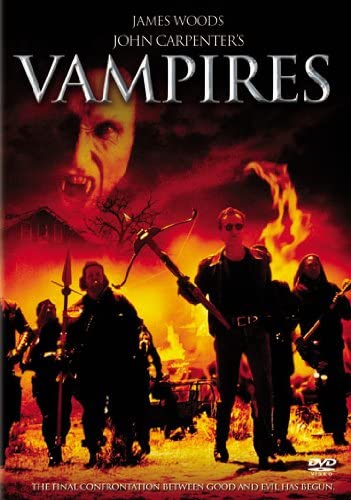

In celebration of the 77th birthday of the great Director John Carpenter, I decided to watch his 1998 film VAMPIRES, starring one of my favorite actors in James Woods. I specifically remember the first time I ever read that this movie was being made and that it would star Woods. It was 1996, and I had just been hired to work for a company called Acxiom Corporation in Conway, Arkansas. It was at this job that I first had access to this new thing called the Worldwide Web. As far as I know, it was the first time I had ever looked at the internet. Of course, I immediately started completing searches on some of my favorite actors, including James Woods, when I came across VAMPIRES as a movie currently in production. These were the first times in my life that I was able to find out about new film projects without looking in a magazine or watching shows like Entertainment Tonight.

In VAMPIRES, James Woods stars as Jack Crow, the leader of team of vampire hunters who get their funding from the Vatican. We’re introduced to the team when they go into a house in New Mexico and proceed to impale and burn a nest of vampires. While the rest of the team celebrates the mission that night in a hotel filled alcohol, drugs, and whores, Jack can’t escape the feeling that something isn’t right, as he doesn’t believe they got the “master vampire” of the group. Unfortunately, Jack is right to worry. As they’re partying, the master vampire Valek (Thomas Ian Griffith) interrupts the fun and proceeds to kill everyone there, with the exception of Jack, his partner Tony (Daniel Baldwin), and Katrina (Sheryl Lee), a prostitute he decided to just bite on. Valek isn’t just a regular old master vampire, either. As it turns out, he’s the original vampire, and he’s on a quest to find the Berziers Cross, an ancient Catholic relic, that will allow him and other vampires to walk in the daylight. Against this backdrop, Jack, Tony, and a priest named Adam (Tim Guinee) use Katrina, who now has a psychic link with Valek, to try to kill the ultimate master vampire Valek, his cleric accomplice Cardinal Alba (Maximillian Schell), and just hopefully, save mankind in the process!

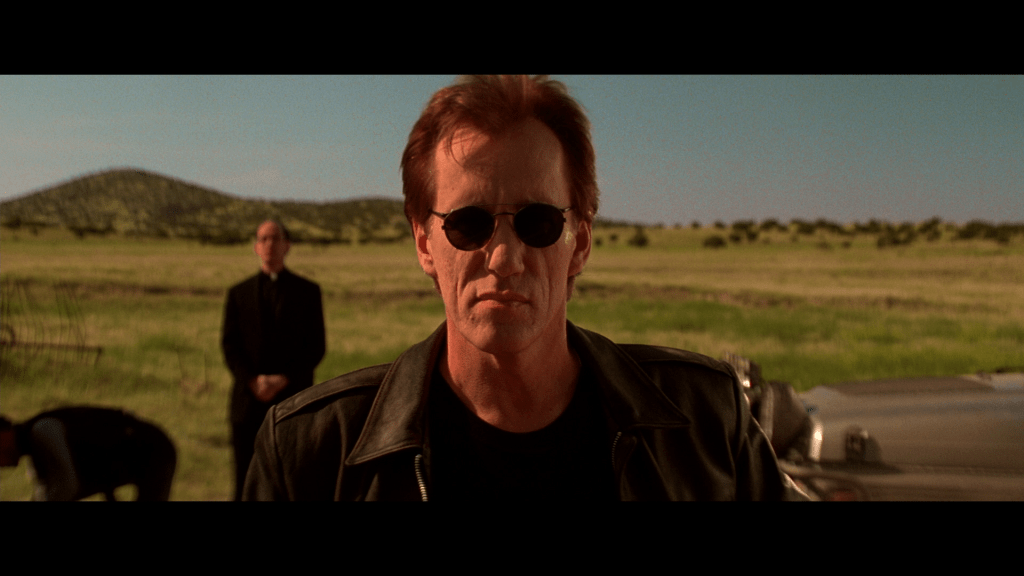

I know that VAMPIRES is not the most well-known or beloved John Carpenter film. He’s done so many great movies, but VAMPIRES is special to me as it was the first of his films that I ever saw in the movie theater. And the opening 30 minutes of the film is as badass as it gets. Carpenter is a master of the set-up. There’s lots of slow motion as Carpenter’s guitar riffs rock the soundtrack and the camera moves in on James Woods, with his cool sunglasses and black leather jacket, just before his team goes in and destroys a vampire nest at the beginning of the film. I also think the set-up of Thomas Ian Griffith as Valek is awesome, as he strolls up to the hotel room while the vampire hunters celebrate, completely unaware of the carnage about to befall them. Griffith has never looked cooler than he did in his long black coat and long hair, both blowing in the wind. These were awesome moments that illustrated Carpenter’s ability to project a sense of visual cool and power that I was mesmerized with. I wanted to see what happens next. And as a 25-year-old man at the time of VAMPIRE’s Halloween release in 1998, I also gladly admit that I really enjoyed the beauty of a 31-year-old Sheryl Lee. I would have definitely done everything I could do to save and protect her. The remainder of the film may have not been able to keep the same momentum as those first 30 minutes, but it’s a solid, enjoyable film, buoyed by the intense performance of Woods!

There are several items of trivia that interest me about VAMPIRES:

- John Carpenter had a good working relationship with James Woods on the set, but they had a deal: Carpenter could film one scene as it is written, and he would film another scene in which Woods was allowed to improvise. The deal worked great, and Carpenter found that many of Woods’ improvised scenes were brilliant.

- VAMPIRES was John Carpenter’s only successful film of the 1990’s. Its opening weekend box office of $9.1 million is the highest of any John Carpenter film.

- The screenplay for VAMPIRES is credited to Don Jakoby. Jakoby has some good writing credits, including the Roy Scheider film BLUE THUNDER (1983), the Cannon Films “classic” LIFEFORCE (1985), and the Spielberg produced ARACHNAPHOBIA (1990). The reason Don Jakoby interests me, however, is the fact that he had his name removed from the film I’ve seen more than any other, that being DEATH WISH 3 (1985), starring Charles Bronson. Even though Jakoby provided the script for DEATH WISH 3, due to the drastic number of changes, Jakoby insisted his name be removed. The script is credited to the fake “Michael Edmonds” instead.

- As I was typing up my thoughts on VAMPIRES today, I learned of the death of the director David Lynch. This brings special poignancy to the fact that John Carpenter cast Sheryl Lee after seeing her on Lynch’s T.V. series TWIN PEAKS (1990).

- Frank Darabont, who directed one of the great films of all time, THE SHAWSHANK REDEMPTION (1994), has a cameo as “Man with Buick.” Fairly early in the film, after Crow, Montoya, and Katrina crash their truck escaping the hotel massacre, they encounter the man at a gas station and forcefully take the Buick. This is a strong sign of just how respected John Carpenter was by other great filmmakers at the time.

John Carpenter has directed some absolute classics like ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 (1976), HALLOWEEN (1978), ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (1981), THE THING (1982), and BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA (1986). There’s no wrong way to celebrate a man who has brought such joy into our lives through his work. Today, I’m just thankful that he has been given the opportunity to share his talents with us!