Telly Savalas would have been 104 years old today. He’s been in many of my favorite movies so I’m glad to celebrate him today with 4 Shots from 4 of my favorites!

Telly Savalas would have been 104 years old today. He’s been in many of my favorite movies so I’m glad to celebrate him today with 4 Shots from 4 of my favorites!

“You want to shoot me, go ahead. It won’t matter. I’ve seen things you wouldn’t believe.” — The Stranger

The Western Wound: Horror, History, and the Haunting of Frontier Mythology

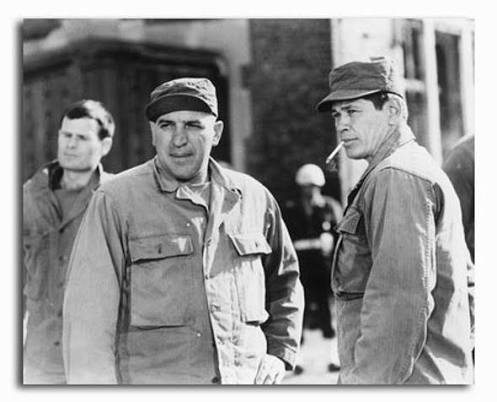

Horror profoundly shapes, distorts, and reframes the American Western, complicating familiar narratives of lawmen and outlaws with the uncanny specter of trauma, dread, and evil. Few films demonstrate this transformation more powerfully than Ravenous (1999), Bone Tomahawk (2015), and High Plains Drifter (1973). These three Westerns push beyond genre conventions, leveraging horror’s capacity to unsettle, destabilize, and haunt—creating experiences that are as philosophically provocative as they are viscerally unsettling. Rather than merely incorporating horror aesthetics into a Western setting, each film employs horror as a core thematic device to interrogate violence, community, morality, and the dark legacies of frontier expansion.

High Plains Drifter’s isolation in the arid Nevada desert is more than a physical setting; it externalizes the moral barrenness and guilt festering within the town of Lago. The oscillation between relentless sunlight and dense fog creates a hallucinatory space where natural laws are suspended, and supernatural retribution manifests. Central water imagery—the fog rolling off the lake, the lake itself—serves as a liminal zone, symbolizing the boundary between life and death, past and present, justice and vengeance. The Stranger’s spectral emergence from the desert heat haze hints at his otherworldly nature, turning the town’s landscape into a haunted battleground where redemption is elusive and suffering endemic.

Ravenous’s setting in the snowy Sierra Nevada mountains during the Mexican-American War imbues its horror with claustrophobic dread. Fort Spencer’s remoteness in the face of towering, hostile peaks and unrelenting winter transforms the natural environment into a gothic prison. This wilderness is both physical and psychological, oppressive in its vastness and merciless in its cold. The film uses this setting to amplify the existential terror wrought by cannibalism, suggesting an inescapable cycle of consumption where survival becomes monstrous. Deep shadows, filtered natural lighting, and long quiet scenes evoke dread as much as extreme violence.

In Bone Tomahawk, the stark, sunbaked deserts and towering rock formations of the American Southwest form an ominous landscape embodying ancient and unknowable horror. The frontier town is a fragile outpost at civilization’s edge, surrounded by a wild, menacing wilderness. The deep canyons serve as metaphorical gateways to past atrocities, echoing the silent histories of indigenous trauma and colonial violence. The oppressive silence and vastness underscore humanity’s diminutiveness and vulnerability, while the jagged terrain symbolizes the harshness of both nature and history’s brutal forces.

The Stranger in High Plains Drifter manifests the blurring boundaries between justice and vengeance, heroism and monstrosity. His actions—including an unsettling rape scene—force a confrontation with the darkest aspects of human nature, showing how violence corrupts even those who claim righteousness. His ghostly status and ruthless methodology suggest he is a representation of collective guilt made tangible, punishing the town’s sins with otherworldly finality. The film invites viewers to question whether vengeance restores balance or merely perpetuates horror.

