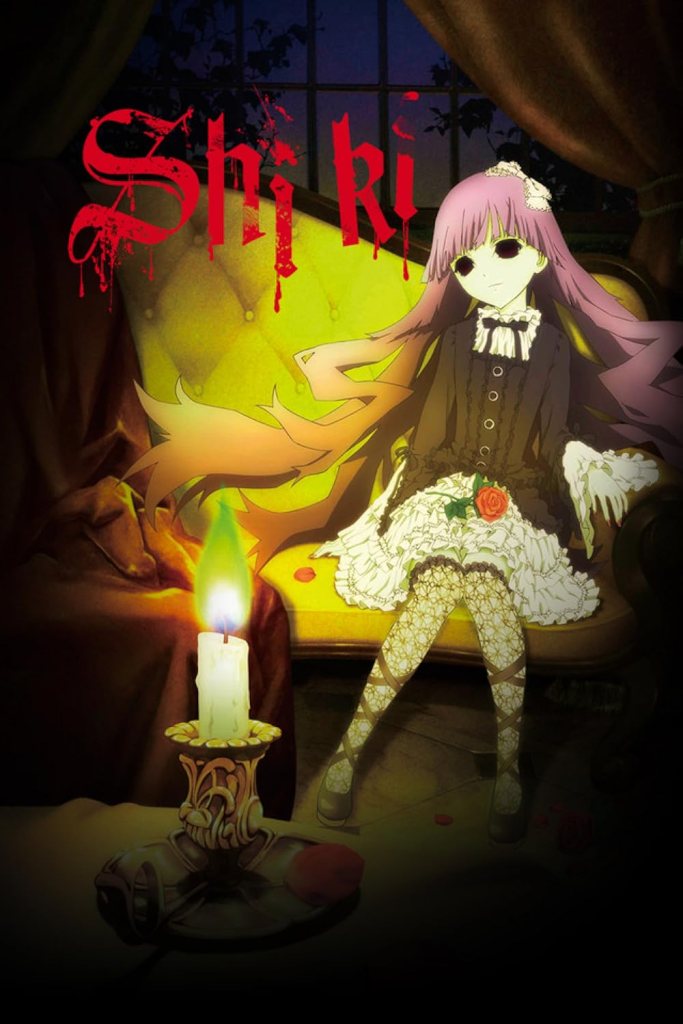

The anime adaptation of Shiki, based on Fuyumi Ono’s acclaimed horror novel and directed by Tetsurō Amino, stands as a rare specimen in the horror genre. Rather than relying on quick shocks, excessive gore, or typical jump scares, Shiki unsettles its audience through atmosphere, moral erosion, and the slow, relentless unraveling of human conscience. Premiering in 2010, the series unfolds at a measured, almost meditative pace, transforming what could have been a simple vampire tale into a profound meditation on survival, faith, fear, and the delicate boundary between life and death when everything is pushed to the brink.

The story is set in Sotoba, a small, isolated village nestled precariously near a larger modern metropolis. The residents of Sotoba live tightly woven lives, their routines and social bonds preserved with careful attention over generations. This fragile peace shatters when a mysterious wave of deaths begins sweeping through the population. At first, these fatalities are dismissed as consequences of the harsh local climate—heatstroke, seasonal illnesses, and the inevitable toll of old age. Yet, as the body count rises, the truth reveals itself to be much darker: the deceased are rising as vampires, known locally as “shiki” or “corpse demons,” creatures that survive by feeding on the living.

What distinguishes Shiki from many other vampire narratives is its refusal to paint the conflict in stark black-and-white terms of good versus evil. The shiki are portrayed not as mindless monsters but as tormented souls, burdened by memories, emotions, and guilt over what they have become and the horrors they must commit to survive. Conversely, the human villagers—once caring and close-knit neighbors—succumb to suspicion, fear, and eventually cold-hearted survival instincts. The real horror emerges as morality frays and the line between human and monster becomes irrevocably blurred.

Unlike classic horror tales set in small towns—such as Stephen King’s ’Salem’s Lot, where a seemingly idyllic village hides sinister supernatural forces—Shiki offers a nuanced inward gaze. For instance, the novel They Thirst situates vampirism within a sprawling urban landscape, where anonymity accelerates chaos and alienation. In contrast, Shiki uses the microcosm of Sotoba to emphasize intimate, communal decay. The focus is not just on the physical threat, but on the erosion of social bonds and moral fabric, revealing how fragile human civility truly is under stress.

While ’Salem’s Lot depicts vampires as a pure evil contaminating a tight-knit community—highlighting themes of moral corruption and contamination—Shiki explores moral ambiguity with far greater depth. The vampires, including the enigmatic Sunako Kirishiki, retain their memories, emotions, and even remorse. Both vampires and humans carry guilt and anguish, complicating simplistic notions of villainy. The villagers—their friends, family, and neighbors—begin to see the suffering of the vampires while realizing their own brutal deeds. The narrative challenges viewers to question whether survival excuses the loss of morality or if it is possible to retain one’s spirit even amid brutal chaos.

