What is Murphy’s Law?

What is Murphy’s Law?

Let’s ask LAPD Detective Jack Murphy.

“Don’t fuck with Jack Murphy.”

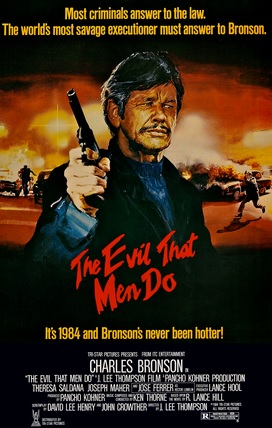

Normally, having a law named after you would be pretty cool but it appears that this is just a law that Jack came up with himself. Having to come up with your own law is kind of like having to come up with your own nickname. Dude, it’s just lame. Since Jack Murphy is played Charles Bronson, we can cut him some slack.

Murphy’s Law was one of the many film that, towards the end of his career, Bronson made for Cannon Films. He played a detective in almost all of them. Jack Murphy is Dirty Harry without the fashion sense. He is also an alcoholic who cannot get over his ex-wife (Angel Tompkins) and her decision to become a stripper. Not only has Murphy managed to piss off his superiors with his bad attitude but the mob is out to get him. Everyone has forgotten Murphy’s Law. Everyone is fucking with Jack Murphy.

Jack’s main problem, though, is Joan Freeman (Carrie Snodgress). Years ago, Murphy sent Joan to prison for murder but, because it’s California and Jerry Brown appointed all of the judges, Joan gets out after just a few years. Joan starts to systematically murder everyone that Murphy knows, framing Murphy for the murders. Murphy’s arrested by his fellow cops, all of whom need a refresher on Murphy’s Law. Though handcuffed to a young thief (Kathleen Wilhoite), Murphy escapes from jail and set off to remind everyone why you don’t fuck with Jack Murphy.

Murphy’s Law is a typical Cannon Bronson film: low-budget, ludicrously violent, borderline incoherent, so reactionary than it makes the Dirty Harry films look liberal, and, if you’re a fan of Charles Bronson, wildly entertaining. Bronson was 65 years old when he played Jack Murphy so he cannot be blamed for letting his stunt double do most of the work in this movie. What’s interesting is that, for once, Bronson is not the one doing most of the killing. Instead, it is Carrie Snodgress, in the role of Joan Freeman, who gets to murder nearly the entire cast. There is nothing subtle about Snodgress’s demonic performance, which makes it perfect for a Cannon-era Bronson film. In fact, Carrie Snodgress gives one of the best villainous performances in the entire Bronson filmography. There is never any doubt that Snodgress is capable of killing even the mighty Charles Bronson, which makes Murphy’s Law a little more suspenseful than most of the movies that Bronson made in the 80s.

Whatever else can be said about Murphy’s Law, it does feature one of Bronson’s best one liners. When Joan threatens to send him to Hell, Murphy replies, without missing a beat, “Ladies first.” Only Bronson could make a line like that sound cool. That’s Bronson’s Law.

Joe Bomposa (Rod Steiger) may wear oversized glasses, speak with a stutter, and spend his time watching old romantic movies but don’t mistake him for being one of the good guys. Bomposa is a ruthless mobster who has destroyed communities by pumping them full of drugs. Charlie Congers (Charles Bronson) is a tough cop who is determined to take Bomposa down. When the FBI learns that Bomposa has sent his girlfriend, Jackie Pruit (Jill Ireland), to Switzerland, they assume that Jackie must have information that Bomposa doesn’t want them to discover. They send Congers over to Europe to bring her back. Congers discovers that Jackie does not have any useful information but Bomposa decides that he wants her dead anyway.

Joe Bomposa (Rod Steiger) may wear oversized glasses, speak with a stutter, and spend his time watching old romantic movies but don’t mistake him for being one of the good guys. Bomposa is a ruthless mobster who has destroyed communities by pumping them full of drugs. Charlie Congers (Charles Bronson) is a tough cop who is determined to take Bomposa down. When the FBI learns that Bomposa has sent his girlfriend, Jackie Pruit (Jill Ireland), to Switzerland, they assume that Jackie must have information that Bomposa doesn’t want them to discover. They send Congers over to Europe to bring her back. Congers discovers that Jackie does not have any useful information but Bomposa decides that he wants her dead anyway.

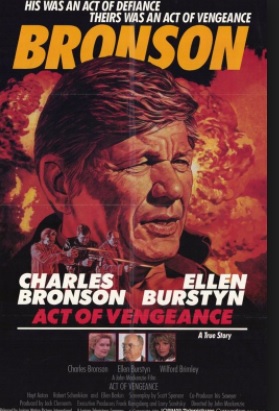

Act of Vengeance is an uncompromising look at union corruption and how it hurts the workers while benefitting the bosses.

Act of Vengeance is an uncompromising look at union corruption and how it hurts the workers while benefitting the bosses. Charles Bronson, man.

Charles Bronson, man.

What is Murphy’s Law?

What is Murphy’s Law? It’s Bronson and Delon, trapped in an airless vault!

It’s Bronson and Delon, trapped in an airless vault!