“An idea, a feeling became clear to me. The hunter did not hate the wolf. The wolf did not hate the sheep. But violence felt inevitable between them. Perhaps, I thought, this was the way of the world. It would hunt you and kill you just for being who you are.” — the Creature

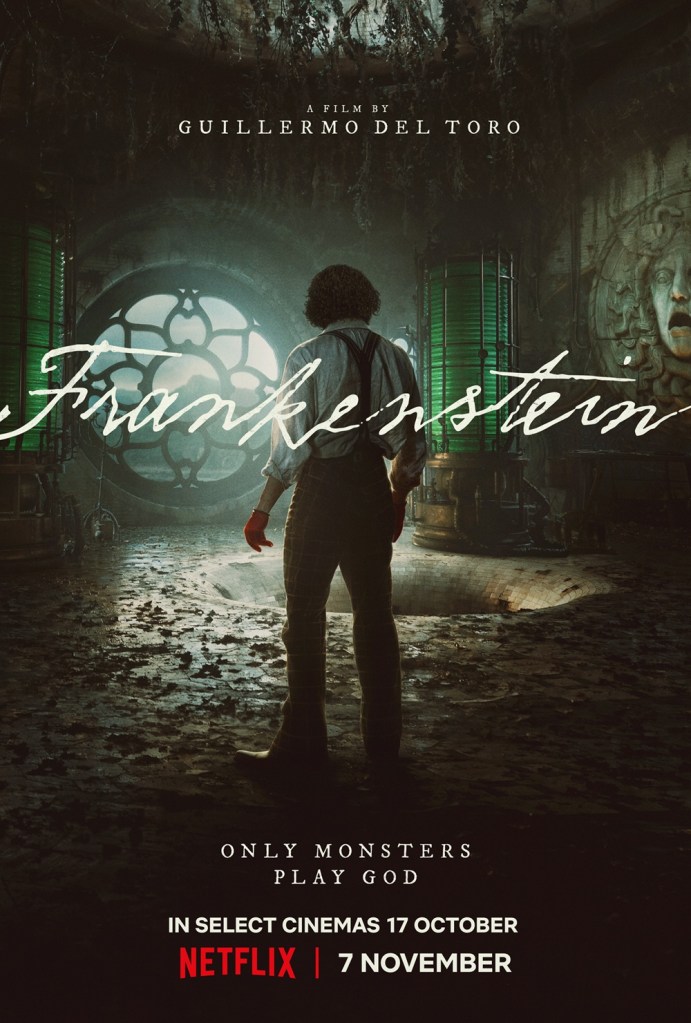

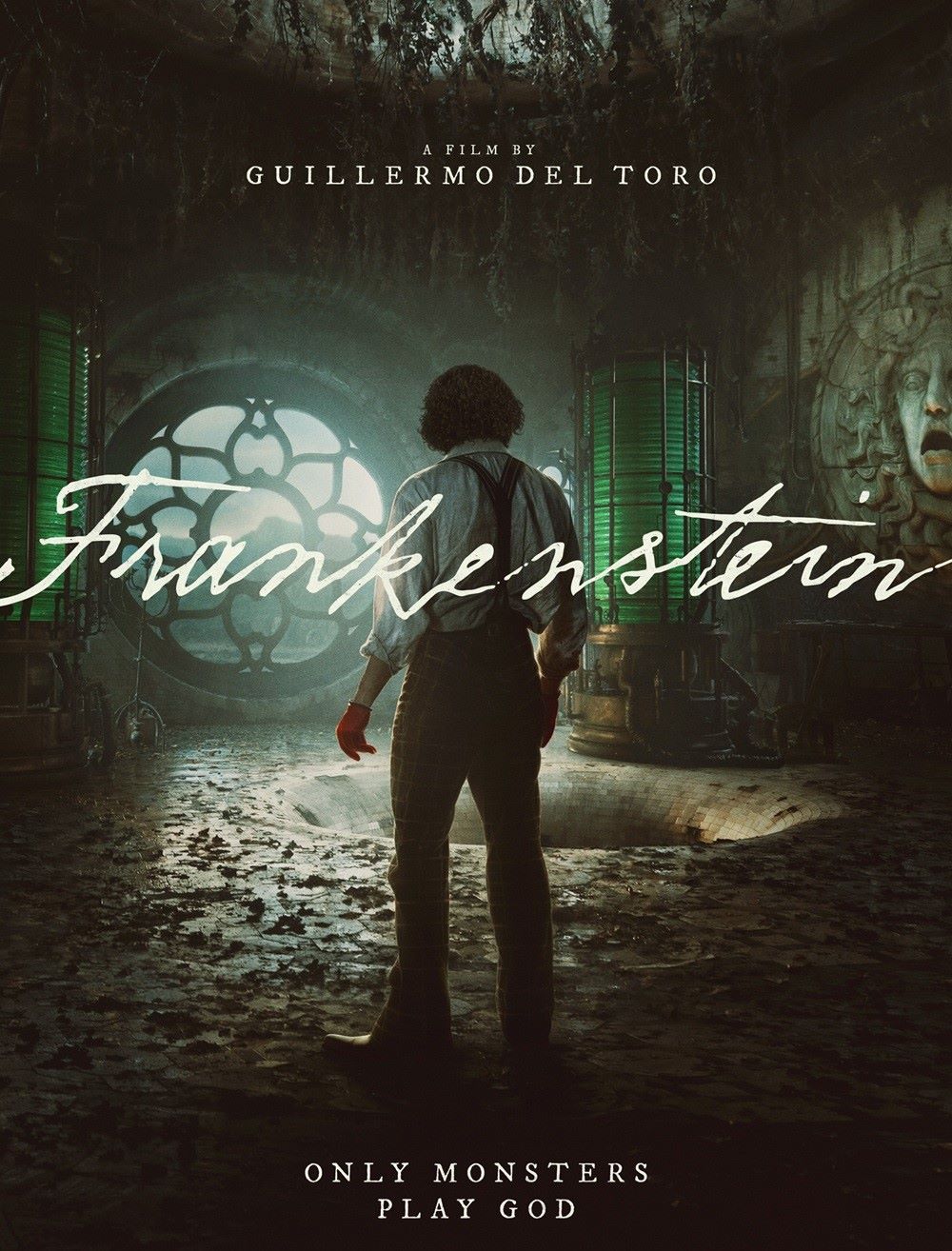

Guillermo del Toro’s long-awaited take on Frankenstein finally lumbers to life after years of speculation and teases, and it’s every bit the dark, hypnotic fever dream you’d expect from his imagination. The film, a Netflix-backed production running close to two and a half hours, stars Oscar Isaac as the guilt-ridden Victor Frankenstein and Jacob Elordi as his tragic creation. The result lands somewhere between Gothic melodrama and spiritual lament—a lush, melancholy epic about fathers, sons, and the price of neglect. It’s both a triumph of aesthetic world-building and a case study in overindulgence, the kind of movie that leaves you haunted even when it occasionally tests your patience.

From the very first frame, del Toro plunges us into a Europe steeped in rot and beauty. His world feels more haunted than alive—every misty street lamp and echoing corridor loaded with centuries of decay. Victor, introduced as both a visionary and a failed son, is shaped by years of cruelty at the hands of his domineering father, played with aristocratic venom by Charles Dance. That upbringing lingers in every decision he makes, especially when he turns to science to defy death. Del Toro shoots his laboratory scenes as though they were sacred rituals: the flicker of candlelight reflecting off glass jars, the close-up of trembling hands threading sinew into flesh. When the Creature awakens, lightning cracks like some divine act of punishment. It’s a birth scene that feels more emotional than monstrous—Elordi’s raw, wordless confusion gives it a painful tenderness that lingers longer than the horror. Del Toro discards the usual clichés of flat heads and neck bolts, opting for something far more human: an imperfect body full of scars and stitched reminders of mortality.

