Welcome to Retro Television Reviews, a feature where we review some of our favorite and least favorite shows of the past! On Wednesdays, I will be reviewing the original Love Boat, which aired on ABC from 1977 to 1986! The series can be streamed on Paramount Plus!

This Week, Captain Stubing is unimpressed by proof that God exists…

This episode had surgery, singing, and supernatural beings who did not impress Captain Stubing. I assume Stubing runs into angels on earth just on his way back from shuffleboard- they’re just old hat to him. There is a sexist and abusive husband Jim Markham (Donny Osmond) married to Lori Markham (Maureen McCormick- He wishes!). Henry Beemus (Henry Gibson) and Charlie Dobbs (Keenan Wynn) are two crooks who want to smuggle gold using nativity figurines and Nuns to unknowingly move the stolen gold through customs – this plot annoyed/tired me; it tannoyed me A LOT. The Nuns were traveling with a choir of Dominican children one of whom was deadly ill, requiring surgery!!! Lastly, an Angel with limitless powers was played by Mickey Rooney.

Jim wanted a traditional wife, but Lori wanted to keep her career. He was abusive even by 1970s standards because everyone wanted to hit him. He kept this bitter storyline going until Lori helped Doc Bricker cut into a Dominican Choir Boy’s throat to allow him to breathe! Yes, The Love Boat became The Mercy Ship!

Questions: why was there no blood on any of the scrubs after the surgery? They cut a hole in a kid’s throat! Then, Jim’s heart was changed because he found out that his wife helped save the Dominican Boy’s life. Hold on, did he not know she was a surgical nurse?! If Jim thinks this was something, wait until your wife tells you about the multiple gang related GSWs she has to treat every Wednesday night!

The Dominican boy’s plotline was interminable and there were great lamentations that his tracheotomy was going to prevent him from singing. Duh! He has a hole in his throat! Along with the throat hole plotline, there were the two thieves Henry and Charlie. These storylines just annoyed me. Mostly, they were just weird foils for Mickey Rooney to work his divine powers.

Speaking of powers, Mickey Rooney’s powers were endless: he healed the Dominican boy, allowing him to sing, he created ornaments out of thin air, he transported matter with his mind, he remade people’s thoughts, and spoke to planets! A fair number of these miracles were witnessed by Captain Stubing and he was as casually impressed as I am when I get a 5 dollar off promotion for Civilization VI on Steam. Captain Stubing barely shrugged.

The episode ended with Mickey Roony’s disembodied animated head atop the ship’s Christmas tree. It was just his head and it winked and smiled at them! Save yourselves! RUN!

There was a lot going on in this episode, but overall it was enjoyable if not hyper-strange.

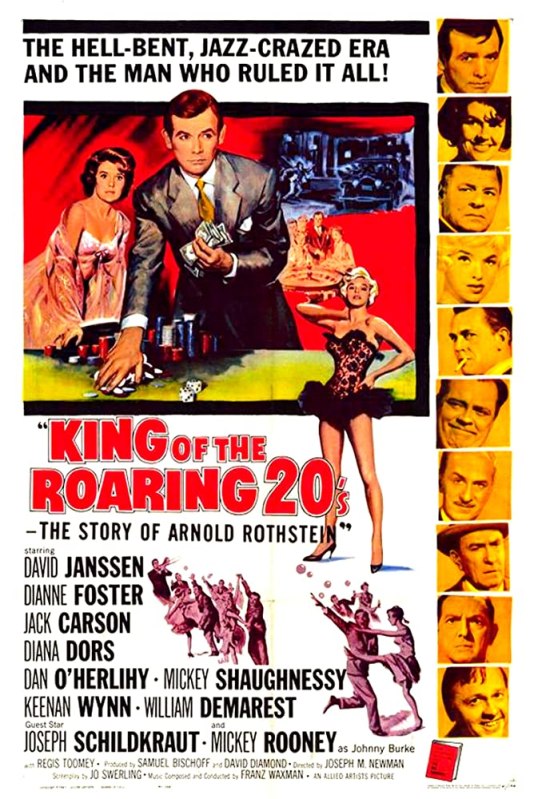

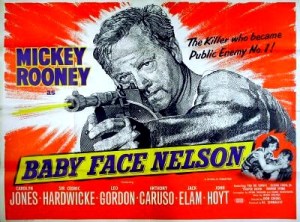

The place is Chicago. The time is the era of Prohibition. The head of the Chicago Outfit, Rocca (Ted de Corsia), has arranged for a career criminal named Lester Gillis (Mickey Rooney) to be released from prison. A crack shot and all-around tough customer, Gillis has only two insecurities: his diminutive height and his youthful appearance. Rocca wants to use Gillis as a hit man but Gillis prefers to rob banks. When Rocca attempts to frame Gillis for a murder, Gillis first guns down his former benefactor and then goes on the run with his girlfriend, Sue Nelson (Carolyn Jones). Because they are both patients of the same underworld doctor (played by Sir Cedric Hardwicke), Gillis eventually meets public enemy number one, John Dillinger (Leo Gordon). Joining Dillinger’s gang, Gillis becomes a famous bank robber and is saddled with a nickname that he hates: Baby Face Nelson.

The place is Chicago. The time is the era of Prohibition. The head of the Chicago Outfit, Rocca (Ted de Corsia), has arranged for a career criminal named Lester Gillis (Mickey Rooney) to be released from prison. A crack shot and all-around tough customer, Gillis has only two insecurities: his diminutive height and his youthful appearance. Rocca wants to use Gillis as a hit man but Gillis prefers to rob banks. When Rocca attempts to frame Gillis for a murder, Gillis first guns down his former benefactor and then goes on the run with his girlfriend, Sue Nelson (Carolyn Jones). Because they are both patients of the same underworld doctor (played by Sir Cedric Hardwicke), Gillis eventually meets public enemy number one, John Dillinger (Leo Gordon). Joining Dillinger’s gang, Gillis becomes a famous bank robber and is saddled with a nickname that he hates: Baby Face Nelson.