In Ravenous, cannibalism literalizes the primal urge to consume not only flesh but identity and sanity, transforming survivors into monsters. The character Ives, charismatic and terrifying, embodies this transformation, seducing others into a vortical descent of brutality. The film’s psychological horror arises from the contagion of hunger and madness, the breakdown of social and moral order amid desolation. It probes existential questions about survival, morality, and the dissolution of self.

Bone Tomahawk depicts transformation through the confrontation with an ancient, savage tribe whose brutality transcends ordinary human evil. The characters’ exposure to this primordial terror strips away civilized facades, forcing characters and viewers to acknowledge the latent barbarity within humanity. The film’s horror is both external—in the violent acts of the tribe—and internal—in the psychological unravelling of the rescue party. This duality highlights the wilderness as both physical terrain and psychic landscape of primal fear.

The communal failure in High Plains Drifter reveals how collective cowardice and betrayal corrupt society. Lago’s townsfolk enable the marshal’s murder and face the Stranger’s supernatural justice as a consequence. Their moral bankruptcy transforms the town into a cursed locus of horror, symbolizing how collective sin corrupts the social fabric and invites ruin.

Ravenous portrays community breakdown within the remote outpost, where isolation breeds paranoia, selfishness, and violence. The collapse of trust and order mirrors the broader failure of frontier society to contain human baseness under extreme conditions, suggesting society itself is a fragile construct vulnerable to collapse.

In Bone Tomahawk, the fragile rescue party embodies the precariousness of social cohesion facing profound evil. Their doomed mission stresses how thin the veneer of civilization is, shattering under pressure from ancient horrors. The film critiques assumptions of order and control, emphasizing the ease with which human society can crumble.

Violence in High Plains Drifter is unending, spectral, and morally ambiguous. The Stranger’s vengeance refuses neat closure, illustrating cycles of violence that leave deeper scars rather than justice. The film redefines violent retribution as torment, destabilizing conventional heroic narratives.

Ravenous entwines violence with survival horror and existential dread. The ritualistic cannibalism is a metaphor for moral and spiritual corrosion, forcing characters and audiences to face the horrors wrought by the primal fight for survival at civilization’s edge.

Bone Tomahawk presents violence as slow, ritualistic, and ancient—an elemental force indifferent to human ethics. Its stark, realistic depiction immerses viewers in fear and helplessness, rejecting conventional catharsis and highlighting the terror of primal brutality.

High Plains Drifter blends ghostly and surreal imagery to explore unresolved sin and cultural guilt. The Stranger is both avenger and specter of collective trauma, with symbolic elements—such as the red-painted town and unmarked graves—that deepen the meditation on punishment and desolation.

Ravenous uses cannibalism and wilderness as symbols of consumption and destruction intrinsic to frontier expansion. Horror here reflects existential struggles with survival, cultural annihilation, and moral ambiguity, set against an environment of engulfing nature and history.

Bone Tomahawk evokes frontier horror as a metaphor for repressed histories and cultural erasure. The savage tribe symbolizes ancestral trauma, while the desolate landscapes underscore the lingering presence of buried horrors that haunt the Western imagination.

Ravenous, Bone Tomahawk, and High Plains Drifter deepen the Western genre’s reckoning with violence, morality, and civilization’s fragility. Ravenous allegorizes hunger and expansion’s destructive appetite through cannibalism, revealing survival’s costs to identity and culture. Bone Tomahawk exposes historical violence and trauma encoded in landscape and myth, demonstrating Western justice’s limits. High Plains Drifter dramatizes unresolved guilt and vengeance through spectral retribution, challenging sanitized Western heroism.

The films’ central horrors—the Stranger’s merciless vengeance, the cannibal’s transformative hunger, and the doomed rescue mission into darkness—serve as meditations on violence, communal complicity, and the absence of redemption. They unmask the American West and America itself as terrains haunted by deep, unresolved sins and moral ambiguity. In marrying supernatural and psychological horror, these films offer a complex, layered critique of frontier myth, turning the Western from a tale of conquest into a haunted narrative of trauma, survival, and moral reckoning.

