“Duty calls us to give more than our lives; it calls us to give our very souls.” — Capt. Juuzo Okita

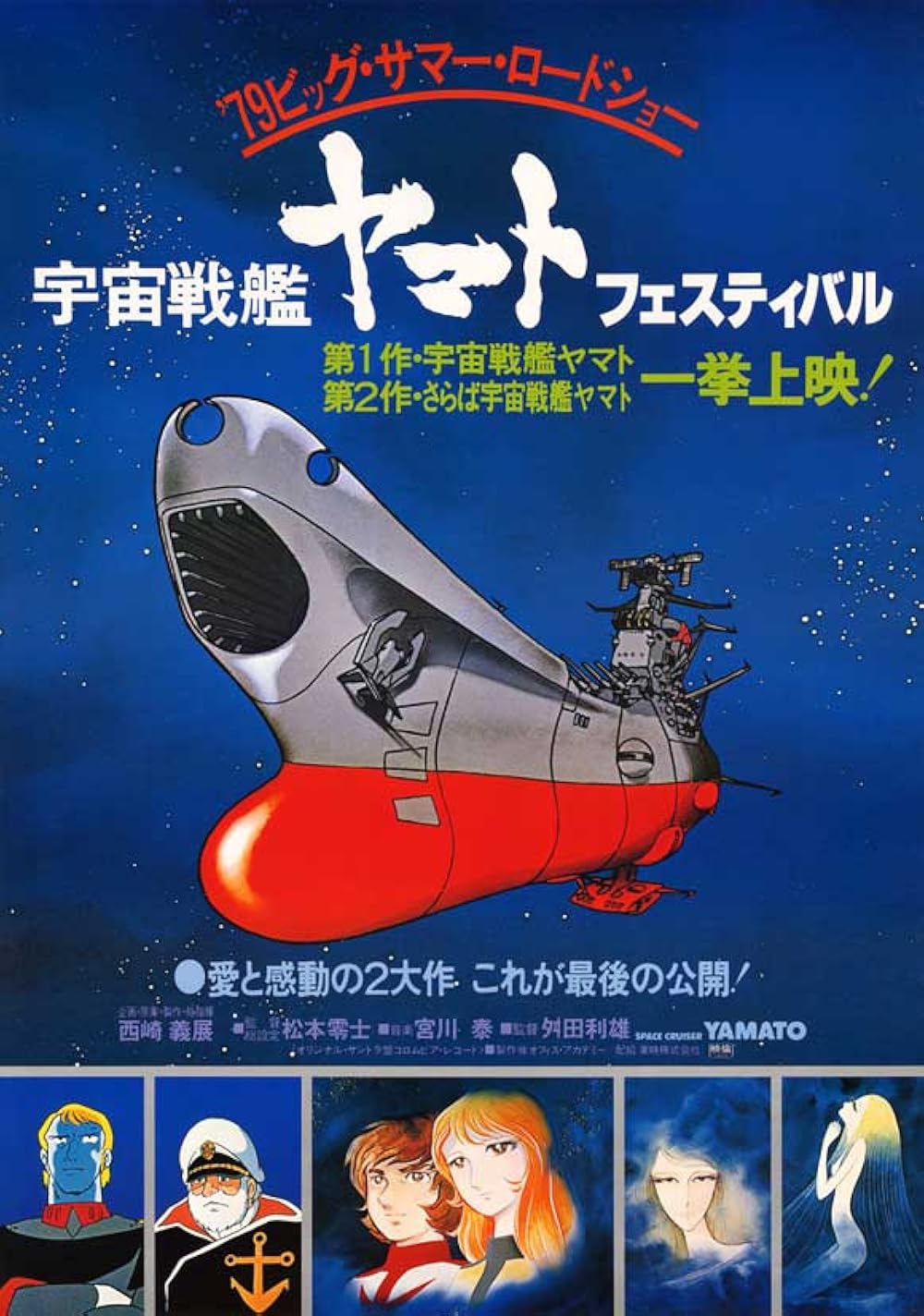

Space Battleship Yamato, which aired from 1974 to 1975, is a monumental anime series that shaped the medium’s evolution and continues to resonate deeply with audiences today. Directed by Leiji Matsumoto and produced by Yoshinobu Nishizaki, this 26-episode space opera follows the crew of the Yamato—a resurrected World War II battleship transformed into a spacefaring vessel—on a desperate mission to save an irradiated Earth.

