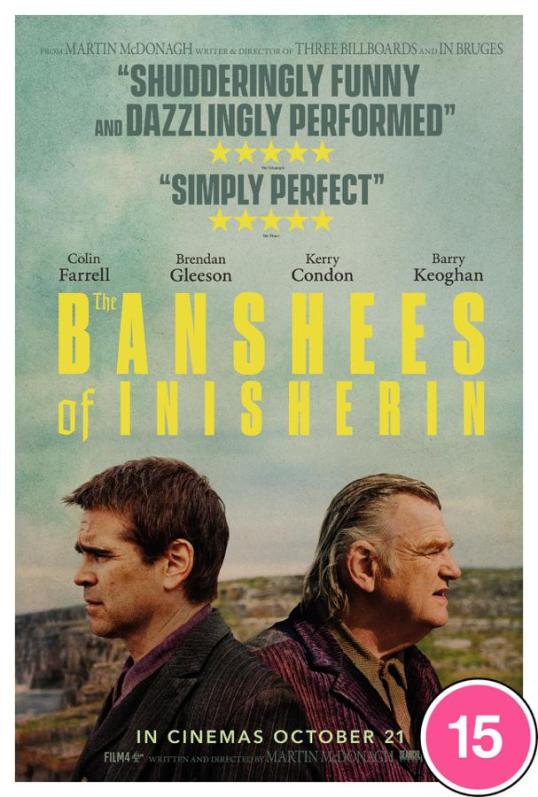

2022’s The Banshees of Inisherin takes place in 1923, near the end of the Irish Civil War.

On the fiction isle of Inisherin, the inhabitants are safe from the the fighting happening on the main land. Occasionally, they can hear the gunfire and the explosions coming from Ireland but, for the most part, they’re content to go about their lives the same as they always have. A few do dream of changing their routine. Young Dominic Kearney (Barry Keoghan) has a crush on Siobhán Súilleabháin (Kerry Condon), who herself occasionally entertains the idea of leaving Inisherin and seeking something better. But, for the most part, everyone is happy with doing the same thing over and over again. They know exactly when they will see each other. They know where everyone will be at any given moment of time. They know that Colm Doherty (Brendan Gleeson) will be playing his fiddle at the pub or sitting in his cottage with his dog. They know that every morning, he will have a drink with his best friend (and Siobhan’s brother), Padraic (Colin Farrell).

Except, one day, Colm abruptly tells Padraic that he no longer wants to be his friend.

Padraic has a difficult time understanding what Colm could possibly mean. He and Colm have always been friends. How can Colm suddenly no longer be his friend? Making things even more frustrating is that Colm refuses to explain what, if anything, Padraic has actually done to make Colm no longer want to be his friend. The closest thing to an explanation that Padraic gets is that Colm finds Padraic to be boring. Colm, who composes music and, at the very least, seems to spend a good deal of time in contemplation, is tired of Padraic’s jokes and his simple ambitions. He’s even tired of hearing about Padraic’s pet donkey, Jenny. In order to show how sincere he is in his desire to no longer speak to Padraic, Colm says that he will chop off one of his fingers every time that Padraic speaks to him. Padaic, who loves to talk and really doesn’t have anyone other than Colm and his sister to talk to, is shocked when fingers start to show up at his home. It only escalates from there.

It’s a darkly funny movie, which is no surprise considering that it was written and directed by Martin McDonagh. If anyone can make you smile while discussing mutilating himself, it’s Brendan Gleeson. At heart, though, The Banshees of Inisherin is a deadly serious film with the characters of Colm and Padraic obviously meant to represent more than just two friends who are no longer speaking. Colm, in his desire to have something more to his life than just his boring life in Inisherin, chops off his fingers and leaves you wondering how he will be able to play the fiddle that he loves so much. It seems counter-productive but once Colm says he’s going to do it, he has no choice but to follow through. The simple-minded but achingly sincere Padraic goes from simply being emotionally wounded to being vengeful over Colm’s rejection. It’s easy to see that Colm originally ended the friendship because he was depressed and feeling as if he had wasted his entire life on Inisherin. Unfortunately, by the time Colm and Padraic come to understand this very common emotion, they’re both too far gone to turn back. While Colm and Padraic go from being friends to sworn enemies, Dominic attempts to be more assertive and Siobhan dreams of perhaps the same thing that motivates Colm, an escape from Inisherin.

The Banshees of Inisherin is a well-acted and thought-provoking film, one that mixes serious of heart-rendering drama with scenes of dark comedy. Brendan Gleeson, Colin Farrell, Barry Keoghan, and Kerry Condon were all Oscar-nominated for their work here. It’s hard to believe that this was Gleeson’s first nomination. (Gleeson lost Supporting Actor to Ke Huy Quan for Everything Everywhere All At Once. I would argue that Gleeson should have been nominated for Best Actor and that he deserved the Oscar over The Whale‘s Brendan Fraser.) Farrell and Gleeson are believable as both lifelong friends and sudden enemies. Farrell delivers his lines with such earnest conviction that he actually brought tears to my eyes.

Despite having received 9 nominations, The Banshees of Inisherin didn’t win in any of its categories, not even for Best Original Screenplay. The Banshees of Inisherin lost Best Picture to Everything Everywhere All At Once, a true Oscar injustice.