“The world isn’t run by weapons anymore, or energy, or money. It’s run by little ones and zeroes, little bits of data. It’s all just electrons.” — Cosmo

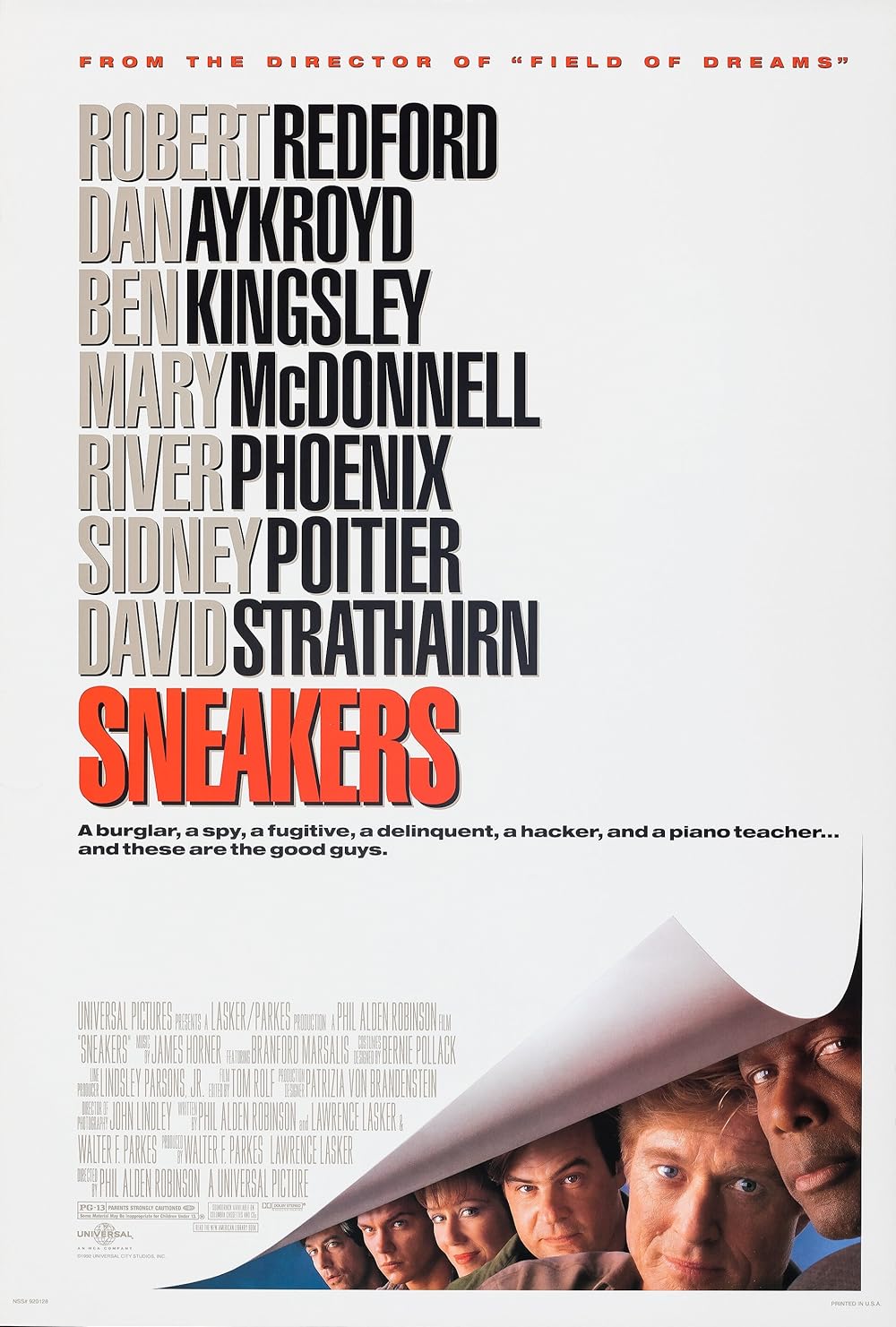

Sneakers is one of those early-’90s studio thrillers that feels oddly cozy for a movie about global surveillance and information control. It plays like a hangout movie that just happens to revolve around a world-breaking black box, and whether that balance works for you will pretty much decide how much you click with it.

