The Columbus Film Critics Association has announced its picks for the best of 2025. The winners are listed in bold.

Best Film

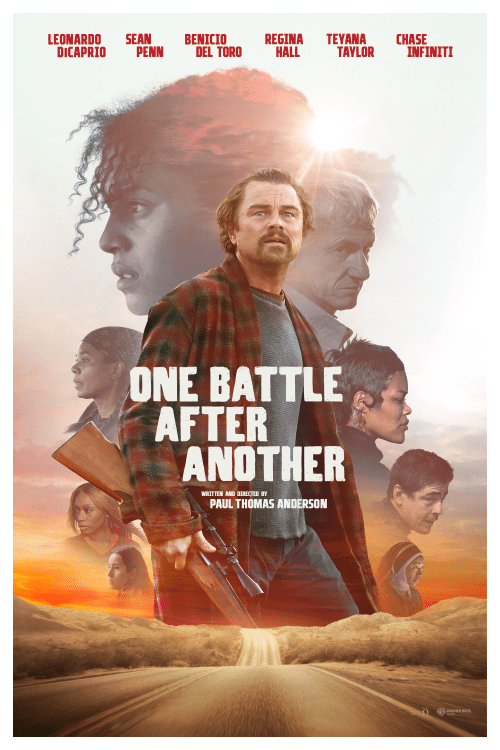

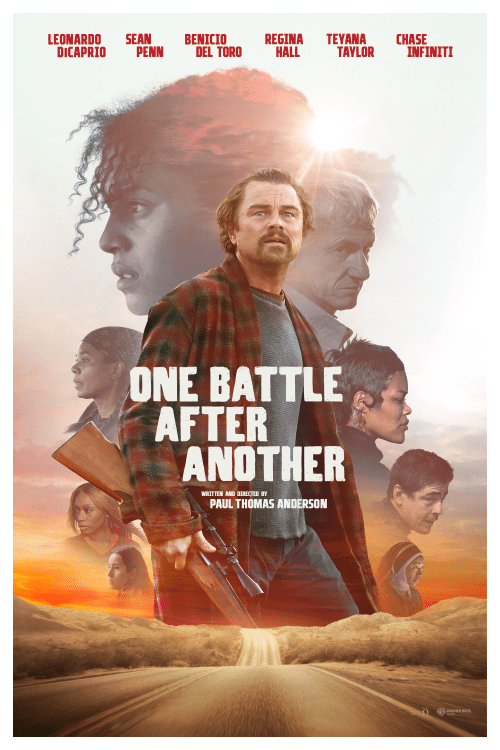

1. One Battle After Another

2. No Other Choice

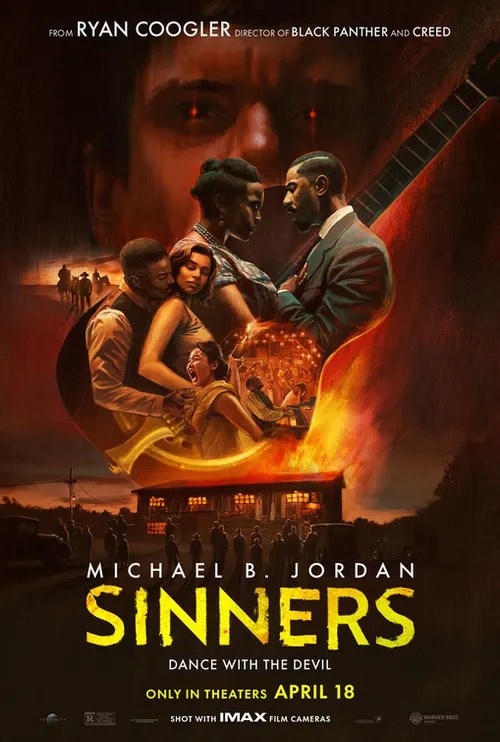

3. Sinners

4. It Was Just an Accident

5. Bugonia

6. Wake Up Dead Man

7. Sentimental Value

8. Train Dreams

9. Weapons

10. Marty Supreme

11. Frankenstein

Best Director

Paul Thomas Anderson, One Battle After Another (WINNER)

Ryan Coogler, Sinners (RUNNER-UP)

Rian Johnson, Wake Up Dead Man

Jafar Panahi, It Was Just an Accident

Josh Safdie, Marty Supreme

Best Lead Performance

Jessie Buckley, Hamnet (RUNNER-UP)