One of the most striking choices del Toro makes is reframing Victor and the Creature as mirror images rather than opposites. Instead of playing Victor as a simple mad scientist, del Toro paints him as a broken man desperate to reclaim the control he never had as a child. That fear and obsession ripple through the Creature, who becomes his unacknowledged shadow—an extension of Victor’s failure to love or take responsibility. The movie often frames the two in parallel shots, their movements synchronized across different spaces, suggesting that creator and creation are locked in a tragic loop. The audience watches both sides of the story—Victor’s guilt and the Creature’s anguish—without clear moral lines. This emotional split gives the film its heartbeat: the Creature isn’t a villain so much as a rejected child, articulate and lonely, begging to know why he was made to suffer.

Jacob Elordi’s performance is revelatory. He channels something hauntingly human beneath the layers of prosthetics and makeup. There’s a fragility to the way he moves—those long, uncertain gestures feel less like a monster testing its strength and more like someone trying to exist in a world that never wanted him. His eyes carry the movie’s emotional weight; the moment he sees his reflection for the first time is quietly devastating. Oscar Isaac, meanwhile, leans hard into Victor’s manic idealism, all sweat-soaked ambition and buried grief. He makes the character compelling even at his most despicable, though at times del Toro’s dialogue spells out Victor’s torment too bluntly. Still, the scenes between them—particularly their tense reunion in the frozen north—achieve the Shakespearean tragedy that del Toro clearly aims for.