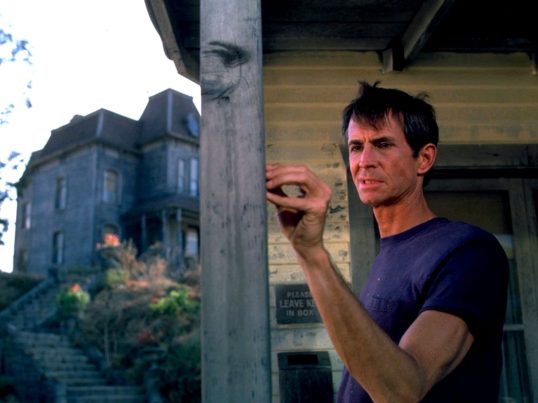

Set in San Francisco, Sneakers follows Martin Bishop (Robert Redford), a one-time radical hacker now leading a boutique team that gets paid to break into banks and corporations to test their security. When a pair of supposed NSA agents lean on him about a skeleton in his past, they strong-arm him into stealing a mysterious “black box” from a mathematician, which turns out to be a codebreaker capable of cracking pretty much any system on Earth. From there, the crew gets pulled into a bigger conspiracy involving shady figures and high stakes, with Martin confronting echoes from his activist days.

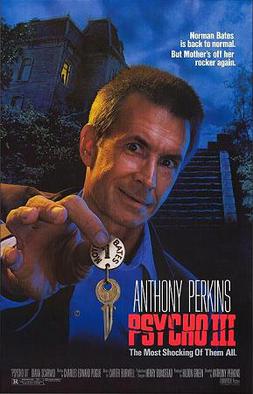

The first thing that jumps out about Sneakers is the cast, which is frankly stacked even by modern standards. Redford brings an easy, weathered charm to Bishop; there’s a low-key joke baked into the movie that this legendary leading man is now playing a guy who looks like he spends more time worrying about his back pain than saving the world, and it works. He’s surrounded by a motley crew: Sidney Poitier’s ex-CIA operative Crease, Dan Aykroyd’s conspiracy-addled tech nut Mother, David Strathairn’s blind audio savant Whistler, and River Phoenix’s eager young hacker Carl. Mary McDonnell rounds things out as Liz, Martin’s ex, who gets roped back into his orbit and ends up doing some of the film’s most memorable social-engineering work.

What makes this lineup click—and really shine—is how effortlessly the ensemble works together, especially with Robert Redford and Sidney Poitier anchoring it as the team’s leaders. Redford’s Bishop is the steady, pragmatic brain, always one step ahead but grounded by his regrets, while Poitier’s Crease brings that sharp-edged authority from his CIA days, barking orders with a mix of gruffness and loyalty that keeps everyone in line. Their dynamic is electric: you get these moments where Bishop’s quiet scheming bounces off Crease’s no-nonsense intensity, like when they’re coordinating a break-in and trading barbs mid-scheme, and it sells the years of trust they’ve built. It elevates the whole group, giving the younger or quirkier members—Mother’s wild theories, Whistler’s uncanny ears, Carl’s fresh energy—a solid foundation to riff off, turning what could be chaos into a tight, believable unit. Phil Alden Robinson directs the film almost like an ensemble comedy interrupted by bursts of espionage, so the banter and the little grace notes between jobs end up being as memorable as the heists themselves. There’s a looseness to the way the team bickers, teases, and riffs on each other that sells the idea they’ve been doing this for years, long before the plot kicked in. You feel that especially in scenes where they’re all huddled around some piece of tech or puzzling out a clue; the script allows them to overlap, crack side jokes, and be fallible instead of treating them like slick super-spies who never misstep.

Tonally, the movie walks an interesting line. On one hand, this is very much a tech thriller about the power of information, with the ominous “Setec Astronomy” anagram (“too many secrets”) tying it all together. On the other, this is a film where an extended sequence revolves around tricking a socially awkward engineer on a date so they can steal his voice patterns and credentials, and the whole thing plays like a romantic caper more than anything. Robinson leans hard into suspense in key stretches—most notably toward the end, where tension builds through clever set pieces involving motion sensors, improvised skills, and closing threats—but even then the movie never loses its sense of mischief.

