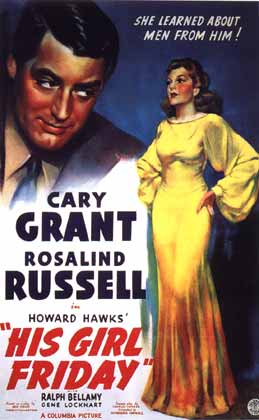

The 44th film in Mill Creek’s Fabulous Forties box set was the classic 1940 comedy, His Girl Friday.

Earlier this week, when I mentioned that Cary Grant’s Oscar-nominated work in Penny Serenade was not the equal of his work in comedies like The Awful Truth and The Philadelphia Story, quite a few people took the time to let me know that their favorite Cary Grant film remains His Girl Friday. And I can’t blame them. Not only does His Girl Friday feature Cary Grant at his best but it also features Rosalind Russell at her best too. Not only that but it’s also one of the best films to ever be directed by the great Howard Hawks. There are a lot of career bests to be found in His Girl Friday, and that’s not even counting a supporting cast that is full of some of the greatest character actors of the 1940s.

The film itself is a remake of The Front Page, that classic story of an editor trying to keep his star reporter from leaving the newspaper in order to get married. (Along the way, they not only manage to expose municipal corruption but also help to hide and exonerate a man who has escaped from death row.) The action moves fast, the dialogue is full of quips, and the whole thing is wonderfully cynical about … well, everything. The major difference between The Front Page and His Girl Friday is that the reporter is now a woman and she’s the ex-wife of the editor. When Cary Grant’s Walter Burns attempts to convince Rosalind Russell’s Hildy Johnson to cover just one last story, he’s not only trying to hold onto his star reporter. He’s also trying to keep the woman he loves from marrying the decent but boring Bruce Baldwin.

Bruce, incidentally, is played by Ralph Bellamy. Bellamy also played Grant’s romantic rival in The Awful Truth. To a certain extent, you really do have to feel bad for Ralph. He excelled at playing well-meaning but dull characters. As played by Bellamy, you can tell that Bruce would be a good husband in the most uninspiring of ways. That’s the problem. Hildy deserves more than just a life of boring conformity and Walter understands that. Not only do Walter and Hildy save the life of escaped convict Earl Williams but, in doing so, Hildy is also saved from a life of being conventional.

As we all know, it’s fashionable right now to attack the news media. Quite frankly, modern media often makes it very easy to do so. For that matter, so do a lot of a movies about the media. To take just two of the more acclaimed examples, there’s a smugness and a self-importance to both Good Night and Good Luck and Spotlight that becomes more and more obvious with each subsequent viewing. (Admittedly, Edward R. Murrow was prominent way before my time but, if he was anything like the pompous windbag who was played by David Strathairn, I’m surprised that television news survived.) Far too often, it seems like well-intentioned filmmakers, in their attempt to defend the media, end up making movies that only serve to remind people why the can’t stand the old media in the first place.

Those filmmakers would do well to watch and learn from a film like His Girl Friday. His Girl Friday is a cheerfully dark film that is full of cynical journalists who drink too much and have little use for the type of self-congratulation that permeates through a film like Spotlight. Ironically, you end up loving the journalists in His Girl Friday because the film never demands that you so much as even appreciate them. There are no long speeches about the importance of journalism or long laments about how non-journalists just aren’t smart enough to appreciate their local newspaper. Instead, these journalists are portrayed as hard workers and driven individuals who do a good job because deliberately doing anything else is inconceivable. They don’t have time to pat themselves on the back because they’re too busy doing their job and hopefully getting results.

If you want to see a film that will truly make you appreciate journalism and understand why freedom of the press is important, watch this unpretentious comedy from Howard Hawks.

In fact, you can watch it below!