Visually, Frankenstein is pure del Toro—sumptuous, grotesque, and alive in every corner of its composition. Each frame looks painted rather than filmed: flickers of gaslight reflecting on wet marble, glass jars filled with organs that seem to breathe, snow settling gently on slate rooftops. The film feels drenched in the texture of another century, yet vibrates with modern energy. Costume designer Kate Hawley, longtime collaborator of del Toro, deserves special recognition here. Her work helps define the story’s emotional tone, dressing Victor in meticulously tailored waistcoats that hint at obsession through precision, and the Creature in tattered fabrics that seem scavenged from several lives. Elizabeth’s gowns chart her erosion from warmth to mourning, using color and texture as silent narration. Hawley’s palette moves from opulent golds and creams to bleak greys and winter blues—visually tracing how ambition and grief drain the light from these characters’ worlds. The costumes, much like del Toro’s sets, feel alive with history, heavy with stories stitched into every seam.

Mia Goth gives a strong, if underused, turn as Elizabeth, Victor’s doomed fiancée. Her early scenes bring a spark of warmth to the story’s coldness; her later ones turn tragic in ways that push Victor toward his final breakdown. Minor characters—the townspeople, the academics, the curious aristocrats who toy with Victor’s discovery—carry familiar del Toro trademarks: grotesque faces, eccentric manners, glimmers of compassion buried in callousness. The composer’s score matches this tone perfectly, alternating between aching melodies on piano and surging orchestral crescendos that make even the quiet scenes feel mythic. Combined, the sound and visuals give Frankenstein a grandeur that most modern horror films wouldn’t dare attempt.

Still, not every gamble lands cleanly. Del Toro’s interpretation leans so hard into empathy that it dulls the edges of the original story’s moral conflict. Shelley’s Creature grows into a murderous intellect, acting out of vengeance as much as sorrow; here, his violence is softened or implied, as though del Toro can’t quite bring himself to stain the monster’s purity. The effect is powerful emotionally but flattens some of the tension—Victor becomes the clear villain, and the Creature, the clear victim. It fits del Toro’s worldview but leaves the viewer missing some ambiguity. The pacing also falters in the middle third. There are long, ornate monologues about divinity, creation, and guilt that blur together into a swirl of purple prose. The visuals never lose their grip, but the script occasionally does, especially when it slows down to explain what the imagery already tells us.

Those fits of overexplanation aside, del Toro’s Frankenstein stays deeply personal. The story connects directly to the themes he’s mined for years: innocence cursed by cruelty, love framed in pain, beauty stitched from the broken. The Creature isn’t just man made from corpses; he’s a kind of prayer for grace—a plea for understanding in a world defined by rejection. Victor’s failure to nurture becomes an act of spiritual cowardice rather than scientific arrogance. The parallels between them give the film its emotional voltage. Every time one character suffers, the other feels it by proxy, as if their bond transcends life and death.

By the final act, all the grand tragedy is distilled into the silence between two beings who can’t forgive each other—but can’t let go, either. The closing image of the Creature, trudging across a barren arctic plain beneath a rising sun, borders on mythic. His tear-streaked face and quiet acceptance of solitude bring the story full circle: a being born of man’s arrogance chooses forgiveness when his maker couldn’t. It’s sad, tender, and surprisingly spiritual, hinting at del Toro’s constant fascination with mercy in a cruel universe.

As a whole, Frankenstein feels like the culmination of del Toro’s career obsessions condensed into one sprawling film. It’s not perfect—it wanders, it sermonizes, and it sometimes sacrifices fear for sentiment—but it’s haunted by sincerity. You can see del Toro’s fingerprints in every gothic curve and crimson hue, and even when he overreaches, you believe in his conviction. Isaac anchors the film with burning intensity, Elordi gives it wounded humanity, and Goth tempers the heaviness with grace.

In the end, this version of Frankenstein isn’t about horror in the traditional sense. It’s not there to make you jump—it’s there to make you ache. The film trades sharp scares for bruised hearts, replacing terror with empathy. Del Toro reanimates not just flesh but feeling, dragging one of literature’s oldest monsters into our modern reckoning with parenthood, grief, and the burden of creation. It’s daring, messy, and undeniably alive. For better or worse, it’s exactly the Frankenstein Guillermo del Toro was always meant to make.