At the heart of the series are characters who embody competing moral philosophies. Natsuno Yuki, a cynical teenager newly transplanted to Sotoba from the city, provides both an insider and outsider’s perspective. His disillusioned view highlights how fear, suspicion, and grief can unravel even the most intimate relationships. Natsuno serves as a rational voice within a community unraveling into paranoia and despair, offering a reflection of the audience’s own struggle to comprehend the incomprehensible.

Dr. Toshio Ozaki exemplifies the desperate human desire for order amid chaos. Initially, he seeks to explain away the deaths with rational, scientific explanations grounded in medicine. However, when superstition and supernatural realities intrude, Ozaki is compelled to confront truths beyond his understanding. His leadership in trying to save Sotoba begins with scientific resolve but soon descends into moral compromise. As hysteria spreads, the villagers’ collective violence explodes into ruthless slaughter, justified as necessary to preserve survival. Ozaki’s internal conflict—balancing ethical convictions against brutal necessity—reflects the series’ central question: at what point does the will to survive erode the soul?

Set against this turmoil is Sunako Kirishiki, the quiet yet profoundly troubled leader among the shiki. Though she has lived for centuries and suffers deeply from a sense of divine rejection—believing God has forsaken her—Sunako retains a core spirituality that anchors her sense of morality. Even as she is forced to kill in order to survive, she wrestles with guilt and her faltering faith. Her belief that divine rejection is not synonymous with divine abandonment acts as a form of moral defiance, preserving her fragile humanity amid brutal circumstances.

This spiritual resilience is deepened through her relationship with Seishin Muroi, a local junior monk and published author. Muroi, gentle and introspective, offers a unique perspective on the tragedy unfolding in Sotoba. His dual roles as a religious figure and a thoughtful writer allow him to interpret the crisis with spiritual depth and philosophical insight. His literary works—admired by the Kirishiki family, especially Sunako—explore mortality, suffering, and the search for meaning beyond pain. As a monk, Muroi embodies faith and compassion; as an author, he grapples with existential ambiguities, granting him a rare wisdom in navigating the village’s descent.

Muroi’s role makes him both observer and actor in Sotoba’s unraveling. His spiritual duties compel him to provide comfort and guidance, while his writings deepen his understanding of human and supernatural suffering. This duality shapes his interactions with Sunako and others, serving as a pathway for faith and empathy to endure amid horror and despair.

Sunako’s friendship with Muroi becomes central to her moral endurance. In contrast to Tatsumi, the Kirishiki family’s pragmatic and ruthless jinrō guardian who views survival through a cold, utilitarian lens, Muroi offers a moral counterpoint grounded in mercy and hope. Through his compassionate presence and reflective insights, Sunako finds a way to renew her faith. Although she feels forsaken, Muroi’s influence rekindles the fragile spark of belief in her that prevents her humanity from being swallowed by despair.

The thematic contrast between Muroi and Tatsumi becomes a fulcrum for Shiki: survival devoid of soul versus survival with spirit. Muroi’s continuing faith—soft, tentative, but persistent—demonstrates that even in the bleakest conditions, moral conviction need not fade entirely. His dual lens as monk and author enriches the narrative, bridging theology and philosophy while threading through the story’s core existential dilemmas.

Amino’s direction amplifies these themes through patient pacing and subtle storytelling. The mounting tension grows slowly through quiet, contemplative moments and lingering visuals—the hum of cicadas, shifting light through leaves, the barely audible footsteps in the dark. Ryu Fujisaki’s stylized character designs convey unease with elongated features and a surreal sheen, while Yasuharu Takanashi’s sparse, mournful score melds choral lamentations with haunting silences. Together, these elements create an immersive atmosphere steeped in dread and melancholy.

By the series’ climax, the distinction between human and shiki dissolves into near indistinguishability. Both sides bear the scars of survival—physical, psychological, and spiritual. The violence ceases, but the damage lingers, leaving survivors hollow, burdened by guilt and loss. Yet amidst the ruins of a shattered community, Sunako’s renewed faith, forged under Muroi’s guidance, flickers faintly—an emblem of hope that refuses to be extinguished.

The final scene distills this weighty truth without grandiosity or closure. There are no victors, no absolutes—only profound loneliness in survival. The living bear wounds deeper than any inflicted by fang or bullet. But in this quiet aftermath, Sunako’s fragile faith, buoyed by Muroi’s steadfast compassion, pulses as the last vestige of what it means to remain human: choosing faith and empathy even when everything else seems lost.

Shiki closes not with resolution but with a haunting reminder: survival is incomplete without humanity, and faith—however delicate—is the courage to hold onto that humanity when all else has fallen away.