High Plains Drifter uniquely embodies ambiguity between supernatural revenge and psychological torment. The Stranger’s ghostlike qualities and resurrection to avenge his murder firmly anchor a supernatural interpretation. His eerie manifestations—such as the bullwhip’s sound triggering vivid nightmares and his mysterious appearance from the desert heat—signal a spectral force beyond human comprehension. Yet, on a psychological level, the Stranger can be viewed as the materialization of the town’s collective guilt and suppressed trauma. This duality enriches the narrative, allowing viewers to interpret the horror as either literal supernatural vengeance or a psycho-spiritual reckoning of internal moral collapse.

Ravenous blurs supernatural and psychological horror by mixing the tangible terror of cannibalism with metaphysical dread. The figure of Ives carries almost mythic qualities—his charismatic yet monstrous presence suggests an otherworldly evil, a contagion consuming the souls of men. The mountain wilderness functions as a liminal space transcending reality, where madness and primal urges surface. This ambiguity invites readings of the horror as both external supernatural curse and internal psychological disintegration, reflecting survival’s dehumanizing cost amidst isolation and guilt.

Bone Tomahawk grounds itself mostly in realistic terror but invokes mythic supernatural threads through the savage tribe’s almost fantastical menace. Their brutal, ritualized violence carries residues of ancestral curses and primal fears that exceed mere human malevolence. The film explores psychological horror through the characters’ terror and helplessness confronting an unknowable evil, making the wilderness and tribe a metaphor for the abyss of human and historical trauma. Thus, horror emerges as both a tangible threat and a psychological abyss threatening identity and sanity.

This interplay of supernatural and psychological horror amplifies these films’ thematic depth. By refusing to confine horror to one domain, they portray the Western frontier as a space haunted simultaneously by ghosts—whether spiritual, historical, or personal—and inner demons manifesting as guilt, fear, and madness.

Ultimately, horror in these Westerns is not merely a matter of frightening events but a profound engagement with unsettled histories and psyches. This dynamic makes their terror resonate long after the screen fades to black, marking the Western as a genre haunted not only by outlaws and the wilderness but by the specters within us all.

Horror profoundly alters the Western genre’s narrative, revealing it as a cultural wound, a landscape haunted by the ghosts of its own violent history and moral contradictions. By challenging sanitized myths and exposing the fragility beneath civilization’s veneer, Ravenous, Bone Tomahawk, and High Plains Drifter not only frighten but provoke deep reflection on the legacies of violence and the nature of justice itself—capturing the horror at the heart of the American story.

“Don’t count on me to make you feel safe.” — The Stranger

High Plains Drifter stands as one of the bleakest, most enigmatic entries in Clint Eastwood’s filmography—a Western that bleeds unmistakably into the realms of psychological and supernatural horror. This 1973 film is not just another dusty tale of lone gunfighters and frontier justice. It’s a nightmare set in broad daylight, a morality play whose hero is more monster than man.

Eastwood’s Stranger comes riding into the town of Lago from the shimmering desert, a silhouette both akin to and apart from his famed Man With No Name persona. The townsfolk are desperate, haunted by fear—less afraid of imminent violence, more of the sins they’ve half-buried. This is a place where a lawman was brutally murdered by outlaws while the townspeople looked away, their silence paid for with cowardice and greed. When the Stranger assumes command, he does so with often-gleeful sadism—kicking people out of their hotel rooms, replacing the mayor and sheriff with the dwarf Mordecai, and ordering that the entire town be painted red before putting “Hell” on its welcome sign.

There’s a surface plot: the Stranger is hired to protect Lago from the same three outlaws who once butchered its marshal. But he’s there for far more than that. The story unspools through dreamlike sequences, flashbacks that suggest the Stranger may well be an avenging spirit or a revenant—the dead lawman, spectral and merciless, returned to claim what the townsfolk owe to Hell itself.

The horror here isn’t about jump scares or gothic haunted houses. The supernatural lurks everywhere and yet nowhere. The Stranger moves with the implacable calm—and violence—of a slasher villain, transforming Lago into his personal stage for retribution. His nightmares, full of images of past atrocities, are painted with the same vivid brutality as the daytime violence. Eastwood’s use of silence, the squint of a face, the twitch of a pistol replaces musical cues in amplifying dread. The sound design evokes otherness—a howling wind, footsteps echoing across empty streets—that builds a shadow of terror around the Stranger’s presence.

