“Don’t count on me to make you feel safe.” — The Stranger

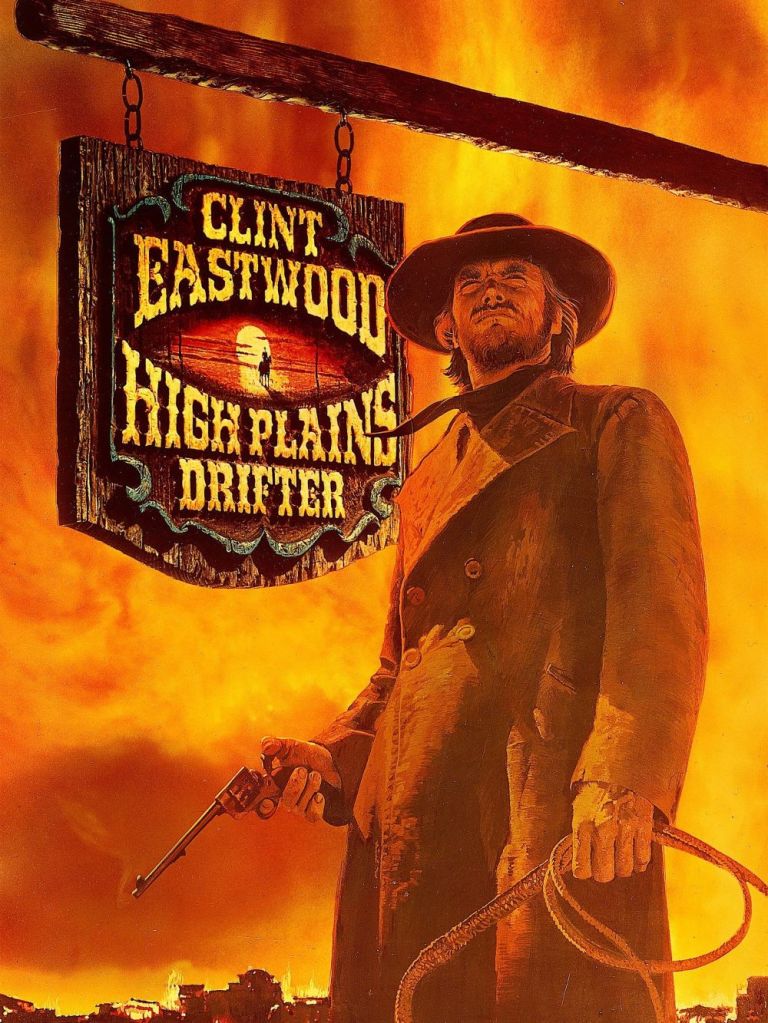

High Plains Drifter stands as one of the bleakest, most enigmatic entries in Clint Eastwood’s filmography—a Western that bleeds unmistakably into the realms of psychological and supernatural horror. This 1973 film is not just another dusty tale of lone gunfighters and frontier justice. It’s a nightmare set in broad daylight, a morality play whose hero is more monster than man.

Eastwood’s Stranger comes riding into the town of Lago from the shimmering desert, a silhouette both akin to and apart from his famed Man With No Name persona. The townsfolk are desperate, haunted by fear—less afraid of imminent violence, more of the sins they’ve half-buried. This is a place where a lawman was brutally murdered by outlaws while the townspeople looked away, their silence paid for with cowardice and greed. When the Stranger assumes command, he does so with often-gleeful sadism—kicking people out of their hotel rooms, replacing the mayor and sheriff with the dwarf Mordecai, and ordering that the entire town be painted red before putting “Hell” on its welcome sign.

There’s a surface plot: the Stranger is hired to protect Lago from the same three outlaws who once butchered its marshal. But he’s there for far more than that. The story unspools through dreamlike sequences, flashbacks that suggest the Stranger may well be an avenging spirit or a revenant—the dead lawman, spectral and merciless, returned to claim what the townsfolk owe to Hell itself.

The horror here isn’t about jump scares or gothic haunted houses. The supernatural lurks everywhere and yet nowhere. The Stranger moves with the implacable calm—and violence—of a slasher villain, transforming Lago into his personal stage for retribution. His nightmares, full of images of past atrocities, are painted with the same vivid brutality as the daytime violence. Eastwood’s use of silence, the squint of a face, the twitch of a pistol replaces musical cues in amplifying dread. The sound design evokes otherness—a howling wind, footsteps echoing across empty streets—that builds a shadow of terror around the Stranger’s presence.

