There are A LOT of bad horror films out there and I mean Halloween Resurrection bad, but when you get a truly great one, it sticks with you for your life. This movie is more unique in that the writer Alex Garland really peaked with this film and there are IMDB credits to prove it. Danny Boyle directed the piece and you really feel as though you were inhabiting the after-times of a dead world….well, undead. Danny Boyle did Trainspotting, Slumdog Millionaire, 127 hours, but I know what you’re thinking- Did he write anything besides family films for Disney? Yes, he made this awesome zombie film.

We see shots of terrible violence and realize that monkeys are being forced to watch it. Then, Animal Rights Activists enter heavily armed with guns and sanctimony. The researcher begs them not to release the animals because they are infected with a terribly contagious disease and that the goal of their research is to find a cure for rage. The Animal Rights Activists patiently listen to the scientist instead of acting purely from smug instinct, dooming us all. Just kidding, they release one of the monkeys, it rips the animal rights activist apart, barf bleeds all over her, making her patient zero, and I try really hard not to root for the diseased monkey. The disease is out! Of course, many of us always knew that animal rights activists would lead to the zombie apocalypse. Just read their twitter feeds and you’ll know that they’ll doom us all. Fade to Black and 28 Days Later… appears as a subtitle in the bottom right….BRILLIANT!!!

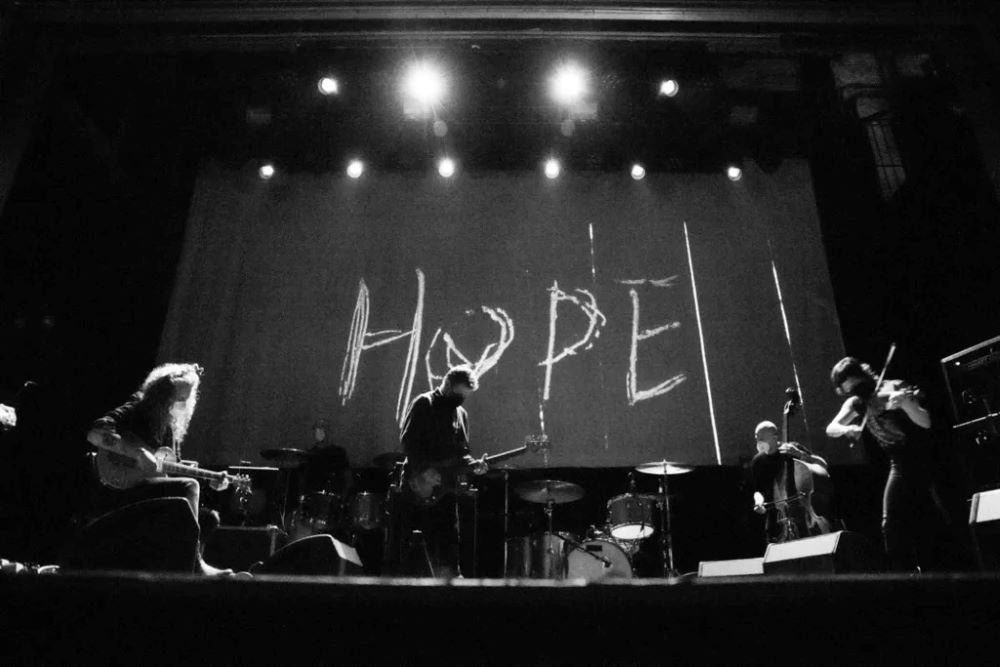

Jim wakes from a coma to a dead world. Sound familiar? Yes, TWD went beyond homage there. He leaves the hospital to amazing details that really sell a dead London. Empty hospital, empty streets, garbage, worthless cash everywhere, a bus is overturned in front of parliament, and an amazing score reveals a World without people. If you’re looking for the song that plays when he’s walking around dead London during the opening – it’s by Godspeed You! Black Emperor – East Hastings – Long Version.

HOW DID THEY MAKE LONDON EMPTY? MERLIN! This is England, after all. Nah, Danny Boyle got MANY government officials to agree to let the production shutdown huge traffic arteries for 90 seconds at a time. London is one my most favorite cities and I would love to live there and it is Europe’s New York City, therefore, imagine shutting down Times Square for filming.

Jim gets chased by fast-moving zombies and meets Selena and a Red Shirt. He goes with them and realizes very quickly that he was probably better off in a coma. Jim insists on seeing his parents. They agree to take him and he finds them suicided on the bed clutching a note that reads- “With endless love, we left you sleeping. Now, we’re sleeping with you. Don’t wake up.” This is not your dad’s zombie movie. They decide to stay at his house for the night, but are attacked by zombies. Red Shirt gets infected and is dispatched by Selena. Jim and Selena must flee.

Jim and Selena venture forth and find Frank and his daughter Hannah. It hasn’t rained for some time, therefore -no water. For survival, they have to leave the city. Selena doesn’t want to go with Frank and his daughter because she sees them as anchors, but Jim insists and Hannah explains that we actually need each other. Frank plays a radio signal that beckons them to safety and they leave as one tribe. Along the way, there are some intense scenes and some shopping. They arrive at the salvation location, but Frank gets infected and is killed by soldiers.

Right away, you can tell that the soldiers are goofing off too much. I have commanded soldiers and there’s some level of goofing off, but this had an air of creepiness and broken discipline. The soldier’s have taken over a residence as their HQ and have put up defenses to keep zombies out and people in. We quickly learn that the radio message was a trap. Corporal Mitchell harasses Selena and a fight erupts. The Major breaks it up, but it’s clear that Jim, Hannah, and Selena are prisoners. The Major explains that the soldiers could not face a dead world and one attempted suicide. The Major had a plan- lure women to the compound with a radio signal. When they arrived, they would keep them prisoner to breed with his soldiers to restart civilization. He puts it simply: women equal hope. His logic and delivery is truly chilling in its cold mathematics.

They decide to execute Jim and a SGT who gets in their way and keep Hannah and Selena for reproduction. Corporal Mitchell and another Soldier take Jim and the SGT out for execution to a killing field. Corporal Mitchell wants to bayonet Jim, the other Soldier can’t handle that kind of intimate murder, leading to a melee. The SGT is killed and Jim escapes.

The next sequence is truly amazing because we see our hero morph from the sensitive man that he is naturally to a state of feral revenge indistinguishable from the fast-moving zombies. He’s shirtless to further emphasize his lack of civility as he makes short work of many of the soldiers to rescue Hannah and Selena. Corporal Mitchell who wanted to bayonet him and rape Selena becomes the focal point of Jim’s rage- Jim puts his thumbs deep into Corporal Mitchell’s eyes until he’s dead. This is a critical act of monstrosity because it shows not tells in the clearest finality that there is no separation between Jim’s blind rage and the rage that has infected the human population.

I don’t want to totally spoil the ending because this film will remain with you and is a must see. It’s commentary on violence and society is forever salient: Violence is horrific, but forced civilization is worse and will lead to the ultimate act of revenge – THUMBS IN YOUR EYEBALLS or some such equivalent. The other important lesson the film tries to inculcate is to beware of self-certain sanctimonious people because their grandiosity could doom us all.