This violence is hurried and brutal; its sexual politics unflinching. When the Stranger enacts revenge, he punishes not just the outlaws, but the townsfolk complicit in their crimes. There is little comfort in his sense of justice—the pleasures he takes border on sadistic. The film’s moral ambiguity cuts deeper than most Westerns or horrors: this is not a clear-cut tale of good versus evil, but a brutal reckoning of collective guilt, cowardice, and corruption.

Lago itself acts almost like a town stuck in purgatory—a holding pen between redemption and eternal damnation. The infamous “Welcome to Hell” sign the Stranger paints at the town’s entrance serves as a grim message. It’s no welcome to law and order, but a symbolic beacon to the very outlaws the Stranger is hired to confront, suggesting that Lago is a place where sin festers and punishes itself. The town’s dance with Hell is both literal and metaphorical. The inhabitants aren’t just awaiting judgment; they have invited it in their desperate attempts to hide their cowardice and greed under the guise of civilization.

This notion of Lago as purgatory stands in sharp contrast to other recent horror Westerns, which serve as prime examples of the genre’s thematic spectrum. These films tend to focus on the primal terror of nature barely held at bay by the fragile veneer of civilization the settlers claim. They pit human beings against the ancient, untamed forces of the wilderness—whether monstrous creatures or surreal phenomena—emphasizing that the supposed order and progress of the West remain fragile and constantly threatened. This dynamic symbolizes the uneasy balance between civilization’s reach and nature’s primal power, often revealing how thin and tenuous that barrier truly is.

Among these, Bone Tomahawk and Ravenous stand out as vivid examples. Bone Tomahawk confronts menacing cannibals lurking in the wild, reminding viewers that the West’s order is fragile and under perpetual threat from untamed wilderness. Ravenous uses cannibalism and survival horror as metaphors for nature’s savage predation hidden beneath the polite façade of civilization—nature’s horrors masked but not erased.

By contrast, High Plains Drifter directs its horror inward, exposing the corruption that manifest destiny imposed on settlers themselves. Instead of fearing nature as an external force, the film presents settlers as haunted by their own moral failures and complicity in violence and betrayal. The Stranger’s vengeance is a reckoning with the darkness festering inside the community, a brutal meditation on guilt, collective cowardice, and the price of greed disguised as progress.

Eastwood’s film strips away the mythic promises of the American West as a land of freedom and opportunity, revealing instead the brutal reality of communities locked in complicity, violence masquerading as justice, and the moral rot at the heart of manifest destiny. This moral ambiguity and psychological depth give High Plains Drifter a unique position in the horror Western subgenre, elevating it beyond simple scares to a profound exploration of American cultural myths.

The Stranger is not a traditional hero but a spectral judge, embodying divine or supernatural retribution. His calm yet ruthless punishment exposes the cruelty, cowardice, and malevolence within Lago’s population, meting out a justice that is neither neat nor forgiving. His supernatural aura and sadistic tendencies make him an unforgettable figure of terror and fate.

Visually, the film’s harsh daylight contrasts with the romanticized Western landscapes of earlier films. Instead of shadows hiding evil, blinding light exposes the town’s moral decay. Characters are reduced to symbols of greed, fear, and cruelty, highlighting that the true horror lies within human nature and the failure to uphold justice.

High Plains Drifter operates on multiple levels—a Western, a ghost story, a horror film, and a dark morality play. It is a relentless meditation on justice and punishment and a dismantling of the traditional Western hero myth. Through layered narrative, stark visuals, and Eastwood’s chilling performance, it remains an essential entry in the horror Western canon.

For those seeking a Western that doesn’t just entertain but unsettles and challenges, High Plains Drifter offers an unforgiving descent into darkness. It strips away the comforting myths of the frontier and exposes the raw, rotting core beneath. Unlike other modern horror Westerns such as Bone Tomahawk and Ravenous, which confront external terrors lurking in the wilderness, this film turns its gaze inward—on the moral decay, guilt, and violence festering within the settlers themselves. It’s a brutal, haunting reckoning, and Eastwood’s Stranger is the cold, relentless agent of that reckoning. This is a journey into a hell both literal and psychological, where justice is merciless and safety is a long-forgotten promise.

