Welcome to Retro Television Reviews, a feature where we review some of our favorite and least favorite shows of the past! On Mondays, I will be reviewing Miami Vice, which ran on NBC from 1984 to 1989. The entire show can be purchased on Prime!

This week, we start the fifth and final season of Miami Vice.

Episode 5.1 “Hostile Takeover”

(Dir by Don Johnson, originally aired on November 4th, 1988)

The fifth and final season of Miami Vice gets off to a good start with this episode. After opening with some appropriately glitzy scenes of the drug-fueled Miami nightlife, the episode then shows us that Sonny Crockett is still convinced that he’s Sonny Burnett. He has now returned to Miami and, along with Cliff King (Matt Frewer), he is one of the key advisors to drug lord Oscar Carrera (Joe Santos).

Carrera is at war with El Gato (Jon Polito), the brother of Sonny Burnett’s former employer, Miguel Manolo. El Gato, who wears gold lamé, cries over the body of one of his henchmen, and flinches when forced to deal with direct sunlight, is a flamboyant figure. In fact, he’s so flamboyant that it’s initially easy to overlook how determined he is to get revenge for the death of his brother. That means taking down the Carreras family and Sonny Burnett as well.

The Vice Squad knows that Sonny is moving up in the drug underworld but Castillo is firm when asked what they should do about it. Sonny has an active warrant out for murdering a corrupt cop. “Sonny’s not Sonny anymore,” Tubbs says at one point and Castillo seems to agree.

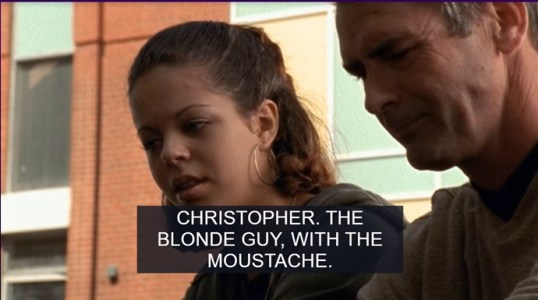

Tubbs goes undercover, making contact with the Carreras cartel. When Sonny meets Tubbs, Tubbs introduces himself as “Ricardo Cooper” and starts speaking in his terribly unconvincing Jamaican accent and that was when I said, “Miami Vice is back!” Sonny doesn’t trust Cooper from the start. “Maybe you’re a cop,” Sonny says. “Not I, mon,” Tubbs replies.

People are dying and, while Sonny doesn’t have a problem with that, the show is also careful to show that Sonny only shoots in self-defense. (It appears the most of the cold-blooded murders are farmed out to Cliff King.) When Oscar Carreras dies, it’s because his poofy-haired son (Anthony Crivello) accidentally shot him when Oscar discovered him with his stepmother. When the son dies, it’s because he was about to shoot Sonny after he caught Sonny with …. his stepmother, again. The Carreras family is so dysfunctional that it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Sonny steps up to take it over.

After promising Castillo that he’ll take out Sonny if necessary, Tubbs meets up with Sonny at beach-side tower. Tubbs looks at Sonny and suddenly says, “Sonny, it’s me, Rico.” Sonny stare at Tubbs. “Do you remember me?” Tubbs asks.

“Sure,” Sonny suddenly says, “You’re Tubbs.”

Three gunshots ring out as the episode ends.

OH MY GOD, DID SONNY KILLS TUBBS!?

We’ll find out next week. For now, I’ll say that — after a disappointing fourth season — this was exactly how Miami Vice needed to start things off for Season 5. Seriously, if you’re going to have Sonny get hit with amnesia, you might as well just go for it and take things to their logical extreme.

Next week …. is Tubbs dead? I hope not, mon.