Set in the late 22nd century, Earth has been devastated by radiation from relentless attacks by the alien Gamilas. The surface is inhospitable, and humanity is forced underground. Salvation arrives in the form of a message from the distant planet Iscandar, promising a technology that can cleanse Earth’s radiation. The Yamato, captained by Juuzo Okita and crewed by a band of determined officers including the impetuous but brave Susumu Kodai, must make a perilous journey through hostile space to retrieve this salvation device. Along the way, they face not just merciless enemies but internal struggles, moral dilemmas, and the constant pressure of a ticking clock: the Earth will perish within a year if they fail.

In many ways, Yamato broke the mold for 1970s anime. At a time when most shows were episodic and targeted mainly at children, this series presented serialized storytelling with a complex, continuous narrative arc. This format created genuine dramatic tension and emotional stakes that kept viewers invested episode after episode. While some parts drag with melodrama or technical exposition, the story steadily builds toward a moving climax filled with sacrifice, hope, and bittersweet heroism.

Animation-wise, the series shows its age, with occasionally stiff character movements and production shortcuts like reused backgrounds—typical of 1970s TV budgets. Yet, Leiji Matsumoto’s designs and the Yamato ship itself remain iconic, blending Japan’s wartime history with futuristic sci-fi technology in a compelling aesthetic. The space battles are sweeping and cinematic for the era, supported by Hiroshi Miyagawa’s rousing and emotional musical score, which perfectly balances military pride and somber reflection.

The characters inhabit archetypal but evolving roles. Captain Okita embodies the bushido spirit—noble, self-sacrificing, and burdened by duty—while Kodai matures from impulsive youth to responsible leader molded by loss. Supporting characters bring warmth and conflict, though the presence of women like Yuki Mori reflects dated 1970s gender norms, often limiting them to stereotypical and occasionally objectified roles, which jars against the show’s mature themes.

Beneath its sci-fi veneer, Yamato is a profound meditation on postwar Japanese identity. The revival of the WW2 Yamato as a vessel of salvation symbolizes a desire to transform defeat and shame into hope and renewal. The series navigates the duality of glorifying martial courage while confronting war’s tragic costs. The alien Gamilas are also complex antagonists, featuring honorable figures as well as villains, introducing a nuanced moral landscape rare for its time.

The influence of Space Battleship Yamato on anime is immense and multifaceted. It essentially invented what became the “serious,” serialized sci-fi anime format, making way for legends like Mobile Suit Gundam, which took the treatment of war, politics, and character drama to new levels, and Macross, which played with themes of enemies-turned-allies. Notably, Hideaki Anno, creator of the psychologically rich Neon Genesis Evangelion, cites Yamato as a formative influence, incorporating its emotional and philosophical themes. The series also impacted video games, with elements of its design and story inspiring creators well beyond animation.

The Yamato universe has expanded through numerous sequels, side stories, spin-offs, and remakes. The modern reboot Space Battleship Yamato 2199 is a fan favorite, refreshing the original plot with updated animation and added depth, proving the story’s continued resonance. Other adaptations include OVAs, manga expansions, and a live-action movie, each exploring various facets of the original mythos while bringing Yamato to new audiences.

On the international stage, the series’ English-dubbed adaptation, Star Blazers, was among the first serialized anime to reach Western audiences, planting early seeds for global fandom. Its mature storytelling, serialized arcs, and emotional depth influenced how anime was perceived outside Japan, paving the way for wider acceptance of anime as serious storytelling.

Though the animation style and representations may feel dated now, Yamato’s strengths remain powerful: its epic storytelling, rich themes of sacrifice and renewal, unforgettable characters, and visionary world-building. The show exemplifies how anime can weave thrilling adventure with meaningful thematic exploration, laying groundwork that countless series have followed.

Space Battleship Yamato (1974-1975) stands as a cornerstone of anime history. It transcended its era to become a storytelling template and cultural touchstone whose legacy endures through its influence, spin-offs, and remakes. For fans of sci-fi, anime enthusiasts, and cultural historians alike, it remains an essential watch—a stirring saga of resilience, hope, and the human spirit against cosmic odds.