“That is known a trouble with the curve.”

He’s a jerk but I still feel bad for Bo Gentry in this scene. He’s never going to make it in the majors if he can’t hit every type of pitch.

Just when I thought I was through with Clint Eastwood, they pull me back in!

Just when I thought I was through with Clint Eastwood, they pull me back in!

Actually, Clint Eastwood may have directed Invictus but that’s not why I’m writing about it today. I’m writing about it because today is Morgan Freeman’s 88th birthday. Everyone knows Morgan Freeman, of course, He’s the man with the amazing voice. If you ever want to hear someone narrate your life, you want that narrator to Morgan Freeman. Freeman is also one of our greatest actors and, for my money, Invictus is his best and more important performance.

Morgan Freeman plays the role of Nelson Mandela in Invictus. Taking place in 1994 and 1995, Invictus centers around the early days of the former political prisoner’s presidency of South Africa and how he used the 1995 Rugy World Cup to bring the tension-filled country together. While Afrikaner Francois Pinneaur (Matt Damon) unexpectedly leads South Africa to the finals of the World Cup, Mandela tries to guide South Africa into the post-Apartheid era.

Playing a role like Nelson Mandela would have to intimidate even the most confident of actors but Freeman gives a warm, humorous, and believable performance of a man who became a living icon. Freeman captures both Mandela’s humanity and his canny political instincts and he never allow the performance to become a caricature. Freeman projects the wisdom that comes from a lifetime of refusing to be broken or defeated, despite the best efforts of both the Apartheid regime and the activists who think that, as president, Mandela is too much of a moderate and too quick to forgive. Freeman (and Matt Damon) give performances that help the film get over a few spots where it falls into the typical clichés of the sports genre. Invictus is a good tribute to both Mandela and the way competition can bring people together.

One final note: Invictus was filmed on location in South Africa. When Matt Damon’s character is shown the cell were Mandela spent 27 years of his life, Eastwood shows us the actual cell and it’s a reminder of the strength of Mandela that he not only survived but that he went on to lead his country.

I get the honor of closing out today’s Clint Eastwood birthday celebration so I’m going to share my favorite picture of Mr. Eastwood. This is from a 2014 issue of Esquire and it features a great American with a symbol of the great American pastime.

Happy birthday, Clint Eastwood!

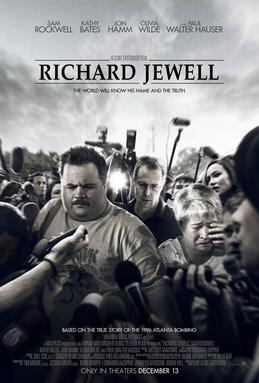

In 1996, a security guard named Richard Jewell should have been proclaimed a hero. He spotted an abandoned backpack in Centennial Park during the Atlanta Summer Olympics. Thinking that it could be a bomb, Jewell, insisting the proper security protocols be followed even though there was a concert going on, moved as many people as he could away from the backpack before it exploded. Two people died as a result of the explosion and 111 were injured. The number would have been much more catastrophic if not for Jewell’s actions.

In 1996, a security guard named Richard Jewell should have been proclaimed a hero. He spotted an abandoned backpack in Centennial Park during the Atlanta Summer Olympics. Thinking that it could be a bomb, Jewell, insisting the proper security protocols be followed even though there was a concert going on, moved as many people as he could away from the backpack before it exploded. Two people died as a result of the explosion and 111 were injured. The number would have been much more catastrophic if not for Jewell’s actions.

Jewell saved lives but he soon found himself the number one suspect. Overweight, a little bit nerdy, Southern accented and possessing a spotty work history, Richard Jewell did not fit the popular conception of a hero. After the FBI leaked that Jewell was their number one suspect, the press literally reported as if Jewell’s arrest was imminent. I’m old enough to remember the way that, for a month, the nightly news seemed like the counting the days until Jewell was charged. Jewell, however, was never arrested and eventually, he sued several media outlets for libel. After anti-abortion fanatic Eric Rudolph emerged as the number one suspect in the bombing, the three FBI agents who attempted to railroad Jewell were disciplined. One was suspended for five days without pay, which seems a light punishment for ruining a man’s life.