This violence is hurried and brutal; its sexual politics unflinching. When the Stranger enacts revenge, he punishes not just the outlaws, but the townsfolk complicit in their crimes. There is little comfort in his sense of justice—the pleasures he takes border on sadistic. The film’s moral ambiguity cuts deeper than most Westerns or horrors: this is not a clear-cut tale of good versus evil, but a brutal reckoning of collective guilt, cowardice, and corruption.

Lago itself acts almost like a town stuck in purgatory—a holding pen between redemption and eternal damnation. The infamous “Welcome to Hell” sign the Stranger paints at the town’s entrance serves as a grim message. It’s no welcome to law and order, but a symbolic beacon to the very outlaws the Stranger is hired to confront, suggesting that Lago is a place where sin festers and punishes itself. The town’s dance with Hell is both literal and metaphorical. The inhabitants aren’t just awaiting judgment; they have invited it in their desperate attempts to hide their cowardice and greed under the guise of civilization.

This notion of Lago as purgatory stands in sharp contrast to other recent horror Westerns, which serve as prime examples of the genre’s thematic spectrum. These films tend to focus on the primal terror of nature barely held at bay by the fragile veneer of civilization the settlers claim. They pit human beings against the ancient, untamed forces of the wilderness—whether monstrous creatures or surreal phenomena—emphasizing that the supposed order and progress of the West remain fragile and constantly threatened. This dynamic symbolizes the uneasy balance between civilization’s reach and nature’s primal power, often revealing how thin and tenuous that barrier truly is.

Among these, Bone Tomahawk and Ravenous stand out as vivid examples. Bone Tomahawk confronts menacing cannibals lurking in the wild, reminding viewers that the West’s order is fragile and under perpetual threat from untamed wilderness. Ravenous uses cannibalism and survival horror as metaphors for nature’s savage predation hidden beneath the polite façade of civilization—nature’s horrors masked but not erased.

By contrast, High Plains Drifter directs its horror inward, exposing the corruption that manifest destiny imposed on settlers themselves. Instead of fearing nature as an external force, the film presents settlers as haunted by their own moral failures and complicity in violence and betrayal. The Stranger’s vengeance is a reckoning with the darkness festering inside the community, a brutal meditation on guilt, collective cowardice, and the price of greed disguised as progress.

Eastwood’s film strips away the mythic promises of the American West as a land of freedom and opportunity, revealing instead the brutal reality of communities locked in complicity, violence masquerading as justice, and the moral rot at the heart of manifest destiny. This moral ambiguity and psychological depth give High Plains Drifter a unique position in the horror Western subgenre, elevating it beyond simple scares to a profound exploration of American cultural myths.

The Stranger is not a traditional hero but a spectral judge, embodying divine or supernatural retribution. His calm yet ruthless punishment exposes the cruelty, cowardice, and malevolence within Lago’s population, meting out a justice that is neither neat nor forgiving. His supernatural aura and sadistic tendencies make him an unforgettable figure of terror and fate.

Visually, the film’s harsh daylight contrasts with the romanticized Western landscapes of earlier films. Instead of shadows hiding evil, blinding light exposes the town’s moral decay. Characters are reduced to symbols of greed, fear, and cruelty, highlighting that the true horror lies within human nature and the failure to uphold justice.

High Plains Drifter operates on multiple levels—a Western, a ghost story, a horror film, and a dark morality play. It is a relentless meditation on justice and punishment and a dismantling of the traditional Western hero myth. Through layered narrative, stark visuals, and Eastwood’s chilling performance, it remains an essential entry in the horror Western canon.

For those seeking a Western that doesn’t just entertain but unsettles and challenges, High Plains Drifter offers an unforgiving descent into darkness. It strips away the comforting myths of the frontier and exposes the raw, rotting core beneath. Unlike other modern horror Westerns such as Bone Tomahawk and Ravenous, which confront external terrors lurking in the wilderness, this film turns its gaze inward—on the moral decay, guilt, and violence festering within the settlers themselves. It’s a brutal, haunting reckoning, and Eastwood’s Stranger is the cold, relentless agent of that reckoning. This is a journey into a hell both literal and psychological, where justice is merciless and safety is a long-forgotten promise.