Rose Byrne, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You

Timothée Chalamet, Marty Supreme

Leonardo DiCaprio, One Battle After Another

Joel Edgerton, Train Dreams

Ethan Hawke, Blue Moon (WINNER)

Chase Infiniti, One Battle After Another

Michael B. Jordan, Sinners

Wagner Moura, The Secret Agent

Jesse Plemons, Bugonia

Renate Reinsve, Sentimental Value

Emma Stone, Bugonia

Best Supporting Performance

Benicio Del Toro, One Battle After Another (WINNER)

Jacob Elordi, Frankenstein

Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, Sentimental Value

Delroy Lindo, Sinners

Amy Madigan, Weapons

Wunmi Mosaku, Sinners

Sean Penn, One Battle After Another (RUNNER-UP)

Adam Sandler, Jay Kelly

Stellan Skarsgård, Sentimental Value

Teyana Taylor, One Battle After Another

Best Ensemble

It Was Just an Accident

Marty Supreme

One Battle After Another (WINNER)

Sinners (RUNNER-UP)

Wake Up Dead Man

Actor of the Year (For an Exemplary Body of Work)

Josh Brolin, The Running Man, Wake Up Dead Man, and Weapons

Benicio Del Toro, One Battle After Another and The Phoenician Scheme (RUNNER-UP)

Josh O’Connor, The History of Sound, The Mastermind, Rebuilding, and Wake Up Dead Man (WINNER)

Amanda Seyfried, The Housemaid and The Testament of Ann Lee

Emma Stone, Bugonia and Eddington

Breakthrough Film Artist

Odessa A’zion, Marty Supreme (Acting)

Miles Caton, Sinners (Acting)

Chase Infiniti, One Battle After Another (Acting) (WINNER)

Carson Lund, Eephus (Directing and Screenwriting)

Eva Victor, Sorry, Baby (Acting, Directing, and Screenwriting) (RUNNER-UP)

Best Cinematography

Autumn Durald Arkapaw, Sinners (WINNER)

Michael Bauman, One Battle After Another (RUNNER-UP)

Dan Laustsen, Frankenstein

Claudio Miranda, F1

Adolpho Veloso, Train Dreams

Łukasz Żal, Hamnet

Best Film Editing

Ronald Bronstein and Josh Safdie, Marty Supreme

Andy Jurgensen, One Battle After Another (WINNER)

Stephen Mirrione, F1 (RUNNER-UP)

Joe Murphy, Weapons

Michael P. Shawver, Sinners

Best Adapted Screenplay

Paul Thomas Anderson, One Battle After Another (WINNER)

Clint Bentley and Greg Kwedar, Train Dreams

Guillermo Del Toro, Frankenstein

Park Chan-Wook, Lee Kyoung-Mi, Don McKellar, and Jahye Lee, No Other Choice (RUNNER-UP)

Will Tracy, Bugonia

Chloé Zhao and Maggie O’Farrell, Hamnet

Best Original Screenplay

Ryan Coogler, Sinners (WINNER)

Zach Cregger, Weapons

Jafar Panahi, It Was Just an Accident (RUNNER-UP)

Josh Safdie and Ronald Bronstein, Marty Supreme

Eskil Vogt and Joachim Trier, Sentimental Value

Best Score

Alexandre Desplat, Frankenstein

Ludwig Göransson, Sinners (WINNER)

Jonny Greenwood, One Battle After Another (RUNNER-UP)

Daniel Lopatin, Marty Supreme

Max Richter, Hamnet

Best Documentary

Cover-Up (RUNNER-UP)

Orwell: 2+2=5

The Perfect Neighbor

Predators (WINNER)

Seeds

Best Foreign Language Film

It Was Just an Accident (WINNER)

No Other Choice (RUNNER-UP)

The Secret Agent

Sentimental Value

Sirât

Best Animated Film

Arco

The Bad Guys 2

Elio

KPop Demon Hunters (RUNNER-UP)

Little Amélie or the Character of Rain (WINNER)

Predator: Killer of Killers

Zootopia 2

Frank Gabrenya Award for Best Comedy

The Baltimorons (RUNNER-UP)

Friendship

The Naked Gun

One of Them Days (WINNER)

Splitsville

Best Overlooked Film

The Ballad of Wallis Island

The Baltimorons

The Mastermind (RUNNER-UP)

Peter Hujar’s Day

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere

Warfare (WINNER)