Clint Eastwood’s Richard Jewell was about the persecution of the title character, with Paul Walter Hauser playing Jewell, Kathy Bates playing his mother, Jon Hamm playing the arrogant FBI agent, Olivia Wilde playing the unethical journalist who first reported that Jewell was a suspect, and Sam Rockwell playing Jewell’s attorney. When Richard Jewell was released in 2019, there was a lot of debate about the way it presented both the media and the FBI. This was during the first Trump presidency and many critics felt that it was not the right time for a film about an irresponsible reporter and a corrupt FBI agent. But Eastwood’s film isn’t about the reporter or the FBI. Instead, like many of his films, it’s about a loner who does the right thing, refuses to compromise, and suffers for it. If the FBI and the media didn’t want to be presented as being villains in a movie about Richard Jewell, they should have thought twice before announcing to the the world that they thought he was a murderer.

Because of the controversy, Richard Jewell is one of Eastwood’s unfairly overlooked films. Along with directing in his usual straightforward manner, Eastwood gets a great performance out of Paul Walter Hauser and reminds us that not every hero looks like the Man With No Name. Even more importantly, Eastwood pays tribute to a man who deserved better than he was given by the world. Richard Jewell died 12 years before the film that was named after him was released. A lot of people wanted to sweep what happened to Richard Jewell under the rug. Eastwood, in one of the best of his later films, refused to let that happen.

I love baseball and all of its traditions.

I love the idea that a pitcher has a mental connection with his catcher. I love the stories of the minor leaguers who get their chance in the majors and who stun the world by coming out of nowhere to hit a home run on their first at bat. I love all the stories about which batters corked their bats and which pitchers could still manage to get away with throwing a spitball. I love baseball because watching it is a relaxing way to spend an afternoon but at the same time, the game is unpredictable. Just one hit can change the momentum of an entire game and, until that final out, the game could be won by anyone. I especially have a place in my heart for the legendary baseball scouts, the grouchy old men who would drive out to the middle of nowhere to watch a game and search for the next great homerun hitter.

That’s one reason why I hated Moneyball. I thought Brad Pitt, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Chris Pratt, and Jonah Hill all did a good job and I loved Brent Jennings’s performance as Ron Washington but I hated the idea that the scouts and their instincts weren’t necessary because everything could just be determined by sabermetrics. The idea that an algorithm could tell you everything you needed to know about how to put a team together felt like a crime against everything that makes baseball special and it deeply offended me as a fan. Moneyball may feature a baseball team but it’s a movie about business, not the game.

That’s why I’m thankful for Trouble With The Curve.

Clint Eastwood stars as Gus Lobel, one of those plain-spoken, no-BS scouts that I love so much. All of the team owners might be into sabermetrics but Gus knows that the best way to scout a player is to actually hit the road and see him play. For Gus, scouting is all about instincts and his own gut feeling. Gus is everything that I love about baseball. He’s knows the game, he knows the players, and he doesn’t need an algorithm to tell him whether or not someone should be on the field.

The movie is about Gus scouting a player who has trouble hitting the curve. That’s something that Gus notices but the algorithm overlooks. Accompanying Gus is his daughter, Mickey (Amy Adams), who is proud to have grown up surrounded by plain-spoken, unpretentious baseball scouts like her father and who doesn’t understand why Gus never took her on the road when she was younger. Mickey falls for a younger scout named Johnny (Justin Timberlake), their love based on their shared knowledge of baseball. I liked Mickey and Johnny as a couple and I appreciated the scenes where Mickey and Gus worked on their strained relationship but the best thing about this movie is that Gus gets to prove that he knows more about baseball than all the young whipper-snappers who think they understand the game.

Trouble With The Curve is a tribute to everything that baseball is truly about. It’s a movie that loves the game as much as I do. Clint Eastwood and Amy Adams are a perfect father/daughter duo. Who needs an algorithm when you’ve got Clint and Amy?

