Welcome to Retro Television Reviews, a feature where we review some of our favorite and least favorite shows of the past! On Wednesdays, I will be reviewing the original Love Boat, which aired on ABC from 1977 to 1986! The series can be streamed on Paramount Plus!

This week, we have a special two-hour episode!

Episodes 6.18 and 6.19 “Isaac’s Aegean Affair/The Captain and The Kid/Poor Rich Man/ The Dean and the Flunkee”

(Dir by Alan Rafkin, originally aired on February 5th, 1983)

The Love Boat is going to Greece!

This is another one of those two-hour Love Boat episodes. The crew is assigned to work a Greek cruise. Love and sight-seeing follow. Isaac, for instance, falls in love with a passenger named Reesa (Debbie Allen) and even resigns from the crew so that he can spend the rest of his life in Greece with her. Unfortunately, Isaac forgets to ask Reesa ahead of time and, when Isaac returns to Reesa’s Greek flat, he discovers that she had reconciled with her husband (James A. Watson, Jr.). It’s back to the Love Boat for Isaac!

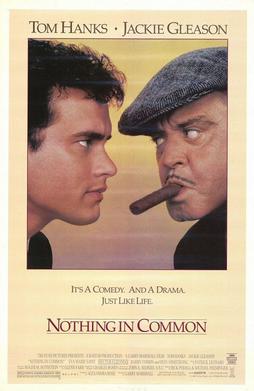

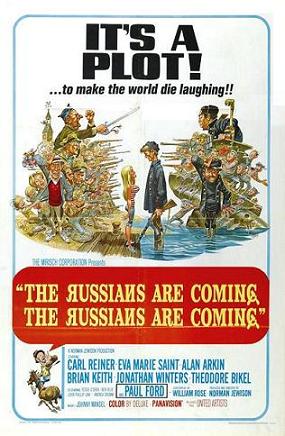

Meanwhile, the graduating class of Captain Stubing’s old college is holding their graduation ceremony at the ruins of a Greek temple. The class valedictorian (Jameson Parker) give a speech in which he shows appreciation to his Greek aunt (Eva Marie Saint), even though he’s discovered that she’s not as a wealthy as he originally assumed she was. The Dean (Eddie Albert) is finally convinced to give a makeup exam to a student (Leigh McCloskey) who missed his history final. A teacher (Shirley Jones) finally agrees to marry the dean. And Vicki briefly falls in love with a 16 year-old prodigy (Jimmy McNichol) and she gets engaged to him for about an hour or two. Captain Stubing wonders how Vicki would be able to continue her education if she got married. I’m wondering how she’s continuing her education while living and working on a cruise ship.

There was a lot going on in this episode but the true star of the show was the Greek scenery. This episode was filmed on location and, as such, it’s basically a travelogue. Fortunately, Greece looks beautiful! Seriously, the 2-hour, on-location episodes of The Love Boat must have been a blast to shoot.

This week? This week was probably a 10 out of 10 on the How Coked Up Was Julie Scale but hey, she was in Greece. She had every right to live a little.

Now, I want to take a cruise!