That playfulness can be both a strength and a limitation. The upside is obvious: Sneakers is fun. It’s easy to watch, easy to rewatch, and it rarely drowns you in jargon for the sake of sounding smart. Instead, it abstracts the tech into clear stakes—this box breaks codes, this system controls money and power—so you always understand the “why” behind every scheme even if you don’t follow every “how.” The downside is that, for a movie nominally about the terrifying implications of a universal decryption key, it doesn’t dig as deeply into the horror of that idea as it could. It gestures at themes of privacy, state overreach, and the weaponization of data, but it’s more interested in using those ideas as a playground than as something to rigorously interrogate.

Viewed from 2026, the tech is obviously dated—landlines, old terminals, magnetic cards—but that almost works in the film’s favor now. There’s a retro-futurist charm to seeing characters talk about “ones and zeroes” and the power of information as if they’re whispering forbidden knowledge, when today that conversation is basically the nightly news. At the time, the film was praised for being ahead of the curve on the idea that whoever controls data controls everything, and you can still feel that prescience. The irony is that what was once cutting-edge has softened into a kind of warm nostalgia, which might be why the movie has quietly settled into cult-favorite status rather than staying in the mainstream conversation.

On a craft level, the movie is sturdy across the board. John Lindley’s cinematography keeps things bright and clean rather than shadow-saturated, which reinforces that lighter tone; San Francisco looks lived-in and slightly mundane, not like a glossy cyber-noir playground. James Horner’s score is a big asset: a jazz-inflected, airy sound that gives scenes a sense of cool rather than danger, which again nudges things toward caper more than hard thriller. It’s the kind of soundtrack that sneaks into your head and quietly sets the mood without demanding too much attention, and a lot of fans single it out as one of his more underappreciated efforts.

If there’s a major weak spot, it’s probably in how the film handles its big ideas and antagonists. The central conflict draws on ideological clashes from the characters’ pasts, but it mostly serves as a charismatic foil rather than a fully fleshed-out debate. The story doesn’t push too hard on challenging cautious pragmatism versus radical change, or probe deeply into who benefits from the status quo. For a tale built on “too many secrets,” the moral landing feels predictable rather than revelatory.

The film also shows its age in how it uses certain characters, especially Liz and Carl. McDonnell gets moments to shine—her date with Werner Brandes is a highlight—but Liz is often pushed to the side once the plot machinery gets going, which is a shame given the sparks between her and Redford. River Phoenix’s Carl is similarly underused; he’s the young blood in a team of older pros, and you can see hints of a more emotionally grounded arc there, but the film keeps him mostly in comic-relief mode. It doesn’t derail the movie, but it does contribute to the sense that Sneakers is more interested in being a breezy ensemble hang than in fully developing everyone it introduces.

Still, it’s hard to deny the movie’s overall charm. The central heist beats are cleanly staged, the reversals are satisfying without being overcomplicated, and the script gives almost every member of the team at least one clutch contribution so it feels like a true group effort. The later stretches cleverly tie together the tech setup and character dynamics, ending on a light coda that underscores the film’s affection for its quirky crew over global intrigue.

As for how it holds up, Sneakers isn’t an untouchable classic, but it’s a very easy film to recommend if you have any affection for ’90s thrillers, ensemble casts, or tech-adjacent stories that don’t drown you in circuitry diagrams. Some of its politics feel glib, some of its gadgets are charmingly antique, and its big questions about Information Age ethics are more backdrop than deep dive. But the film’s mix of laid-back humor, light suspense, and grounded, slightly rumpled characters gives it a distinct flavor that a lot of modern, hyper-slick hacker movies lack.

If you go in wanting a serious, hard-edged exploration of cyber-warfare and state power, Sneakers will probably feel like it’s only skimming the surface. If you’re in the mood for a smart, lightly twisty caper that lets you spend two hours with a killer cast tossing around clever dialogue amid escalating capers, it’s still a very satisfying watch.