protagonists in a Native story, though Sheridan consulted tribal members and cast authentically.

Still, these are minor gripes in a film that largely succeeds on its own terms, especially as the capstone to Sheridan’s trilogy exploring America’s frayed edges. The ending delivers catharsis without easy answers, leaving you with a chill that lingers. Cory gets a measure of redemption, Jane gains hard-won insight, and the reservation’s harsh realities feel unflinchingly real. It’s the kind of movie that sticks because it respects your intelligence—connecting dots about corruption, indifference, and human cost without hand-holding.

What elevates Wind River above standard thrillers is its humanity. Every character, even antagonists, feels fleshed out rather than villainous stock. The oil workers aren’t cartoon evil; they’re desperate men making brutal choices in a forgotten corner of America. Sheridan, drawing from his own ranching background, captures blue-collar grit authentically—no glamour, just survival. Renner’s Cory hunts for a living, bottles his pain, and bonds with his ex-wife’s new family in tender asides that ground the procedural. Olsen’s Jane evolves from outsider to advocate, her arc subtle but satisfying.

The film’s relevance hasn’t faded since its 2017 release. With ongoing conversations around Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), it spotlights a crisis stats show claims over 5,000 cases annually, many unsolved due to jurisdictional messes. Wind River doesn’t solve it but demands attention, blending genre thrills with advocacy seamlessly.

In a crowded field of crime dramas, Wind River stands out for its chill factor, both literal and figurative. It’s not reinventing the wheel, but Sheridan proves he’s a triple threat: writer, director, voice for the voiceless. Renner and Olsen lead a tight ensemble, and the Wyoming wilderness becomes a character itself. If you dig thoughtful thrillers like Hell or High Water or Sicario, this one’s essential. It’s mostly positive vibes from me—intense, moving, and worth cranking up the thermostat for.

Sheridan’s ear for dialogue keeps things natural—terse exchanges crackle with subtext, like Cory’s line to Martin about enduring loss as a father that hits like a gut punch with simple words carrying profound weight. The film trusts silence too; long shots of characters staring into the void say more than monologues ever could, while technically it’s polished with editing that snaps during action and breathes during reflection. Even smaller roles shine—Kelsey Asbille as Natalie brings fire in limited screen time, and James Jordan plays an irredeemable private security contractor so well. Balanced against its preachiness, Wind River earns its emotional heft, dragging occasionally sure, but the payoff of an explosive finale and quiet closure makes it worthwhile, with power in inevitability and quiet fury as Sheridan avoids exploitative rape-revenge clichés to focus on aftermath and accountability.

Wind River delivers assured direction in Sheridan’s feature debut, memorable performances, and a compelling story that resonates. It refreshes the thriller genre with its blend of tension and substance.