“You want to put some kind of explanation down here before you leave? Here’s one as good as any you’re likely to find. We’re bein’ punished by the Creator…” — John “Flyboy”

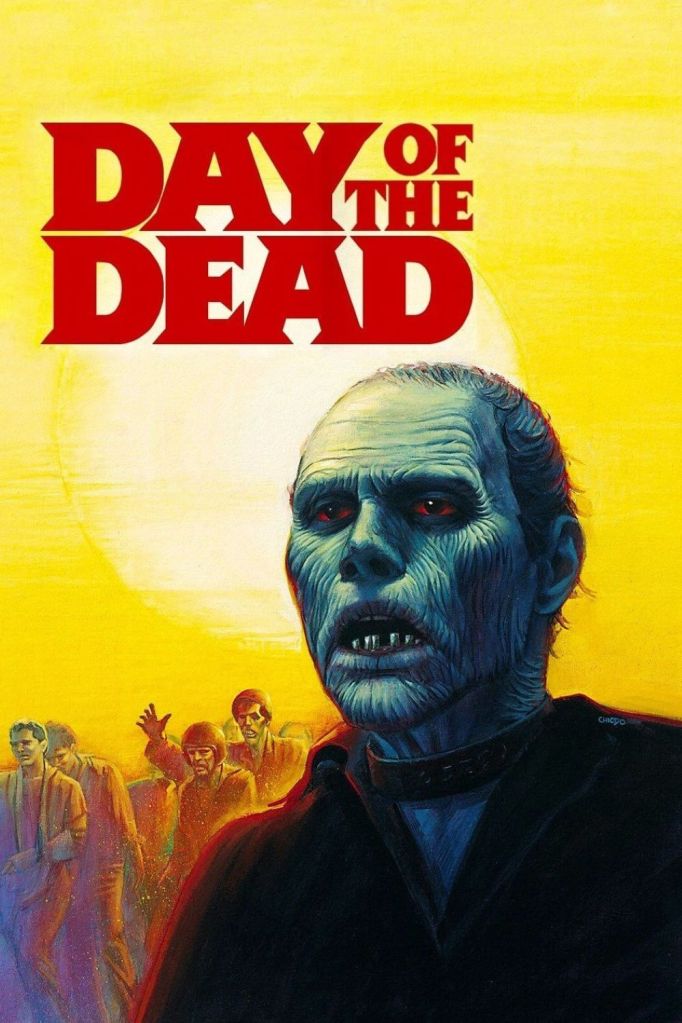

George A. Romero’s 1985 film Day of the Dead stands as an unflinching and deeply cynical meditation on the collapse of society amid a relentless zombie apocalypse, intensifying thematic and narrative complexities first introduced in Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978).

Originally, Romero envisioned the film as an epic, describing it as “the Gone with the Wind of zombie films.” His screenplay featured above-ground scenes and a more expansive narrative, but budget cuts halved the original $7 million budget to $3.5 million, forcing a drastic paredown. While much grandiosity was lost, the trimming resulted in a tighter narrative and heightened the nihilistic tone, deepening the film’s focused exploration of humanity’s darkest aspects during apocalypse.

Set after civilization has collapsed, Day of the Dead places viewers in the suffocating confines of a missile silo bunker in Florida, where scientists and soldiers struggle for survival and solutions amid encroaching undead hordes. The claustrophobic atmosphere—born partly from the abandonment of Romero’s broader original sequences—intensifies the tension between the hopeful scientific pursuit of salvation and the harsh pragmatism of military authority. These competing ideologies escalate into authoritarian violence, embodying the fractured microcosm of a dying society.

Within this claustrophobic world, a third group—composed of characters Flyboy and McDermott—emerges as a stand-in for the rest of humanity. They observe the scientists and soldiers—institutions historically symbols of security and innovation—but witness how these deeply entrenched ways of thinking only exacerbate problems instead of solving them. This third faction characterizes humanity caught between rigid orders and doomed pursuits, reflecting Romero’s broader commentary on societal stagnation and fragmentation.

Central to this conflict are Dr. Logan, or “Frankenstein,” a scientist obsessed with controlling the undead through experimentation, and Captain Rhodes, the hardened soldier who believes survival demands ruthless control.

Logan’s controversial research seeks to domesticate and condition zombies, notably through his most celebrated subject, Bub—the undead zombie capable of rudimentary recognition and emotion—challenging assumptions about humanity and monstrosity.

Here the film benefits greatly from the extraordinary practical effects work of Tom Savini, whose contributions on Day of the Dead are widely considered his magnum opus. Savini’s makeup and gore effects remain unsurpassed in zombie cinema, continually influencing horror visuals to this day. Drawing from his experience as a combat photographer in Vietnam, Savini brought visceral realism to every decomposed corpse and violent injury. The close-quarters zombie encounters showcase meticulous practical work—detailed wounds, biting, and dismemberment—rendered with stunning anatomical authenticity that predates CGI dominance.

Bub, also a masterclass in makeup and animatronics, embodies this fusion of horror and humanity with lifelike textures and movements that blur the line between corpse and creature, rendering the undead terrifyingly believable.

The film captures the growing paranoia and cruelty as resources dwindle—food, ammunition, and medical supplies—and the fragile social order begins to shatter. The characters’ mounting desperation illustrates Romero’s thesis that humanity’s real enemy may be its own incapacity for cooperation.

The moral and social decay is vividly portrayed through characters like Miguel, whose mental breakdown sets destructive events in motion, and Rhodes, whose authoritarian survivalism fractures alliances and moral compass alike. Logan’s cold detachment and experiments push ethical boundaries in a world on the brink.

Romero’s direction combines claustrophobic dread with stark psychological terror, further amplified by Savini’s effects. The cinematography’s low lighting and tight framing create an oppressive environment, while graphic violence underscores a world irrevocably broken. The unsettling sound design—moans, silences, sudden outbreaks—immerses viewers in a relentless atmosphere of decay and fear.

Romero described Day of the Dead as a tragedy about how lack of human communication causes chaos and collapse even in this small slice of society. The dysfunction—soldiers and scientists talking past each other, eroding trust, spirals of paranoia—serves as a bleak allegory for 1980s America’s political and cultural fragmentation. Failed teamwork, mental health crises, and fatal miscommunication thrive as the bunker metaphorically becomes a prison of fractured humanity.

Though not as commercially successful as its predecessors, Day of the Dead remains the bleakest and most nihilistic entry in Romero’s Dead series. Its overall grim tone, combined with mostly unlikable characters, establishes it as the most desolate and truly apocalyptic film of the series. The characters often appear fractured, neurotic, and unable to escape their own destructive tendencies, making the story’s world feel even more hopeless and devastating.

Far beyond a simple gore fest, Day of the Dead serves as a profound social critique infused with psychological depth. It explores fear, isolation, authority abuse, and the ethical limits of science, reflecting enduring anxieties about society and survival. The film’s unsettling portrayal of humanity’s failings, embodied in broken relationships and moral decay, presents a harsh reckoning with what it means to be human when humanity itself is the ultimate threat to its own existence. This thematic complexity, combined with Romero’s unyielding vision and Savini’s unparalleled effects, crafts a chilling and unforgettable cinematic experience.