The Bridges of Madison County starts with a mystery. A sister and her brother try to find out why their mother requested that she be cremated and her ashes scattered from a bridge rather than be buried next to her late husband. Going through their mother’s things, they learn about four-day affair that she had with a photographer who was just passing through town and taking pictures of covered bridges.

Meryl Streep plays their mother, an Italian war bride named Francesca. Clint Eastwood plays the photographer, Robert Kincaid. The movie shows how Francesca, trapped in a loveless marriage, rediscovered her passion for life and love during her four-day affair with Robert. Robert rediscovered his love for photography. (I like to take pictures so I was happy for him.) With her family due home after a trip to the Iowa State Fair, Francesca had to decide whether to abandon them to pursue her affair with Robert. Since this is the first that her children have ever heard about the affair, it’s easy to guess what she decided to do.

My aunt loved this film and I like it too. It’s the most tasteful film about a woman being tempted to abandon her family that I’ve ever seen. It’s a film about adultery that the entire family can enjoy! The film looks beautiful and Meryl and Clint … wow! Let’s just say that they seemed to be really into each other. The two leads give such heartfelt performances that every moment felt authentic and by the end of the movie, I very much wanted to see Francesca’s ashes dumped over the side of that bridge. Whenever anyone says that Clint Eastwood could only play cops and cowboys, tell them to watch Bridges of Madison County.

In 1984’s City Heat, Clint Eastwood plays Lt. Speer, a tough and taciturn policeman who carries a big gun, throws a mean punch, and only speaks when he absolutely has to.

Burt Reynolds plays Mike Murphy, a private investigator who has a mustache, a wealthy girlfriend (Madeleine Kahn), and a habit of turning everything into a joke.

Together, they solve crimes!

I’m not being sarcastic here. The two of them actually do team up to solve a crime, despite having a not quite friendly relationship. (Speer has never forgiven Murphy for quitting the force and Murphy has never forgiven Speer for being better at everything than Murphy is.) That said, I would be hard-pressed to give you the exact details of the crime. City Heat has a plot that can be difficult to follow, not because it’s complicated but because the film itself is so poorly paced and edited that the viewer’s mind tends to wander. The main impression that I came away with is that Speer and Murphy like to beat people up. In theory, there’s nothing wrong with that. Eastwood is legendary tough guy. Most people who watch an Eastwood film do so because they’re looking forward to him putting the bad guys in their place, whether it’s with a gun, his fists, or a devastating one-liner. Reynolds also played a lot of tough characters, though they tended to be more verbose than Eastwood’s.

That said, the violence in City Heat really does get repetitive. There’s only so many times you can watch Clint punching Burt while various extras get gunned down in the background before it starts to feel a little bit boring. The fact that the film tries to sell itself as a comedy while gleefully mowing down the majority of the supporting cast doesn’t help. Eastwood snarls like a pro and Reynolds flashes his devil-may-care smile but, meanwhile, Richard Roundtree is getting tossed out a window, Irene Cara is getting hit by a car, and both Kahn and Jane Alexander are being taken hostage. Tonally, the film is all over the place. Director Richard Benjamin was a last-minute replacement for Blake Edwards and he directs without any sort of clear vision of just what exactly this film is supposed to be.

On the plus side, City Heat takes place in Kansas City in 1933 and the production design and the majority of the costumes are gorgeous. (Unfortunately, the film itself is often so underlit that you may have to strain your eyes to really appreciate it.) And the film also features two fine character actors, Rip Torn and Tony Lo Bianco, are the main villains. For that matter, Robert Davi shows up as a low-level gangster and he brings an actual sense of menace to his character. There are some good things about City Heat but overall, the film is just too messy and the script is a bit too glib for its own good.

Burt Reynolds and Clint Eastwood had apparently been friends since the early days of their careers. This was the only film that they made together. Interestingly enough, Reynolds gets the majority of the screentime. Eastwood may be top-billed but his role really is a supporting one. Unfortunately, Reynolds seems to be kind of bored with the whole thing. As for Clint, he snarls with the best of them but the film really doesn’t give him much to do.

A disappointing film, City Heat. Watching a film like this, it’s easy to see why Eastwood ended up directing himself in the majority of his films.