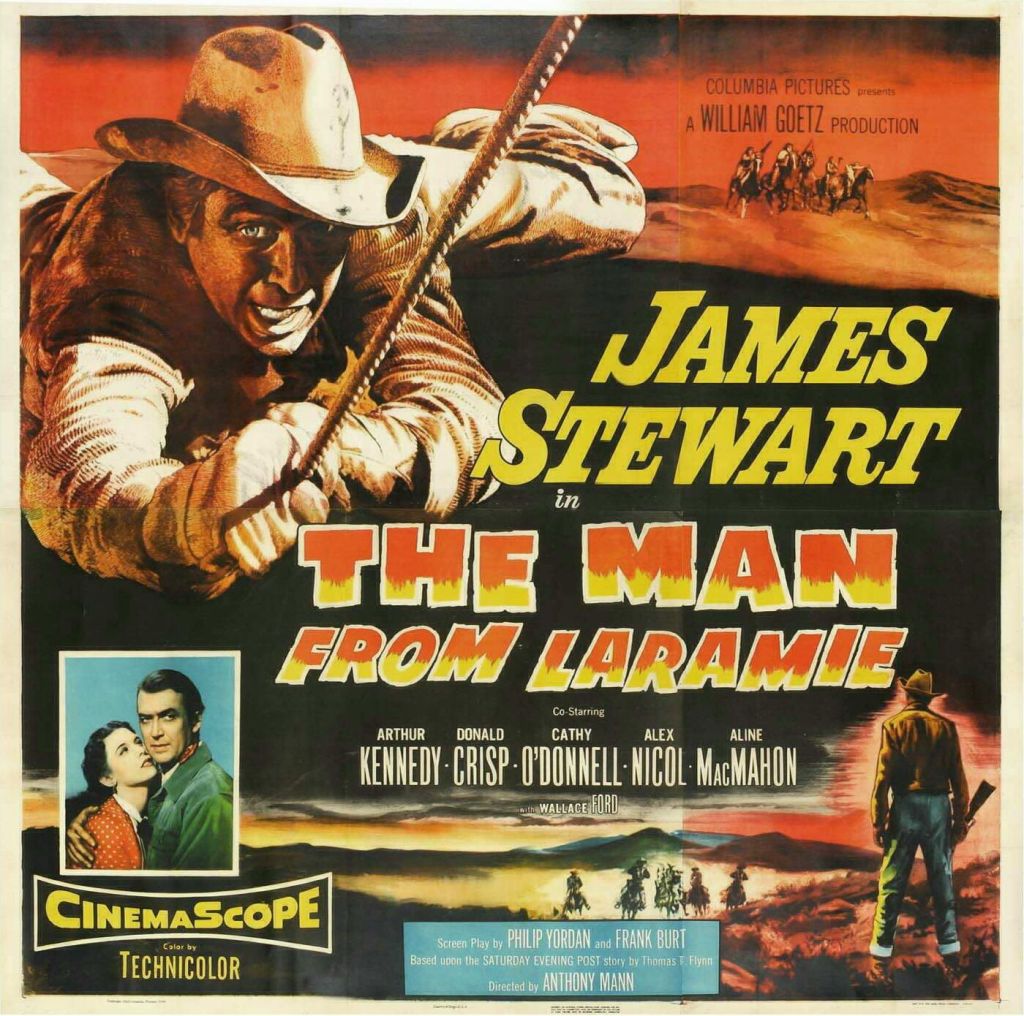

Happy Birthday, Jimmy Stewart!

I’m celebrating Jimmy Stewart’s birthday by watching his western THE MAN FROM LARAMIE! Stewart plays Will Lockhart, a man who has run into some bad luck. His brother, a U.S. cavalryman, was recently killed in an attack by Apaches using repeating rifles outside of the town of Coronado, New Mexico. In an attempt to track down the man who sold the rifles to the Indians, Lockhart has come to Coronado from Laramie, WY, to snoop around. He’s welcomed to town by Dave Waggoman (Alex Nicol), we’ll call him “Crazy Dave,” the son of powerful local rancher Alec Waggoman (Donald Crisp). Accusing Lockhart of stealing salt off of their land, Crazy Dave proceeds to drag him with a rope, burn his wagons and shoot his mules. Before he can do even more damage to Lockhart, the foreman of the Waggoman ranch Vic Hansbro (Arthur Kennedy) comes along and stops him. Vic seems like a reasonable man, but he does ask Lockhart to move on down the trail before there’s any more trouble. Lockhart isn’t leaving until he finds out more about those rifles so he politely declines by going back into town, finding Crazy Dave, and kicking his ass. He then goes to see Alec and asks to be paid back for the wagons and mules that crazy Dave destroyed. Alec pays Lockhart back and then calls Vic in to come see him. Here’s where we start to get a feel for Waggoman family dynamics. You see, Alec loves his son no matter how crazy he is, and he expects Vic to keep him out of trouble. He even takes the cost of the destroyed wagons and dead mules out of Vic’s pay instead of Crazy Dave’s. We find out that Crazy Dave is jealous of Vic, and that Vic feels underappreciated by a man he has treated like a father for many years. Against this backdrop of family jealousy and insanity, Lockhart will continue to dig around until he finds out who sold the rifles that killed his brother. Could it be Vic or Crazy Dave?

THE MAN FROM LARAMIE is the last of five westerns that Stewart worked on under the direction of Anthony Mann. Their work is legendary, including the western classics WINCHESTER ‘73 (1950), BEND OF THE RIVER (1952), THE NAKED SPUR (1953), and THE FAR COUNTRY (1954). In my opinion, they may have saved their best for last. Jimmy Stewart gives a masterful performance in the role of Will Lockhart. Stewart was very smart in the way he played his parts in westerns. Tall and gangly, he would never have been a believable western star if he had played his roles more like a John Wayne or Gary Cooper. Rather, his character here is driven by an uncontrollable desire for revenge, so no matter what happens to him, outside of being killed, he’s going to keep on coming. In this movie, he’s dragged, beaten and even has his hand shot from point blank range, but that doesn’t stop him. And every so often he flashes that Jimmy Stewart smile and you can’t help but have complete sympathy for him. The supporting performances are good as well, especially from Donald Crisp as Alec Waggoman and Arthur Kennedy as Vic Hansbro. Neither are completely bad men, but they make bad decisions based on emotions that most of us can completely understand. They’re so good in the roles that we can’t help but kinda like them in spite of those bad decisions. One of the things I love about old westerns is the way they deal with honest emotions and universal truths. At one point in the film, after discovering that Vic has lied to him about something, Alec tells him, “Once you start lying, there’s no way to stop!” If you’ve ever lied about something before, you know that one lie always leads to another, and then to another. The drama in THE MAN FROM LARAMIE centers around what happens to the characters when the truth finally comes to light. In my opinion it’s great stuff, and produces one of my very favorite westerns!

On a side note, I love this movie so much that I demanded that my wife and I stop and eat in Laramie a couple of years ago when we were visiting family in Wyoming. Here’s a pic from that wonderful day. I wanted to make sure we got the sign in the back that said Laramie!